Commentary on Matthew 26:14—27:66

“Then one of the twelve,” Matthew says, “who was called Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests” (26:14). These are the first words of our gospel, this Passion Sunday. One of the twelve! Jesus’s own disciple betrays him.

Matthew makes a few small changes to Mark (his source text for the Passion narrative) to paint a picture of sin.

- Matthew brings “one of the twelve” to the front of the sentence, emphasizing Judas’s close relationship to Jesus and thus the enormity of his betrayal.

- Matthew includes Judas’s question: “What will you give me to betray him to you?” All the synoptics and Acts tell us that Judas was paid for his betrayal. Mark says, “They promised to give him money” (14:11). Luke says, “They agreed to give him money” (22:5). But in Matthew, Judas actively seeks to sell his friend.

- The priests pay Judas thirty silver pieces: Only Matthew records the precise sum. Thirty silver shekels is the amount paid in Zechariah 11:12 for the shepherd of the flock doomed to slaughter. Later Matthew quotes Zechariah 11:12, applying it to Jesus (Matthew 27:9).

In Zechariah, the flock is governed by unscrupulous leaders, and so God sends a shepherd. “Be a shepherd of the flock doomed to slaughter. Those who buy them kill them and go unpunished, and those who sell them say, ‘Blessed be the Lord, for I have become rich,’ and their own shepherds have no pity on them” (Zechariah 11:4–5). The leaders are self-serving; they use their position and even their people for their own advantage, and the people suffer. It was true in the time of Zechariah, it is true in the time of Jesus, and it is true in our time now. So Matthew suggests, in thus folding past and present together in Jesus’s passion.

Judas’s sin is terrible in itself. But in hearing the echo of Zechariah in the blood-money, Matthew says something more. It is not only Judas in his self-interest who betrays Jesus. The leaders are part of this too, and it is the whole people who suffer. Sin is corporate, not just individual, and it affects the whole land (“and they shall devastate the earth,” Zechariah 11:6).

A greedy and self-serving leadership and a devastated earth: Ukraine comes to mind, and food rotting in warehouses in famine-stricken countries, and in rich America, poor families struggling to afford adequate food.

“And their own shepherds have no pity on them” (Zechariah 11:5).

Our gospel hears in Judas’s betrayal of Jesus not only our own individual sins of greed and self-interest but a corrupted leadership and a whole land’s suffering.

Jesus dies for each one of us. And he dies for a devastated world too. “Be a shepherd of the flock doomed to slaughter” (Zechariah 11:4). This is who Matthew sees that Jesus is.

Matthew also makes it clear that Jesus is this shepherd willingly.

When Judas comes to Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane and kisses him—kisses him!—in perfidious greeting, Jesus says to him, “Friend, do what you are here to do.” Then, Matthew says, they arrested Jesus. Jesus is in charge. He accepts the cup the Father is giving him—not lightly, indeed not without that night of agony in the garden—but he chooses this cup. He takes it from Judas, whom he has loved and chosen (“friend”), and he drinks it to the dregs.

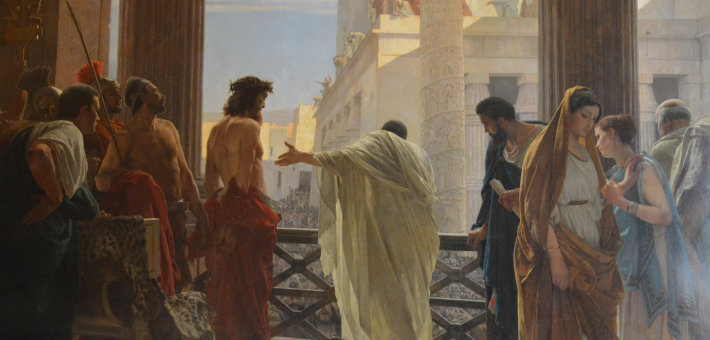

Judas betrays him, Peter denies him, and all the rest of his disciples—except for “many women,” who are also Jesus’s followers and who watch from afar (27:55)—run away. The priests and elders condemn and bind him, Pilate washes his hands of him, and the crowds who had just hailed Jesus as their king (“Hosanna to the Son of David!”) shout “Crucify him!” Even the bandits who are crucified with him taunt him.

In the face of human sin, Jesus is the shepherd who is true.

On the night he is betrayed, he acts out for his disciples what his Passion means.

Right after Judas goes to the chief priests and makes his deal, while he is seeking the right moment to betray Jesus, Jesus sits down at supper with his disciples—all of them, including Judas. He blesses the bread and breaks it and gives it to them. “Take, eat, this is my body.” He gives them the cup: “Drink this, all of you, for this is my blood” (26:27–28).

Surely only Judas can have any idea what Jesus is talking about—”my body, … my blood”; but Jesus is giving them, now, the words to understand what is going to happen. My body is going to be broken; my blood is going to be shed; this night it begins. And I give this death to you, Jesus says at the Last Supper, as blessing. “This is my blood of the covenant poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (26:28).

Jesus’s cross is the summation, the end-point, of sin, of all the self-interest and cruelty and corruption of the world, “all the innocent blood poured out upon the earth from Abel … to Zechariah” (Matthew 23:35). All the lands’ devastation is summed up in his dying (“there was darkness over the whole earth,” Matthew 27:45).

Jesus knows the cost of sin, and he takes it on his own back. He lifts it up to the Father on the cross and gives it back to us as forgiveness, God’s own covenant faithfulness.

So his death, which begins in the muck of human corruption, opens out into new life, a world devastated and remade.

In Matthew alone, as Jesus dies, there is an earthquake “and the rocks were split and the tombs were opened and many bodies of the holy ones who had fallen asleep were raised, and they came out of the tombs after his resurrection and came into the holy city and appeared to many” (27:51–53). What a strange scene!

But Matthew is wrapping the cross round with hope. There is real devastation for the land in Jesus’s innocent blood, as in all the innocent blood that has been poured out upon the earth. Darkness covers the land. The earth is shattered.

But this is not the end. By the grace of God there is more to this story than the capacity of human sin to destroy. Jesus’s death, in Matthew, is intertwined with resurrection.

Out of the shattered earth the people rise, bones knit together as God promised in Ezekiel 37, dry bones alive again. They rise at Jesus’s death. And after his resurrection—because the saving act is not complete in Jesus’s death alone, because death and resurrection are two movements in a single song of grace—after his resurrection the risen people of Israel come into the holy city and are seen by many. They are called “saints,” then and now, these people knit together and forgiven, given new life, in Jesus’s blood and his empty tomb.

Matthew takes us, in the Passion narrative, from Judas’s sin to a vision of a people who can be called holy. It happens, the gospel tells us, in Jesus, crucified and risen.

March 29, 2026