Commentary on Psalm 22

St. Athanasius once observed: “Most of Scripture speaks to us; the Psalms speak for us.” Indeed, no texts of Scripture, perhaps in all of world literature, speak so directly and frankly to the uncensored and often painful rawness and realities of life as do the Psalms. That is, at least, if we will allow them to do so.

If we are honest with ourselves, we will realize that, at least as often as not, we live and exert considerable energy and preoccupation in the midst of what Walter Brueggemann calls “deep discontinuities.”1 On occasion, life feels oriented and perhaps mostly free from threat or trouble. But for most, such a (perceived) reality is the exception, rather than the rule.2

The subject matter of the Psalter testifies starkly to this imbalance. There are certainly psalms that affirm life as symmetrical and well-proportioned. However, it is a life-perspective that Brueggemann (and others) identify as “minimal” and a “minor theme” in the Psalter.3 Instead, the prevalence of the lament identifies the disoriented life as that which overwhelmingly gives rise to the speaking of the psalms.

Over one-third of the Psalms are laments, with even more containing a lament motif within a larger form structure. Unfortunately, typical worship and proclamation tend to grievously underutilize this trove of life-candor. There are 45 psalms that do not appear in the Revised Common Lectionary (for Sundays and high festival days); 30 of those un-included psalms are laments. The number of excluded lament psalms rises higher if we note the laments that appear as “alternates” (which are rarely used) or only as options for semi-continuous readings. If we narrow our survey to the time outside the Lenten season, then the use of the lament in our psalmody grows even more paltry.4

How can the Psalms speak for us if we underutilize the most prevalent genre of the Psalter, which speaks to what may be the most pervasive and shared of human experiences? The foregoing illustrates why the opportunity to read in its entirety and proclaim Psalm 22 is such a precious one, particularly at such a pivotal time in our world and faith journey.

The form of a lament contributes to its expressive power. With variations, laments will generally include the following elements, usually in the following order: complaint, confession of trust, request for help, praise. Psalm 22 begins with a particularly sharp complaint—perhaps the most memorable in all of Scripture: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”5 The suppliant goes on to ask why God is so distant and, in verse 2, in rather accusatory fashion, chastises God for failing to answer in the day and in the night.

Only the psalms of lament give such bold voice to feelings of fear, anxiety, and abandonment. If we largely fill our worship with expressions of the “happy-clappy” variety, these feelings experienced by virtually all in the pews will scarcely be addressed in the very place where they, more than anywhere else, should be, and thus will only deepen.

Questions regarding the value and genuineness of the gathered community are likely to follow, often culminating in distancing from an atmosphere that is so tone-deaf to the experiences of real life. Uncomfortably wearing the mask of a manufactured smile, and feeling the need to do so, is never healthy or healing, particularly in the church.

No such masks are purveyed or allowed by the lament psalms, however. Psalm 22 continues to explore and express the depths of human suffering. The suppliant confesses feeling only as a worm, not even a human, in verse 6, a self-perception exacerbated by the scorning, despising, and mocking of those around.6 Even God is the subject of a subtle swipe in verse 8!

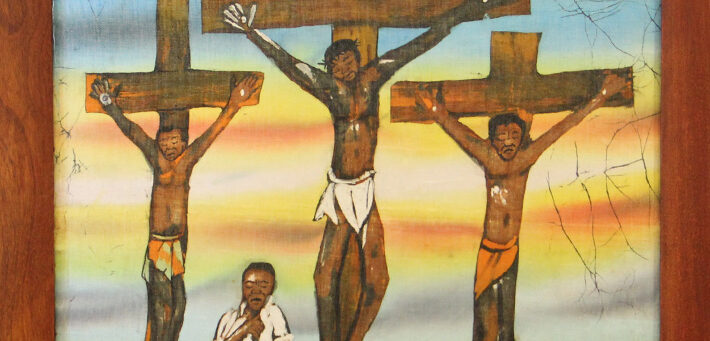

The imagery of verses 11–18 is particularly evocative: the encircling of bulls and wild dogs, feelings of being poured out like water, bones feeling out of joint, a heart as wax melting in the chest, a mouth as dry as a piece of broken pottery to which the parched tongue sticks. It is no wonder Jesus himself resonated with this psalm as he gasped for air upon the cross before a mocking crowd. Such, however, is precisely why God took on flesh and journeyed to Jerusalem: to know firsthand the darkest depths into which human experience can plunge us and, further, to win victory for all over such depths.

It is for this reason that we should not shy away from engaging in such barbed dialogue with God as we find in Psalm 22. God, not only apparently but clearly, wants to know and be with us in all the depths of our humanity. If our piety prevents us from being blatantly honest and expressing even anger with God, then we have a perverted piety. Thus, the lament, and even the complaint therein, is far less an expression of doubt than one of faith.

