Commentary on John 19:31-42

As I write this, we’re approaching the 3rd anniversary of the death of Aaron, my first-born. That death, just before his 39th birthday, came from senseless violence. In those terrible days it was important for us to care for Aaron with some level of dignity and love, all the way to the end. So a friend and I drove behind the hearse as it made its way from the coroner’s office to the place of cremation. We accompanied Aaron as we could, in a largely silent vigil. Later, the family gathered around the chosen burial spot. With prayers of grief and hope we poured his ashes back to the earth from which they had come. We moved through those days, I think, with love and dignity, but with deep pain and anger as well. Our experience is hardly unique. Death intrudes with terrible regularity.

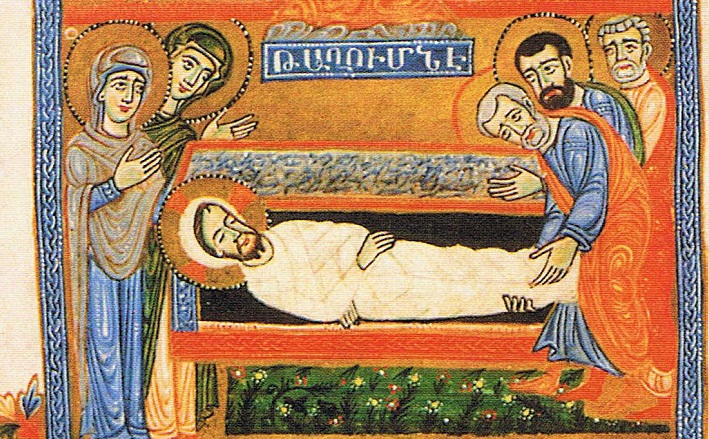

John’s account of getting Jesus from the cross into the tomb moves with love and dignity, even while being honest about the brutality of this death. In this journey, we see just how deeply the incarnation goes. I’ll say more about that later.

Rome had no problem leaving bodies of those executed on the cross to decay and be picked apart by animals. Such shock and degradation were part of the point of crucifying enemies of the state. But even an official like Pilate knew that at times relative peace could be purchased with a bit of concession. The ancient Jewish historian Josephus notes regarding the piety of Jews that “they took down those who were condemned and crucified, and buried them before the going down of the sun” (War 4.317). Thus “the Jews” (here understood as the Jewish leadership) ask for the deaths to be hastened by breaking the legs of those being crucified, and Pilate agrees.

The comment that Jesus has already died by this point is a reminder of John’s claim that Jesus willingly gave his life (10:18). The piercing of Jesus’ side may have been to test or to ensure that he was truly dead, but the result of that spear thrust obviously holds great significance for the writer of John (and for the foundational witness who steps out from behind the narrative at this point, probably the same one known as the Beloved Disciple). While the blood and water have often been explained in medical terms, this is hardly the significance that the Witness finds here, “so that you also may believe.” If we have been careful readers of John, we have already heard that blood (6:53-56) and water (4:10, 7:37-38) have been used to point to Jesus as the source of life. This final violence against Jesus becomes an image declaring that life flows out from Jesus’ death.1 So, it is not out of line to connect the blood and water with Eucharist and Baptism. If the preacher makes this move, it would be important to stress that these things are life-giving because the Jesus who gave his life on the cross is present in them, still giving his life to us.

It is perhaps the 18th century Moravians who explored the meaning of this scene the most profoundly and vividly. Drawing on medieval piety, they developed a deep (and sometimes shocking to others) devotion to the wounds of Christ, and especially to this side wound. In this piety, the wound on Jesus’ side was praised as the place opened to Jesus’ own heart. As such, it is the opening from which the church is birthed. We continue to live within the side wound of Christ. Small cards one could carry in a pocket were produced, with images of the faithful carrier residing within the open wound of Jesus’ side. Though such language and imagery may be uncomfortably graphic, the claims they were making are not that far from John’s point: grace and life flow from Jesus’ death. This is love, and it is in that love that we remain.

This text focuses on the reality of Jesus’ death. Bodies must be dealt with, they must be moved and prepared and buried. It is done here with dignity thanks to Joseph, and thanks to Nicodemus with an extravagance (fit for “the king of the Jews”) born from love and respect. There is no need for the women to return to the tomb later to complete the burial tasks. The body has already been cared for with dignity and love. When Mary comes to the tomb on Sunday morning, it is not because there is anything else that she can do for him. No one in this story has any reason to think that this is anything but the end of Jesus.

We are left to ponder the beauty and the pain of the incarnation. The Word became flesh – flesh that could be crucified, that could be pierced, that now must be wrapped with spices to cover the stench of decay and placed in a tomb. It is such flesh that can, ironically, fully reveal the glorious love and life of God.

In his death, Jesus gave up what human beings hold most dear—life—and he gave it up because he chose to do so in love. Jesus lays down his life in love for those whom he loves, and the meaning of both ‘life’ and ‘love’ are redefined … Love, love unto death, becomes the only true source of life. It is, indeed, pure gift—not required of him, but offered by him, so that we may understand the full extent of God’s love for the world.2

This is love “to the end” (13:1). It is this love of Jesus to which all his followers are called: to give to the end without calculation or restraint. Until that day when such love is perfected in us, we are called back to this scene, again and again, to be shaped by it once more.

Notes

- Gail R. O’Day, “The Gospel of John,” in The New Interpreter’s Volume IX (Nashville: Abingdon, 1995), 834.

- O’Day, 837.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Jesus our Passover Lamb,

We give thanks for the unswerving love you showed in your death and burial. Forgive and strengthen us so that we can rise with you, restored by your grace. Amen.

HYMNS

Ah, holy Jesus ELW 349, H82 158, UMH 289, NCH 218

Were you there ELW 353, UMH 288, H82 172, NCH 229

CHORAL

Were you there, Richard Proulx

April 15, 2022