Commentary on Psalm 104:24-34, 35b

It is no new observation to say that the lectionary cherry-picks. If verses are left out of a chapter, the first thing you should do is go examine them.

Some of the best Pentecost material from Psalm 104 is left on the editorial room floor here. “Fire and flame” are God’s ministers, the “wings of the wind” are what God rides upon (104:3-4). From verse 15, the wine God makes to gladden the human heart and the oil to make the face shine sing of eucharist and anointing—both actions that require the calling upon of the Holy Spirit.

The entire psalm sings the goodness of creation, made by and for and in the Holy Spirit. The one bit left out of our lection—“let sinners be consumed from the earth, and let the wicked be no more”—is no exception. Psalm 104 depicts creation as it is meant to be, as it one day will be in God’s good time.

It was humanity’s fall that led to the fall of all the cosmos. So God the Spirit will one day judge sinful human beings and repair the world we have ruined. The left out bits preach the gospel. The rejected stone has become the head of the corner (Psalm 118:22). No need to share that with them—no congregation has ever been edified by preachers lamenting the lectionary any more than a toilet has gotten fixed by a plumber decrying her tools. But it’s important for the tool-bearer to know.

A sermon on this passage for Pentecost could focus on the Leviathan of verse 26. Here in British Columbia, people do strange things. They pay boats to ride up as close as possible to whales so they can take pictures. Aboriginal peoples on this continent did something more brave: they rode up close to such creatures in canoes a few inches above the waterline to hunt them. Perhaps ancient Israelites had it right—stay away. The sea is a fearful place. People who go that way never come back. Israel’s neighbors were often seafaring peoples—the Phoenicians and the Greeks and others had tales of conquering mariners. Israel did most of its conquering on land, thank you very much.

In the ancient world, such great sea beasts were more often a source of fear than of wonder. In Psalm 91 or Job 41 or the book of Jonah, the great fish is a sign of creation disordered, frightful, destruction-wielding. But here, Leviathan “sports” (104:26). It plays. Perhaps the psalmist has seen a whale breaching, though scientists still cannot be sure what purpose this action accomplishes (it could be play, or it could be seeking relief from enormous intestinal parasites!). A creature that otherwise devours and shows God’s power for destruction, here shows God’s creative power, God’s control over what is otherwise death-dealing. Maybe Leviathan is on a leash like a house pet.

In Psalm 104, the entire zoo worships. The word “hallelujah” appears here in the Bible for the first time—and it is on the lips of creation far beyond the merely human. Environmentalists often complain that Christianity has caused our ecological crisis, with some evidence. But Wendell Berry responds with the author’s lament—those who critique might first read the book. The Bible is an outdoor book, Berry says. We might go a step further and say that the Bible’s view of creation is as the setting for the jewel of redemption. In Psalm 104, the creatures know this full well. All look to God for food in season. God provides, they are filled; God hides his face, they are dismayed. More interestingly for pneumatological reasons, when God hides the divine face and takes away creatures’ breath, they die, and return to the dust.

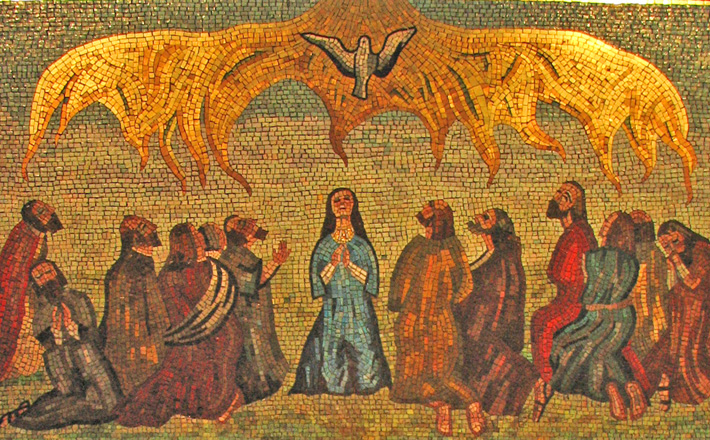

Breath. Ruah, in Hebrew. Pneuma, in Greek. God is breath, spirit, life. At the beginning, God’s Spirit hovers over chaos, breathes life into dirt, and humanity becomes a thing. The psalm says when God sends forth the Spirit, creatures are renewed and all the land is filled with life once more. Barbara Brown Taylor speaks somewhere of seeing Desmond Tutu perform a baptism. He lifted the lid to the font … and breathed over the water. And the church saw the breath of God blowing life over the chaotic waters in the first place, blowing over the waters of salvation, bringing new life where there was only watery death. The last 100 years or so in the church have seen the rise of Pentecostalism, growing from a non-existent non-thing to a stream of the church nearly one billion strong now. God is reminding us that God is Holy Spirit, powerful, fiery, teaching new languages, blowing us out in mission to the ends of the earth. Psalm 104 reconnects this powerful movement of Pentecost, both in Jerusalem in 33 CE and in Los Angeles in 1906, to creation. The Holy Spirit is not just known in tongues of fire, though of course he is. The Holy Spirit is also known in every particle of creation, everything that breathes, everything that sports, everything that lives. One of the dangers of seeing creation as godless is that then you can use it up, exploit it, and be done with it. God’s word won’t let you do that. God lives in creation, loves it, gives life to it, gathers it up to dust to give yet more life to it. God will not be God without creation. That is why God is planning to renew all things (104:30).

Another fine image for the Spirit’s person and work here is in the smoking mountains (104:32). My Cree colleague at Vancouver School of Theology, Ray Aldred, points out that native peoples hardly ever worship without setting something on fire. So too, the Holy Spirit. Just a touch of the Spirit’s finger and the mountains quake and burst forth in flame. Some churches signify the Spirit’s presence with the burning of incense. Others use sage. Most at least light a candle. Some, Orthodox especially, build with golden domes, meant to flash fire far and wide. All are lit aflame by the God who is altogether fire. That fire burns and cauterizes. It also heals and gives new life.

Watch out. This fiery Spirit who cavorts with deadly creatures is coming, and is even already here.

May 31, 2020