The lament psalm is, furthermore, an act of faith in that it includes, in the midst of deeply painful cries, professions of trust. We find such professions here in verses 3–5, 9–10.

God is enthroned on the praises of Israel, praises generated by the trust and deliverance experienced by the ancestors, who cried to God and were not put to shame. On a more personal level, the suppliant confesses being taken from the womb and kept safe on the mother’s breast by God, who has continued to be God ever since! The confession of trust suggests that since God has acted for the good of the people, often in response to cries in the past, God can and most likely will continue to do so. And so, again, we have a statement of faith within the psalm of lament.7

Out of these perspectives of faith, the suppliant can make the move to petition God for intervention.8 Thus, we find addressed to God in verse 11, “Do not be far from me, for trouble is near and there is no one to help.” Verses 19–20 repeat the request for God to be not far away, adding petitions for God to “come quickly to my aid,” “deliver my soul,” and “save me.”

Because God has an openness to and desire for hearing our cries, and because God’s faithful action in the past suggests continued saving action now and in the future, these petitions rise to God in anticipation of there being a response—yet another expression of faith.

Thus follows what may be the most startling piece of the lament form, which occurs in and is a significant portion of almost every lament psalm: the expression of praise.9 In Psalm 22, the expression of praise comprises a full one-third of the text (verses 22–31). Not only does the suppliant pledge to tell of God’s name to brothers and sisters, and to praise God in the midst of the congregation, but also exhorts others to praise, glorify, and stand in awe of God.

The scope of the praise continues to expand in verse 26, with the declaration that “the poor shall eat and be satisfied,” and even further in verse 27, saying that “all the ends of the earth” and “all families of the nations” shall remember and turn to and worship the Lord.

But even more startling and expansive is what we find in verse 29: Those who would typically be excluded from any kind of activity, let alone praise of God—the dead, “all those who sleep in the earth”—will also be included in this laudatory chorus. Thus, “posterity” will serve the Lord (verse 30) so that God’s deliverance will be made known even to those yet unborn.

What a journey these 31 verses undertake and invite us into. Perhaps at this end of the Lenten journey, someone may hear the words of this psalm and breathe the relieving sigh of finally knowing that they are not alone in their experiences—that this ancient text and even the words of our Savior resonate and connect with the depths of their emotions.

Tragically, you may have limited opportunity to offer on Good Friday these words of life to many who desperately need them, because in much the same way as our calendar of readings dodges and avoids the laments of the Psalter, people of faith tend to skip from Palm Sunday over the darkness of Holy Week and straight to the brightness—dare I say “happy-clappiness”—of Easter Sunday. This is to say, perhaps your proclamation of Psalm 22 need not be restricted to Good Friday.10 It may need to be the departure point of your proclamation on Easter Sunday, for without Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, the tomb, occupied or vacant, is meaningless.

Notes

- Walter Brueggemann, Praying the Psalms: Engaging Scripture and the Life of the Spirit, 2nd ed. (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2007), 6.

- Accordingly, the director of Clinical Pastoral Education with whom I studied once commented that when we stand in the pulpit to preach, above all, we should see seated before us individuals who, most likely, are experiencing some kind of pain in their life—and it is that pain that we must address.

- Brueggemann, 2007, 3–4.

- I chose not to add to the length of the above introduction by also referencing the many times when the lectionary does include lament psalms but omits some of the verses that most poignantly indicate the pain of the suppliant.

- Citations are from the New Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

- How often has such a scenario resulted in the mental distress and even suicide of our young people who were left feeling they had no place in or means by which to express and have earnestly heard their deepest angsts and apprehensions?

- Anderson points out the crucial difference between a lament and a dirge. The lament expresses a measure of confidence that the situation can be remedied by the intervention of God, whereas a dirge grieves over a calamity that is perceived as irreversible. Bernard Anderson, Out of the Depths: The Psalms Speak for Us Today (Louisville: John Knox, 2000), 60.

- Note that we dare not perceive this move as an easy one resulting from a neatly linear process! There is clearly tension and inner struggle in this suppliant, evidenced by the vacillation from cry in verses 1–2, to trust in verses 3–5, to cry again in verses 6–8, to trust in verses 9–10, to cry yet again in verses 12–18.

- Psalm 88 is among a few rare exceptions in which the suppliant is in such a depth of darkness as to render the expression of any praise impossible.

- While I get and appreciate the theological cleverness of the designation “Good,” I wonder if we also inadvertently sugarcoat the darkness and tragedy of this day, which needs to be experienced on its own terms rather than as some kind of flavor-enhanced snack.

April 15, 2022