Commentary on 1 Corinthians 12:3b-13

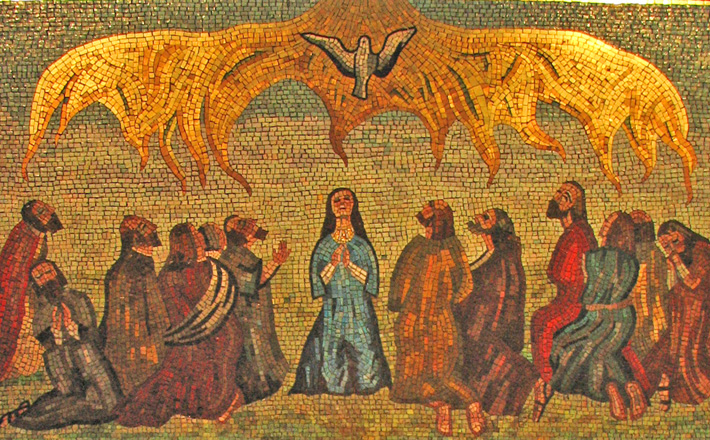

What does it look like to be people of Pentecost, to be those claimed by the Spirit?1

In the cultural buffet that is offered under the sign of “spirituality,” this passage from 1 Corinthians makes some important claims about the Spirit through which the church lives, and about the shape of faithful spirituality.

Paul’s discussion begins in verse 3 by insisting that the undeniable sign of the Spirit’s activity will be confession of Jesus as Lord. The Spirit brings faith itself, and specifically faith focused on Jesus as Lord. At this point, Martin Luther was deeply Pauline when he wrote in the Small Catechism, “I believe that by my own understanding or strength I cannot believe in Jesus Christ my Lord or come to him, but instead the Holy Spirit has called me through the gospel, enlightened me with his gifts … ”2

Paul connects the Spirit to Christ, so that the true manifestations of the Spirit are those which demonstrate that this is “the Spirit of Christ” (Romans 8:9; see also Galatians 4:6, “the Spirit of his Son”). The Spirit leads the believer to join in Jesus’ own prayer and cry out, “Abba, Father” (Romans 8:15, Galatians 4:6). Thus Christ himself becomes the measure by which genuine activity of the Spirit can be identified, and all who confess this faith are under the power of the Spirit.

This is a radically inclusive claim. As far as the Spirit is concerned, there will be no room for the categories that culture might use to divide the haves from the have-nots (“Jews or Greeks, slaves or free,” verse 13). By the very nature of faith as a divine gift, the Spirit has been and continues to be active in all who confess Jesus as Lord.

Paul indicates how to understand the Spirit’s activity in the church by his identification of the Spirit’s work through the believers as “gifts.” The root of this word points to the nature of these gifts: the gifts (“charismata”) are the result of God’s grace (“charis”). The gifts of the Spirit are the active, experienced instances of God’s grace at work in the church. All believers are given such gifts of the Spirit (notice “everyone” and “each” in 6b-7a).

To be gifted by the Spirit is not something that happens to some believers but not to others. Paul never gives us the impression that he expects some people in the church to be the ones who are ministering, and that there are others who are simply ministered to because they haven’t been given any of the Spirit’s gifts.

However, it may seem as though the gifts that Paul names here are uncomfortably absent from many of our congregations. While I rather regularly see evidence of wisdom and knowledge (verse 8) in the community where I worship, speaking in tongues and their interpretation has never happened there as far as I know. Healing certainly happens, but usually through the mediation of doctors, medicines, and therapy.

Miracles may happen, though spotting them usually means finding God hidden in what others would see as a “normal” event. So, where are the gifts of the Spirit? We might be more successful in spotting the spiritual gifts that Paul lists in Romans 12:6-8 — ministry, teaching, exhortation, generosity, leadership, and compassion.

In my experience, when (and if) we talk to people in our congregations about their spiritual gifts, we tend to focus on these sorts of characteristics and talents rather than on the flashier items mentioned in 1 Corinthians 12. That’s not necessarily wrong; we rightly thank God for the talents and abilities we have.

Yet it isn’t quite right to simply equate talents with “gifts of the Spirit” either; there is something more involved than simply talent. Paul’s central point about these gifts is made in verse 7, where he notes that these gifts are given to each for the good of the whole church. This allows room for us to rightly identify as gifts of the Spirit those talents that are informed by, summoned by, and “energized” (NRSV “activated”, verse 11) by the Spirit for the good of the church.

We are not talking about being “gifted” individuals who have the talents required to get ahead and earn a good salary or the admiration of others. Paul wants the Corinthians to adopt a new way of looking at spirituality by seeing these abilities as a means through which God is at work with grace and mercy for the whole community. It is that dynamic which transforms talents into gifts of the Spirit. When, by God’s grace and power, talents are reoriented away from us and our own interests and when they become vehicles for God’s love, they are truly the Spirit’s gifts to the church.

Believers are not simply individuals who are empowered and gifted by the Spirit. They are interconnected parts of a single body, and it is to this image that Paul turns near the end of our passage. Others in Paul’s culture used the image of the body to strengthen the hierarchy of society. Philosophers and politicians said that human society was like a body, which had to have a head that told everything else what to do. Of course, the elite rich get to be the head (or the stomach!), and the poor need to keep working as the hands and feet.

Paul overturns this common use of the body image. He questions any assumption that some members of the body are more important than any others. In the body of Christ, behavior will not be determined by concern for honor and status, but by what builds up the whole body, by interdependence, and by love. The work of the Spirit, correctly understood, will result in a unified body of Christ, not in competition or division, since we all receive life and growth from the same flowing baptismal grace (verse 13).

Notes:

- Commentary first published on this site on June 8, 2014.

- Book of Concord, ed. Robert Kolb & Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2000), 355.

May 31, 2020