Commentary on 1 Kings 17:8-16

The literary shifts that bring us to chapter 17 in the book of Kings make Elijah the central character of this narrative.

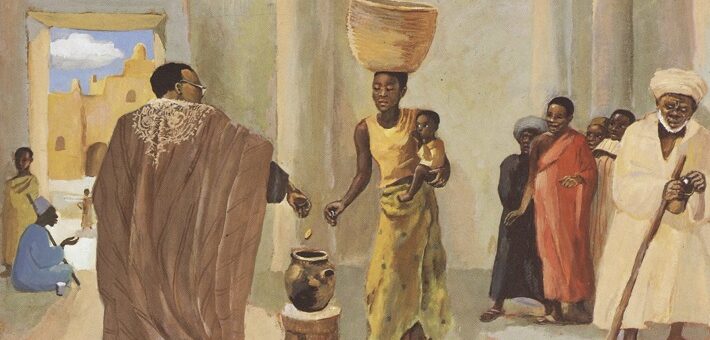

The chapter interrupts the flow of the royal narratives allowing Elijah to literarily and literally crash Ahab’s time in the sun. Despite this focus on Elijah, this lectionary passage offers more when considered from the perspective of the widow. Changing this perspective enables readers to view the widow not simply as a victim requiring charity and the miraculous intervention of the prophet, but rather as an actor in the story of her life and one surviving in the midst of difficult times.

Chapter 17 features three stories, each aimed at proving Elijah’s worth as a prophet and the one who will challenge the theopolitical system advocated by the northern Israelite monarchy. This theopolitical system embraced openness to Canaanite theologies that assigned control over nature to Baal and other gods as well as engaged in the political alliance created by the marriage of king Ahab to the Sidonian princess, Jezebel. The geographical markers and indications of fertility withheld and given in the chapter serve as polemics in the theopolitical fight. The contest appears variously as between Yahweh and Baal, as well as theological and cultural exclusivists and inclusivists. Elijah appears on the scene as the worthy antagonist to the presumptions followed by the monarchy. In this episode with the widow, he proves Yahweh as the only guarantor of fertility. This passage follows the first episode in vv. 1-7 where Elijah experiences the power of Yahweh to give and withhold rain, to direct him to sources of water, and to provide and withhold his food.

The widow appears in the midst of these overarching battles and antagonisms. Already a victim of economic circumstances, in this passage, she serves as a site upon which theological polemics can play out. The focus on the theological victories of Yahwism over the alternatives of Baalism overlooks the plight of the widow and her agency. Already placed at a social and economic disadvantage, the widow experiences further distress in the midst of a drought. That she has a young son who is dependent upon her tells us something about her proximate age. She is not old and feeble. Without a husband she has little means of support and no doubt the drought would have exacerbated her predicament. Readers need to remember that the widow lives in Sidon so that the usual social support prescribed by Deuteronmy 26:12 may not have been in force in Sidon. And whatever system of help that may exist in Sidon, the drought would have degraded the effectiveness of that system. Elijah meets the widow at perhaps her lowest level of resources. She is in the midst of preparing what would be the last meal that she could eat from the resources she has available.

The drought exaggerates the widow’s plight. The narrative invites readers to see the drought not simply as a natural event but an intentionally divine occurrence. One of the stakes in this narrative revolves around which deity controls nature. In this regard the drought appears as weapon in this divine cold war. Consequently, the widow can be seen as part of the collateral damage that occurs with wars. Indeed, readers should see in the widow the faces of those whose already compromised economic resources are made worse by events such as wars and misdistribution of resources. Natural events such as drought ought not to be singularly blamed for the fate of the widow. Rather, how societies organize themselves, as well as how they respond to the demands of their natural environments, make a difference in the lives of vulnerable populations. In this story Elijah appears insensitive to the widow’s situation. He seems selfish and callous (1 Kings 17:10-11). And his pious speech ignores the part theological antagonisms play in making things difficult for the widow and her son (vv. 13-14).

