Commentary on Psalm 146

Psalm 146 is structurally simple, yet theologically profound.

Its genre is one of praise and it is part of the crescendo ending of the psalter. The psalm begins and ends with the same “Praise the LORD” or “Hallelujah,” providing an envelope called an “inclusio.” Inside this envelope are two doxologies surrounding two stanzas, giving a symmetrical shape to this prayer.

The first doxology is personal and enduring and better translated as “I will praise God with my whole self” instead of the standard “soul.” “Soul” provides a meaning of an inner devotion or that the “soul” is something other than the self. The prayer calls for us to involve our whole selves in the life-long act of praise to the LORD. It is a call to action.

In our world, praise has been difficult recently. News from our country and across the world is filled with religious wars, murder, slaughter of innocents, and massive refugee migrations. It is hard to “praise God with my whole self.” Yet, in most of the history of ancient Israel, their situation was similar. Here is the first lesson of this psalm. Praise of God is sometimes an act of discipline. Under the circumstances of war and destruction, praise is not the result of external happiness, but stubborn belief in the face of evidence to the contrary. Indeed praise is defiance of worldly powers. It shouts that despite the situation around me, God is still worthy of praise. The ancients knew that life-long praise can change the world by transforming and empowering individuals. Crying to God is an important cathartic, but praise can change our outlook. Praise provides power when we feel powerless.

The first stanza (Psalm 146:3-4) changes direction abruptly. The move from praise to “do not trust” is a harsh one. But the stanza is a reminder. We are not to place our trust in humans, even human leaders. Notice, the psalm makes no distinction as to the nature of the leader. The leader may be good or bad, his or her merits are not the point, rather their human condition is. Leaders, like all humans, will come and then go to the ground and all of their plans will go with them. Like the old sage, Qohelet, we are reminded of the fleeting nature of the humanity. Human plans are small and transitory. Life-long praise and trust are reserved for the LORD alone.

The next stanza (verses 5-9) returns focus to the one praying. It opens with the Hebrew ‘asher, often translated as “happy.” In the context of a praise psalm, this definition works as long as we remember it is not a passing or superficial happiness, but a deep abiding “contentment” with the human condition and one’s God. It is life as it is supposed to be and it is achieved by having God as one’s “help” and “hope.” This is the contrast to the stanza above. If happiness is elusive, contentment may even be more difficult. We live in a world where contentment is countercultural. Much of our economy is based on consumerism and a capital economy fueled by the desire to acquire more and more things. Yet true contentment is centered in God, not human made items and plans.

And what a God we serve! God is Creator of the heavens, the earth, and the seas (v 6). God is the Sustainer who keeps faith (in Hebrew the word also means “truth” and “firmness”) forever (v 6), and God is the Redeemer who rescues those who are oppressed and hungry (v 7). These attributes serve two purposes. The first is to remind us why God is to be praised for our whole lives and the other is to provide additional contrast to those human rulers. God and God alone is the reason for our creation and continued existence. The psalm adds five ways of the LORD, all centered on God’s justice (vv 8-9a). One can imagine that as each line is read or sung, it is followed by a resounding response of praise. The psalm concludes a final doxology celebrating God’s enduring presence in the world and a final shout of “Hallelujah.”

For preaching, this psalm offers an oasis; a cool, comfortable place where we can put aside the world and praise God for who God is. The prayer is designed to combat narcissism and consumerism. It is to lift our eyes above our day-to-day troubles and into the infinite realm of God. In a world gone crazy, this moment of perspective has been a shelter for centuries. As African-American churches have experienced threats over the summer, the people gathered to sing praises to God and these praises provide strength and sustenance. This is a tradition reaching back to slavery. Sunday morning praise allowed these folks to become fully human for a moment. What the ancient Israelites knew about the power of praise has and is being lived out in communities overshadowed by racist threats. Troubles still exist, but the worshippers are now better equipped to go forward. Praise, it seems, is the very definition of Sabbath rest in God.

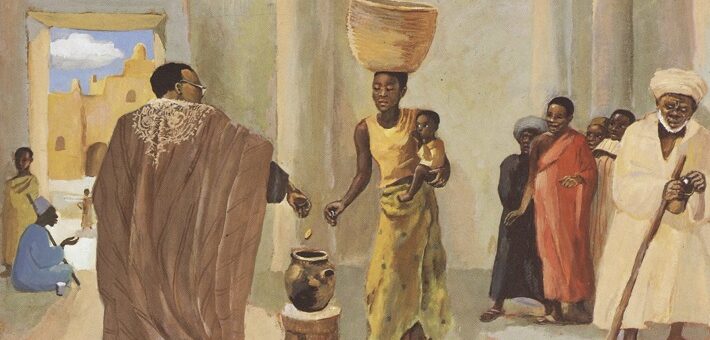

Another preaching possibility is to use the contrasts in the psalms and parallel them with the contrasts in the Gospel lesson. This is a wisdom psalm and contrast is part of its structure. The contrast is between human plans and their inherent frailty juxtaposed with God’s justice plans and God’s eternity. The Mark text is a great example of human plans to impress others and God juxtaposed with the widow and her small mite. The summary of that story could easily be “the LORD upholds the widow and the orphan, but the way of the wicked he bends (verse 9).”

November 8, 2015