Commentary on Revelation 1:4b-8

Jews mark the end of the yearly Torah cycle with the wonderful holiday of Simchat Torah, “Joy in the Torah.” They take the huge Torah scrolls out of the ark and dance with the scrolls. I wish the Christian lectionary’s end of the church year focused more on the joy of dancing with the scriptures‒‒rather than on kingship, dominion, triumphalism, and judgment.

At least three challenges confront liberation preachers today:

First, Christ the King Sunday’s recent and imperial origins, dating only to 1925. As Lucy Hogan describes, Pope Pius XI instituted this observance because “followers of Christ were being lured away by the increasing secularism of the world”.

Second, we preach in a time of fear and despair, when people’s experiences feel increasingly apocalyptic. One in three Americans have felt the direct effects of climate disasters this past year, while political tensions and the COVID pandemic rend our communities.

Third, the lectionary itself saturates people’s imaginations with doom and gloom for several Sundays in late November. Last week brought us Daniel and Mark 13; next week we will start Year C by reading from Luke’s apocalyptic discourse.

As preachers, our calling must be to counter all three of these challenges by offering a radical message of hope, not doom and gloom! Fortunately, Revelation offers the hope and joy in this week’s wonderful imagery.

Hope: the world is about to turn!

I recommend Rory Cooney’s joyful “Canticle of the Turning,” in the hymnal Evangelical Lutheran Worship #723, to proclaim the message of hope at the heart of Revelation. Revelation’s message is not that the world is about to end, but that the world is about to turn.1

My students love to sing the “Canticle of the Turning,” with its Irish tune and text from Mary’s Magnificat. Reminiscent of Simchat Torah’s dancing with the Torah scrolls, we can end the church year by dancing and singing the liberating message of hope in Revelation, in the heart of our scriptures: The world is about to turn!

Christ is King over against the Roman Empire and all kings of the earth

Revelation’s subversive political challenge, like Daniel’s, is unmistakable. Jesus is “the one ruling the kings of the earth” (1:5)‒‒a rule proclaimed already in the present tense.

John in effect says “no” to Roman propaganda’s hegemonic claims that Emperor Augustus’s reign had ushered in a new eschatological golden age of peace for the whole world. John also reclaims Roman political values of “glory” and “dominion” (1:6) for Jesus‒‒values claimed by Rome in its imperial propaganda, hymns, and celebrations.

When we say the creeds, we are in effect saying “I believe in God … and not in Caesar.”

Community

The purpose of Revelation’s apocalyptic story is to empower an alternative community as followers of the Lamb Jesus (Revelation 14:4), and to strengthen people’s witness to God’s reign of love and hope in the face of evil. The preacher’s job—whether preaching on Jesus’ apocalyptic discourses, on Daniel, or on Revelation—is to strengthen community and inspire that testimony.

Throughout the book, John continually shapes the Christian community as a countercultural community. God’s people are called a “kingdom of priests” (1:6; a theme that will recur in 5:10 and 20:6). John draws this imagery from the Exodus story in which God liberated Israel from Egypt to be a “priestly kingdom” (Exodus 19:6), and from Isaiah’s description of God’s people as priests in the return from exile in Babylon (Isaiah 61:6).

In the sixteenth century, reformer Martin Luther drew his doctrine of the priesthood of all the baptized from the proclamation of God’s people as a “kingdom of priests” (Revelation 1:6), similar to the “royal priesthood” of 1 Peter 2:5 and 2:9. Luther’s notion that “we are all priests” (Babylonian Captivity of the Churches) became a central tenet for Protestants.

John’s use of language and imagery subverts Roman imperial theology

Note John’s use of peculiar Greek grammar in 1:4. This is probably deliberate, suggests Allen Dwight Callahan. Literally translated, the greeting from God is “from He the Is and He the Was” (incorrectly using a nominative case following the preposition apo). John often defies grammatical rules in ways that would have sounded strange to Greek ears (see also Revelation 1:11, 13, 15; 2:13, 20; 3:12; 4:1; 8:9; 14:7, 19; 19:6, 20). English translations that smooth out his Greek may do John a disservice, since his use of non-standard Greek appears intentional. He may be calling attention to scriptural allusions, or more likely he may be subverting grammar rules of the dominant culture as a form of protest or resistance.2

Revelation’s imagery is evocative, not propositional

Apocalypses persuade not by logical proofs or arguments, but by creating a “world of vision,” as Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza argues. Some words that shape that world of vision in this text include:

“Witness” (1:5): Jesus is the faithful “witness,” introducing a term of crucial importance throughout the book. The Greek word “witness” (martys) can also mean “martyr.” John has a high view of the power of the community’s witness to change history—even saying we conquer Satan by our witness, in Revelation 12:11.

“Behold” is one of my favorite words in Revelation, idou in Greek, in Hebrew hinneh, translated in the NRSV as “see” or “look” —directing us to pause to see something important, usually something wonderful. I wish the NRSV had not done away with “behold”.

“Coming” (1:7) is present tense, suggesting a coming already underway. John switches freely among past, present, and future tenses throughout the book in a manner typical of the visionary language of apocalypses.

A traditional view has seen Revelation as primarily referring to Jesus’ supposed future “second coming” (a term never used in Revelation or anywhere in the Bible!). Recent scholars emphasize Jesus’ sacramental coming‒‒as evidenced by numerous “Amens” and other liturgical acclamations, as well as the setting of the book within the Sunday worship service (“on the Lord’s day” 1:10). The antiphonal call-and-response invitations to “come” in Revelation 22:17 may be part of a eucharistic dialogue. In worship, the book sweeps hearers up into a dramatic experience of apocalyptic transformation, leading to a new way of life, bringing the future into the present.

If the focus is on Jesus’ future coming in judgment, Revelation pronounces God’s judgment against the unjust Roman Empire, much more than the end of the world. The world is about to turn!

Alpha and Omega

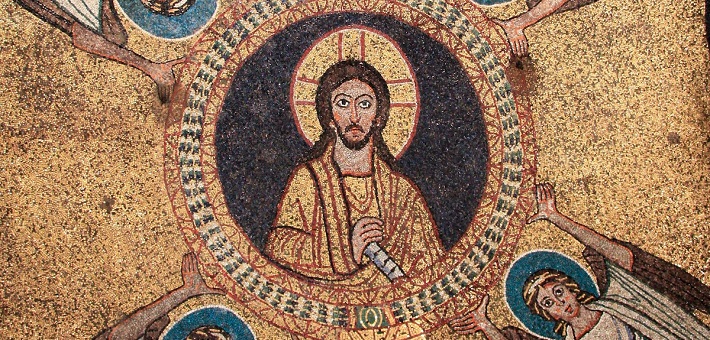

Only twice does God speak directly in Revelation (1:8, 21:5-7). “I am the Alpha and Omega” uses the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet to underscore God’s all-encompassing presence, from A to Z. The Alpha and Omega of Revelation 1:8 have inspired visionary art and music. This is a wonderful image with which to end one lectionary year and start another.

Notes

- See my chapter “The World is About to Turn: Preaching Apocalyptic Texts for a Planet in Peril” in Lisa E. Dahill and James B. Martin-Schramm, eds, Eco-Reformation: Grace and Hope for a Planet in Peril (Eugene: Cascade, 2016) pp. 140-159.

- Allen Dwight Callahan, “The Language of Apocalypse,” Harvard Theological Review 88 (1995) 453-70.

November 21, 2021