Although Elijah meets the widow at the near end of her resources, she has been actively engaging in her survival. The widow forages for fuel to cook something to eat. Having gathered enough sticks, she sets out to prepare that last meagre dish. Elijah interrupts her. Despite being the one in need, she responds to the demands of hospitality and brings water to Elijah (1 Kings 17:11). Readers receive no indication from where the meal and oil in her house come. That the woman has not remained passive or simply dependent upon others is clear from the text. Her seemingly fatalistic admission in v. 12 appears more as the statement of someone who has been fighting the battle for survival and recognizes the power of the enemy rather than someone who has had no fight in her. Readers may never know whether the agency of the widow would have led her to share her food with Elijah, because he never allows her the opportunity to extend her hospitality that far. Instead, readers only get to see the widow placing Elijah’s need above hers and those of her son as a test of her faith in the god that Elijah serves. The delicacies of theology mean little when caught between survival and death. The widow of course follows Elijah’s lead and the continuous flow of food confirms his claim in the superiority of his god. The question of belief never arises in this passage as it pertains to the widow because the widow as a foreigner is merely a pawn in the theopolitical war. For this passage, the belief of the readers in the supremacy of Yahweh over Baal serves as the critical concern and therefore their belief forms the central concern of the passage. Readers, particularly ancient ones who would have understood the theopolitical stakes, could view Elijah as the representative of the deity that guarantees fertility. This chapter, in that regard, forms an ideal staging ground for the combative events of the following chapters.

Easily viewed as a miracle story, this passage does not set out to be simply a miracle story. The passage draws readers into a conflict and presses them to take sides. In so doing, the widow functions as a pawn in that fight. To view the passage as only a miracle story also overlooks the widow. Her foreignness in every way sets the stage for the unlikely display of divine power. In this framing, Elijah emerges as the brilliant miracle worker deserving of awe and the widow correspondingly recesses into the background. These frames for the story not only erase the widow, they distract attention from the social and economic disparities that lie at the heart of the text. The claim of special attention to widows, orphans, and sojourners does not always result in they becoming central or strong characters in the Bible. Reading this passage from the perspective of the widow can help in recentering these characters — the socially and economically vulnerable — and making them more than simply the objects of charity. This widow fights valiantly to offer life to herself and her son for as long as she is able to do so.

The conclusion of this episode could be written and translated in different ways. The Hebrew indicates that the meal jar was not exhausted and neither was the vat of oil. The verbs used in the Hebrew appear to describe an ordinary event until it is clear that they are pointing to an inexhaustible flow of resources. The NRSV translation evokes a sense of wonder by using the verb “fail” to talk about the oil. The details of what took place remain unclear leaving open the possibility of talking about this as miraculous. Attempting to prove or disprove how this unending supply of goods take place goes beyond any reasonable concern for the value of this passage. Instead, seeing how a widow responds, not anticipating something miraculous that would save her life, with hospitality, openness, and readiness to share with Elijah should raise her higher in readers’ attention. The last verse calls the reader back to the opening verse of the passage. In 1 Kings 17:9 Elijah undertakes the journey to Sidon in anticipation of meeting the woman divinely predisposed to feeding him. At this point in the narrative, Elijah has also exhausted his resources for food. In fact, the widow appears to have more than he does. Her obedient response to be liberal with her little resources contrasts markedly with the divine withholding of rain and the suppression of fertility. Her openness to giving away her little food grants her greater agency than Elijah whose only task lies in going in search of food that he is guaranteed will be there. In the grand scheme of things, the widow casts a searing light upon the other characters in the passage. Reading her will press communities to examine what they ask the vulnerable in their midst to do in service of particular ideologies or in the maintenance of the status quo of charity. Reading her will call into question presumptions of the inabilities of the vulnerable and challenge communities to more meaningful engagement with various members of the human community.

November 8, 2015