Commentary on John 18:1—19:42

“Good Friday” was not “good” that afternoon in Jerusalem.

The series of events that ensue—within these two lectionary chapters (John 18-19)—bring closure to Jesus’ earthly mission. Judas’ betrayal—for which the fourth Gospel prepares readers (John 6:70-71; 12:4; 13:2, 26-27)—reaches its fulfillment. The arrest scene is followed by a series of trials for Jesus (18:19-24; 18:28-19:16) and less formal confrontations for Peter (18:15-18; 18:25-27). The narrative structure intersperses Peter’s “trial” with Jesus’ own, forcing a comparison. The repeated denials of Peter save his life. The truth-telling of Jesus causes him to lose his. The longest trial will be the one in front of Pilate and Jesus’s fate will eventually be determined.

The final scenes, after the arrest, draw our attention:

The narrative slows down as Jesus comes in front of Pilate (18:28-19:16). The fourth Gospel records a series of questions from Pilate but none from Caiaphas, the high priest, in a private meeting. As Pilate begins his (first round of) questioning, he goes right to the heart of the matter, “Are you Israel’s ‘king’?” (18:33)—a question for which the Gospel of John has prepared the reader from the beginning with Nathaniel’s opening confession (unique among the Gospels!): “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” (1:49; see also 12:13-15). Nevertheless, Jesus’ response—“my kingdom is not of this world”—implies a different kind of strategy for its influence and success (and, a different kind of battle); otherwise, this “king” idea would be a problem for Pilate (18:36).

Pilate’s questions move the trial along: “Are you the king of the Jews?” (18:33) “What is truth?” (18:38) “Where are you from?” (19:9) “Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?” (19:10)

Although Pilate did not find Jesus guilty according to this Gospel (18:38; 19:4, 6; 19:12), Pilate still had him beaten (19:1) and ridiculed (19:2-3). Usually, the Empire uses violence against its prophets. The most significant charge was that Jesus “claimed to be the Son of God” (19:7; see also 10:30, 33). The NRSV’s “claimed to be” is an attempt to translate the Greek text’s more literal “he made himself” (Greek heauton epoiēsen), which suggests that the religious leaders charged Jesus with acting in such a way as if he were God’s Son. After this charge, Pilate ends his questioning, performs his duty, and hands Jesus over for crucifixion (19:16).

Reading between the lines of the fourth Gospel, Pilate was just as responsible for Jesus’ death as the Jewish leadership. Jesus’ words (19:11) suggest as much. Pilate had the authority of Rome to carry out his own judgment. His sympathies aside, no one forced his hand even though the religious leadership disagreed with his initial desires. Concern over the intention of the inscription is unique to this Gospel (19:20-22). Pilate’s inscription occurs in multiple languages testifying to the multilingual (if not also multicultural) environment in the land of Jerusalem: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. The multilingual marker may also attest to John’s first-century audience in a region far removed from the confines of Jerusalem and to this Gospel’s attempt to depict “Jerusalem” as the epicenter of the world.

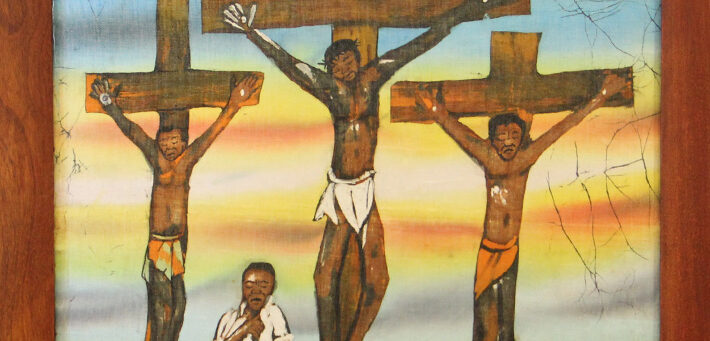

Generally absent from the crucifixion scenes in the canonical Gospels were descriptions of the brutality that occurred at these public events. The Gospel writers collectively omit the exposure of blood that would have been inevitable. Instead, they focus their depictions more on the public shame this event incurred, especially on the families and friends of the crucified. Along these lines, John offers the character Peter and his denial of any association with the soon-to-be-condemned as an example of Jesus’ isolation. On the other hand, striking is the presence of Mary (Jesus’ mother) in John’s portrayal, whose attendance makes the death seem less shameful.

In addition to Mary, the fourth Gospel mentions the presence of other women at the crucifixion scene. Only Mary Magdalene is explicitly mentioned in other Gospels as well. Commentaries debate whether the references to “Mary the mother of James and Joses” (Mark 15:40//Matthew 27:56) refers to Jesus’ mother. John’s Gospel is explicit!

The naming of his mother introduces one more scene in which the beloved disciple is distinguished from other disciples (see also 13:23-25; 20:2-10; 21:20-23). Here, Jesus places his mother into the intimate care of this disciple, not into Peter’s care (19:26-27). All canonical Gospels mention the presence of women in attendance at this crucifixion scene. Only the Gospel of John mentions the company of a single disciple.

Finally, the lectionary passage concludes with the burial of Jesus (19:38-42). Neither Peter nor the beloved disciple appear in this final scene before the resurrection (see 20:2). Rather, two minor characters within the narrative come to bury Jesus. Joseph was a “secret” follower of Jesus (19:38). Apparently, his secrecy was preserved since the fourth Gospel introduces him for the first time here. Nicodemus, on the other hand, made an earlier appearance in the narrative. In John 3, this leader among the Pharisees questions Jesus on his teaching and purpose. Although John’s Gospel did not portray Nicodemus’ final reaction in the earlier discussion, his presence here to assist Joseph implies that he, too, may have become a secret disciple. These two Pharisees oppose the Jerusalem priestly establishment’s opposition to Jesus of Nazareth.

A description of the “burial custom of the Jews” may suggest a non-Jewish audience for the Gospel of John (19:40). The narrative also repeats the timing of the death on the Day of Preparation (19:14, 31, 42), which signifies that Jesus’ death occurred before the Jewish Passover has been eaten, linking the sacrifice to the period of preparation when the lambs are slaughtered. The fourth Gospel’s description stands in contrast to the Synoptic tradition, in which Jesus’ crucifixion occurred after the Passover meal.

On this “Good Friday,” the fourth Gospel would have us see the inevitability of Jesus’ death. Jesus’ response to Pilate highlights the theological claims of the Johannine narrative: “You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above” (19:11). The various elements of these scenes that fulfilled the Scriptures of old—casting lots for his clothes (19:24), his thirst (19:28), unbroken bones (19:36), pierced side (19:37)—also testify to the inevitability of this death on a cross. But crucifixion was also Rome’s form of execution. Jesus died at the hands of the Roman state. At the original “good Friday,” the Empire won. But how we tell the story matters. Pilate had a choice but chose to appeal to the religious establishment. The Jewish leadership had a choice but choose to call for the death of one due to theological difference. We have a choice: what will we do this “Good Friday” season?

April 15, 2022