Commentary on Revelation 1:4b-8

Perhaps John could have packed more theological content into this little introductory passage, but we preachers may be grateful that he chose not to.

Here we find more than enough to chew on: the timeless glory of God, the faithful ministry of Jesus Christ, the benefits of our salvation, our hope in Christ’s glorious return, the fate of those who reject Christ, and God’s rule over every earthly dominion. Given the liturgical moment, we will concentrate on the message of Christ as “ruler of the kings of the earth” (Revelation 1:5) — and what Christ’s royal identity means for the status of believers.

Revelation unites the rule of Christ with the status of believers, and it does so in fascinating ways. Within this passage itself, we encounter Jesus as “the faithful witness,” “the firstborn from the dead,” and “the ruler of the kings of the earth.” Christ’s identity as king directly shapes the identity of his followers. Loved by and freed from their sins by Jesus, believers form his kingdom, in which they enjoy the exalted status of priests. His people serve within this “kingdom,” where Jesus enjoys “glory and dominion” forever.

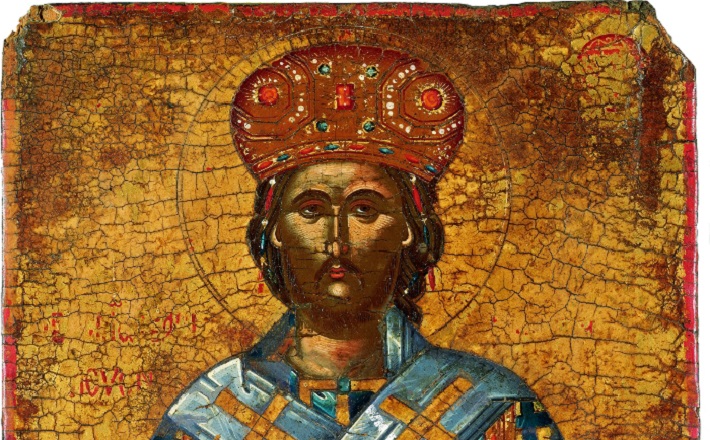

Preachers might note how this passage connects Jesus’ exalted status with that of God. All the high-flying language we encounter here ultimately points back to God. Yet Revelation has ways of blurring the identity of Jesus with that of God, indeed suggesting a very high Christology. The passage begins with a blessing from the one who sits on the throne, and it concludes with the Lord God proclaiming, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty” (1:8). Remarkably, this Alpha and Omega passage returns at the end of Revelation, apparently applying once to the one on the throne (21:6) but once to Jesus himself (22:13). Moreover, Revelation 7:9 portrays a multitude standing “before the throne and before the Lamb,” thus linking the Lamb’s authority with God’s. While Revelation’s throne language usually applies to God, Revelation 7:17 identifies the Lamb “at the center of the throne.” Indeed, Revelation 1:8 identifies God as the “Almighty,” in Greek the Pantokrator. Jesus as Pantocrator represents a prominent subject for Eastern iconography.

Revelation also identifies Jesus with his followers, and in ways that resonate well beyond this passage. For example, Revelation 1:5 identifies Jesus a “the faithful witness.” After all, Jesus demonstrated his faithful testimony to the point of death. Yet Revelation also calls believers to be faithful to the point of death (2:10), even pointing to a particular believer, Antipas, whose martyrdom meets that standard (2:13). By identifying Jesus as a faithful witness and as “firstborn of the dead,” Revelation ties Jesus’ glorious reign to his most inglorious death. If Jesus reigns through his faithfulness, so will his followers inherit his kingdom through their own faithful testimony (12:11).

This passage stands as the second stage in Revelation’s two-part self-introduction. Revelation 1:1-3 identifies the book as a revelation (apokalypsis) and as prophecy: that is, as inspired literature. But Revelation 1:4 presents the book as a letter, written to very specific groups of believers at a particular and challenging moment. The entire contents of the letter — and therefore the book — are ascribed to God and to Jesus.

Some who hear our sermons may consider Revelation out of step with the rest of the Bible. Several years ago a well-known theologian invited me to lunch. His question was, “What’s the matter with Revelation?” These verses certainly pack the potential for scandal: “on [Christ’s] account all the tribes of the earth will wail” (1:7, NRSV). Without question, Revelation gives voice to a desire for vengeance against those who reject the gospel and oppress Jesus’ followers. We may or may not be able to justify the desire for vengeance. From his own experience of political suffering, Allan Boesak claimed that the South African Apartheid government had “declared war” on its own people, recalling Revelation’s claim that the Beast had made war against the saints (Revelation 13:7; 12:17).1 Boesak famously proclaimed, “If [Christ’s] cloak is spattered in blood, it is the blood of his enemies, the destroyers of the earth and of his children” (124). Contemporary readers may debate Boesak’s comfort with divine wrath, but we can all acknowledge that serious moral and spiritual dangers attend the desire for vengeance.

I believe it is essential to take account of Revelation’s context when preaching this passage. In addition to Revelation’s desire for vengeance, modern hearers may struggle with the language of kings and kingdoms. To quote Boesak again, “Apocalyptic works reflect in the most dramatic way the response of the people of God to the pressures of their time” (17). Revelation’s audience knows all about kings and kingdoms — or emperors and empires — which they consider a mortal threat. Condemnation of the Roman empire, its ruler, and its practices permeates the Apocalypse. John describes the empire as beastly because it blends idolatry with domination (chapter 13), and he characterizes it as a prostitute (a disturbing image) because it so effectively turned diplomacy into economic exploitation (chapters 17-18). In contrast to empires that dehumanize, dominate, and exploit, Revelation offers a king who actually raises the status of his followers.

Was Bob Dylan correct in his assessment that “You gotta serve somebody”? Ancient people could imagine no alternative. Modern believers are wise to take that testimony seriously. In proclaiming Christ as a king whose very blood creates a new kingdom of priests, Revelation imagines an alternative to the powers that lay claim upon us. Christ’s lordship judges all other would-be authorities. It also marks Christ’s followers as holy people within a new community.

Notes:

1 Comfort and Protest: The Apocalypse from a South African Perspective (Louisville: Westminster Press, 1987), 37.

November 22, 2015