Commentary on Philippians 2:5-11

This passage represents one of the most important and influential christological hymns in the New Testament. For a good reason. Paul describes Christ as a kenotic figure, meaning that Christ derives strength through humility: By emptying himself, he is exalted; by obeying, he becomes Lord; and by becoming a servant, he is glorified. This hymn captures what may be the most significant contribution of Christian doctrine and practice to ideas of power and leadership. It is only through the humiliation of the crucifixion that Christ is glorified in the resurrection. But how does this view of “becoming God” relate to similar ideas in the Roman Empire?

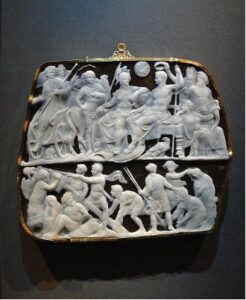

Let us look at a graphic example of Roman views of power, particularly as it pictures a Roman emperor becoming God.

The Gemma Augustea, a significant example of Roman art, is both a visual representation of imperial ideology and an artifact from the Augustan era.1 This cameo is generally dated to around 10 CE and depicts the apotheosis of Augustus, portraying him in divine form alongside personifications of victory and the gods. The Gemma is notable for its intricate depiction of figures that symbolize victory and divine authority, reinforcing Augustus’ status and the restoration of the Roman Republic’s glory following the civil wars.

The cameo features considerable astrological and political symbolism, particularly the Capricorn sign, which was associated with Augustus and illustrated his role as a reborn leader during the winter solstice—a time symbolically linked with renewal. Primarily, the figure of Augustus is at the center of the Gemma. He is shown in a godlike posture, indicating his posthumous deification, a theme prevalent in Augustan propaganda. The procession surrounding him features multiple deities and symbolic representations of virtues valued by the regime.

Among the figures in the cameo is Pax, personifying peace, which emphasizes Augustus’ dedication to establishing the Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, after years of civil conflict. Another important character is Victoria, the goddess of victory, who is shown crowning Augustus with a laurel wreath, symbolizing triumph and divine approval, reinforcing Augustus’ achievements as a military leader and peace-bringer.

Additionally, beside Augustus stands the figure of Rome, personified as a warrior goddess, emphasizing the strength and power of the Roman state under Augustus. This portrayal also signifies Augustus’ deep connection to Roman identity and the empire’s enduring legacy. At his feet, the eagle represents the god Jupiter. Two other historical figures accompany Augustus in the upper register. At the far left is Tiberius, Augustus’ immediate heir to the throne. To the right of Tiberius, standing in front of a chariot, the young Germanicus appears as another member of Augustus’ family entitled to inherit the throne. The message is clear: Augustus’ dynasty is entitled to the highest power.

Other characters include Oikoumene, who represents the civilized world by placing a crown on the emperor’s head. Oceanus, the embodiment of the seas, and Tellus Italiae, the mother earth goddess sitting with two children and a cornucopia symbolizing abundance, complete the scene.

These representations—like many others depicting the emperor wielding his power—serve not just as artistic expressions but also as political propaganda aimed at securing the emperor’s legacy and maintaining the empire’s peace and stability (the Pax Romana mentioned above).

However, notice that the depiction does not shy away from showing the brutal violence involved in the Pax. The lower register is explicit: Roman soldiers raise a trophy while degrading, humiliating, and capturing those who have been defeated. The Roman army would invade different territories, enslaving many of the newly conquered inhabitants and raping many women as they were sold into slavery.

The message is clear: Augustus is a godlike figure because he rules mercilessly over the violently conquered territories.

Katherine Shaner convincingly argues that Philippians 2:6b should be translated “He did not equate being God with rape and robbery.”2 If this is correct, Paul’s christological hymn offers a vivid reversal of imperial ideology, which equates “becoming God” with violence, robbery, and rape. Paul turns upside down, quite literally, the theology behind Gemma’s representation: Whereas the slaves appear in the lower ranks, evincing the emperor’s deification, in Philippians, deification happens through becoming a slave. The contrast could not be starker.

Furthermore, Philippians 2:8 emphasizes the extreme humiliation of the cross. Although the Gemma does not explicitly depict a cross, it’s easy to see how the imperial banner that soldiers plant on the newly conquered land resembles that instrument of torture—especially as humiliated captives stand beneath it and are dragged away, pulled by the hair. This reflects the defiance expressed in this hymn: Instead of placing Christ on the throne, Philippians identifies God with those same captives who will become slaves.

While the imperial depiction shows the oceans, earth, and heaven as part of an oppressive power structure, Philippians notices that “every knee should bow in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (2:10), not because Christ sits dominantly on the throne (like Augustus does), but because he has emptied himself to resemble the captives at the bottom of the hierarchy.

Notes

- The Gemma Augusåtea in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunsthistorisches_Museum.

- Katherine A. Shaner, “Seeing Rape and Robbery: ἁρπαγμαός and the Philippians Christ Hymn (Phil. 2:5–11)” Biblical Interpretation 25 (2017), 342–363.

March 29, 2026