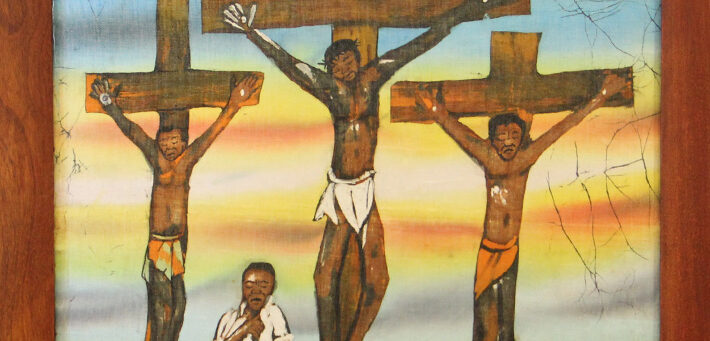

At Golgotha, the state is doing what the state does best: making an example. Rome crucifies in public not only to punish but to warn. The cross is a billboard of empire: This is what happens when you resist. This is what happens when you become disposable.

Jesus is not the only victim

Jesus is not alone on that hill. He is flanked by two others, labeled “criminals,” men reduced to their worst moments, their rap sheets, their charges. Their bodies hang in the open air as a lesson in submission. This is not just a religious scene, but a political one. Luke places Jesus inside a system of state violence that looks eerily familiar. Crucifixion is Rome’s version of mass incarceration, racialized policing, immigration detention, and public execution rolled into one. It is the machinery of control, and God steps in not as judge, not as governor, not as general, but as a condemned human being.

One of the crucified men joins the chorus of mockery by asking, “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” It is a desperate, bitter plea that sounds like the voice of every person who has been told deliverance is possible but has never seen it. It is the cry of those who have prayed and still been caged, deported, brutalized, forgotten. “If you are who you say you are, why are we still here?”

The other man interrupts: “Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? … We are getting what we deserve … but this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he turns toward Jesus, not in triumph, not in certainty, but in bare hope: “Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingdom.”

Remember me…

This is not a model confession. There is no doctrinal clarity, no sinner’s prayer. It is simply a man who knows he is dying, who knows the system is not built to save him, and who dares to believe that Jesus’s realm might be different from Rome’s. “Remember me.” In a world designed to erase him, he asks to be held in sacred memory.

Jesus answers with one of the most radical sentences in the Gospel: “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.” The declarative statement is futurist: not someday, not after rehabilitation, not once your record is cleared, but today! Jesus does not deny the man’s guilt. He does not minimize the harm he may have caused; however, he refuses the logic that says a person’s worst act is their truest nature. Empire says, You are what you did. Jesus says, You are who I remember you to be.

The promise of accompaniment

Paradise is not escape from the cross. It is presence on the cross. “With me.” Jesus does not promise a distant heaven; he promises companionship in the very place where the world has declared this man beyond hope. Liberation begins inside the cage. Grace shows up on death row. The kin-dom breaks open in a body marked for disposal.

For preachers, this text demands more than comfort. It demands truth-telling about the crosses of our own time. We live in a world where cages are normalized. Where over two million people are locked in prisons and jails. Where Black and brown bodies are policed as threats. Where immigrants are detained in “facilities” that function like warehouses for human beings. Where people are disappeared into systems that make suffering invisible. These are not anomalies. They are modern crucifixions, public warnings disguised as public safety.

Luke refuses to let us spiritualize the cross. Jesus is executed by the state alongside others the state has deemed dangerous. The gospel is not preached from a safe pulpit; it is spoken from a scaffold. And the first person to receive a promise of paradise is not a disciple, not a donor, not a religious leader, but a reviled man. This matters for congregations who believe faith is about being “good” and staying out of trouble. This text insists that Jesus’s closest companion in death is someone society has already thrown away. It unsettles any theology that equates righteousness with respectability.

An invitation to solidarity

For sympathetic congregations, this passage invites a deeper solidarity. It is not enough to feel compassion for “those people.” The cross collapses the distance between “us” and “them.” Jesus is not hovering above the criminalized; he is hanging among them. To follow him is to draw near to those the system keeps at arm’s length. For resistant congregations, wisdom is required. Some will hear talk of mass incarceration or detention and feel accused. The preacher’s task is not to shame, but to reveal. The question is not, Are we bad people? The question is, What kind of world crucifies people and calls it justice? This is not about partisan alignment. It is about gospel alignment.

The second criminal teaches us how to speak. He does not deny responsibility, but he does refuse despair. He names reality—“[we] are under the same sentence”—and still asks for mercy. Preaching from this text can honor complexity: Harm is real, accountability matters, and no system has the right to decide who is beyond redemption.

“Today you will be with me in paradise.” Jesus does not promise that the nails will disappear. He promises that the nails will not have the last word. That is a word for every mother waiting on a collect call. For every family torn apart by detention. For every community shaped by surveillance and suspicion. For every person who wonders if God has forgotten those behind bars or behind borders. The answer of the gospel is no, God has not forgotten. God is there. God is with us. God remembers.

Remembrance is active

This passage confirms that remembrance is not passive. It is active, insurgent, and world-shifting. If Jesus locates paradise in places of state violence, then the church cannot pretend those places are beyond our concern. The cross sends us into the world’s killing fields not as saviors but as witnesses, and not as judges but as companions.

Preaching this text is not about offering false hope. It is about telling the truth that God’s reign does not wait for perfect conditions. It erupts in unjust circumstances. It shows up in cells, camps, courtrooms, and streets. It is born wherever someone dares to say, “Remember me,” and someone else dares to answer, “You are not forgotten.”

This is what it means to preach the cross in a crucified world.

+ + +

This commentary is a piece of a larger series. The preaching series “Walking the Palm Sunday Path in Lent” can be helpful to congregations looking for instruction and motivation to participate in the Palm Sunday Path. That’s a movement calling Christians to put their faith into visible action, processing together during the afternoon of Palm Sunday (March 29, 2026) in state capitals and other cities across the United States. That and other scheduled events will allow believers to join their Christian kin in a hope-filled, visible proclamation of Jesus, who rejected the false glory of domination and retribution and declared that God has a better way, a path of love. You can learn more about the movement on the Palm Sunday Path’s soon-to-be-launched website; around the end of January, search online for “Palm Sunday 2026” or direct your browser to palmsunday2026.com.