Commentary on Isaiah 50:4-9a

This text in Second Isaiah (40–55) brings a human body into view. No gender, no name—only a body identified as an “I” subject. Such vagueness leaves the reader to identify only with the subject’s humanity. Here, meaning stays close to the human flesh—close to what the body both does and feels. Before the preacher pivots to theology, the passage offers sufficient bodily detail—tongue (verse 4), ear (verses 4–5), back (verse 6), cheeks (verse 6), beard, and face (verse 6)—to ground interpretation in the realm of the human. To remain with the text’s humanity does not lead to a superior human ideal but rather to human imperfection, frailty, and need.

A mentored tongue

The first body part to appear is the “I” subject’s tongue (verse 4). In prophetic literature, the production of human speech is attributed to the tongue. In the logic of the text, this is what humans do—they speak using their tongues. With the words they speak, their tongues ultimately give rise to a particular world. For the “I” subject, the world that exists points to speech that wounds.

Apart from the “I” subject’s body, other bodies are also present in the text—the exiles. The world they inhabit is not only the result of collective human labor but also of a tongue, a voice, a word, a discourse—hence an ideology. In essence, their displacement and captivity began as the spoken ideas of empire—ideas that denigrate and devalue others for no other reason than to conquer them.

In contrast, God has given the “I” subject a different tongue, one with teachings, or as rendered in the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition, “a trained tongue.” Such a tongue is generously given to the “I” subject, indicating a mentoring dynamic between God and the recipient. Certain forms of speech do not come naturally to the human tongue and therefore require careful instruction and timely training. As this line reveals, speech that heals is not automatic: “that I may know how to sustain the weary (yaʿēf) with a word.”

The term translated as “the weary” also appears in Isaiah 40:29, where it is paralleled with “the powerless” or, more literally, “bodies without strength.” In the context of Second Isaiah, these are the exiles held captive in a place where the empire “show[s] them no mercy” and “[makes its] yoke exceedingly heavy” (Isaiah 47:6). Ultimately, the words and corresponding actions of empire have made their bodies weary and powerless.

Imperial ideology creates an atmosphere that lands on the bodies of the conquered. Their devaluing wears down their personhood. Perhaps the preacher might ask: Who are the exiles or migrants in our midst made weary by wounding speech—words that dehumanize and denigrate?

Turning the body

To care for their weariness, a new discourse is required. For the “I” subject, it begins with a mentored tongue that, in turn, gives rise to a spoken word capable of sustaining bodies made weary by empire. This mentoring occurs “morning by morning,” awakening the ear of the “I” subject to listen “as those who are taught” (verse 4). A tongue that speaks a healing word is not taught in a single day, but over time—little by little—retraining the tongue to speak words of care rather than wounding words.

Healing speech that lifts those made weary by hateful words is, in many ways, the preacher’s task. How can the words preached from pulpits situated within places that devalue and dehumanize the Other be life-giving—and even empowering? How might communities of faith engage in a form of discourse mentorship in which words of healing and love shape the tongues of all their members?

Speaking life under threat

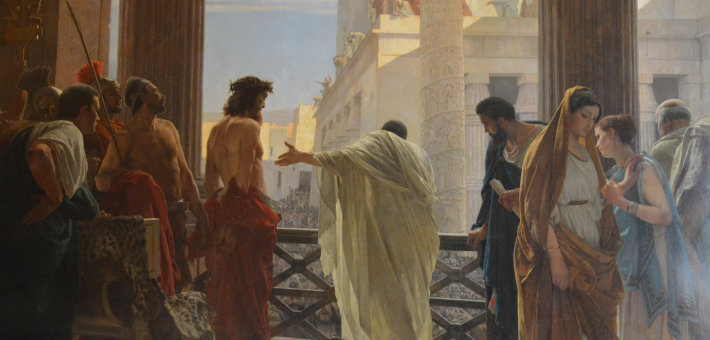

Tracing a movement from tongue to ear, the text turns the reader’s gaze to the back of the “I” subject. This part of the body suggests a turning motion that accompanies the mentoring of healing speech. A tongue that speaks healing to the hurting, in other words, requires a reorientation of the physical body toward a different speech source. To hear words of healing and then voice them, the body must turn in a new direction (verse 5). Here, that turning is away from the agents of empire—those whose way of being is not healing but harming. Yet such a turn carries bodily consequences: The body that turns away from hurtful speech risks being hurt by those in power who rely on it.

Following the mapping of the human body in the text, each identified part is tied to the production of life-giving speech and its consequences. First, there are the tongue and ear, mentored in such a way that they turn the whole body toward a discourse of healing. This embodied form of learning, however, stands in opposition to those in power producing wounding discourse.

In response, the body that speaks healing becomes the site of retaliatory violence. They target the back—the part signifying a turn to a different source of learning and, hence, speaking. They inflict pain on the cheeks—the part closest to the tongue. They spit at the face—the part closest to the ears. Their reaction is consistent with their adversarial way of being, speaking words of insult—that is, a shaming discourse (verse 6). In the end, the body parts that produce words of healing for the weary become targets for violent censorship.

In today’s world, educational spaces that mentor a discourse of life-giving speech for those wearied by greed and hate are likewise targeted for violent silencing. How will the body of the learner, the one formed by healing discourse, continue to speak when the very act of speaking life invites harm? The text offers this response: “The Lord God helps me; therefore I have not been disgraced” (verse 7).

March 29, 2026