Commentary on John 18:33-37

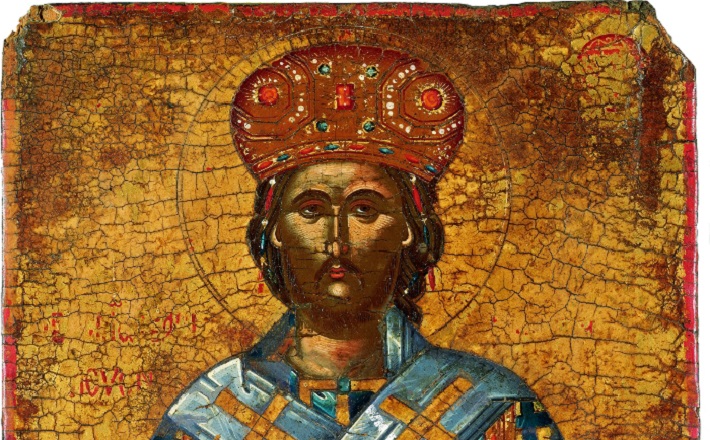

Who is truly powerful? Who reigns?

John’s trial narrative raises these questions in compelling ways. Although Pilate and the Jewish leaders may appear to be powerful, John presents Jesus as the one who exercises authority.

The charge of kingship is the central question of Jesus’ trial before Pilate. Jesus never answers Pilate’s question, “Are you the king of the Jews?” (John 18:33), in a straightforward way. As in other parts of the Gospel, John communicates some of the most important messages about Jesus’ identity by enacting them in the story instead of stating them outright. Here, John uses the trial and crucifixion to display Jesus’ kingship and the faithlessness of those who reject him.

Jesus refuses to answer Pilate’s charge of kingship directly. He states that his kingdom is “not from here” (John 18:36), which Pilate interprets to be an affirmation that Jesus is a king. Jesus also puts the question aside as something Pilate claims, and instead offers the idea that he is a witness to the truth (18:37).

Although Pilate declares to the waiting Jews, “I find no case against him” (John 18:38), Pilate should not be viewed as an innocent bystander swept along by the will of the Jewish authorities. He goes on to play against Jewish aspirations for political independence as he taunts the Jews with the idea of Jesus’ kingship. Pilate’s mockery of Jesus’ kingship is seen in John 19:1-7, where he has Jesus dressed in a purple robe and crown of thorns (19:2). He is beaten and then displayed to the Jews. The chief priests and police, seeking Jesus’ death, demand Jesus’ crucifixion. Pilate has put them in the position of demanding the death of their own king (19:6).

Pilate maneuvers in Jesus’ trial to appear as the one who crucifies the Jewish king. John recreates this scene of the demand for Jesus’ crucifixion twice. The second time, he underscores that it is the beginning of Passover, the moment when Israel would stop and remember God’s kingship and God’s rule over other powers. Instead, at that same moment, Pilate asks the Jews again, “Shall I crucify your king?” In their reply, “We have no king but the emperor” (John 19:15), John shows that the Jews’ rejection of Jesus leads them to deny God’s kingship and embrace Roman rule.

Part of the irony of John’s presentation of the trial and crucifixion is that Pilate uses his own authority to declare Jesus’ kingship. He places an inscription over the cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, the king of the Jews” (19:19). The chief priests protest, asking him to clarify that this was only what Jesus claimed. But Pilate refuses their request with a solemn pronouncement: “What I have written, I have written” (19:22).

In this way, John crafts his narrative so that Jesus’ kingship becomes most visible in his crucifixion. It is as if his crucifixion is his enthronement as king, the moment at which the declaration of his kingship is made public. Although all four Gospels record the inscription over the cross (see Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38), only John adds the extra details about Pilate’s interaction with the chief priests regarding the saying. John crafts the story so that the reader, who has known since John 1:49 that Jesus is “King of Israel,” sees Jesus’ kingship enacted even against the protests of the Jewish leaders.

As the crucifixion makes clear, Jesus’ kingship is “not of this world” (John 18:36). Worldly kings take power from others by winning battles or at least through successful diplomacy. Jesus neither fights nor allows his followers to do so. He does not mount a vigorous defense.

Instead, Jesus offers an alternative to earthly kingship. “I have been born and come into the world for this: to witness to the truth” (John 18:38). Jesus’ testimony to the truth appears embedded within the story of John’s Gospel. In chapter 19, the manner of Jesus’ death testifies to his true identity. Those who can hear or see the message of his crucifixion see a true king.

It is clear that many do not understand Jesus’ kingship, and others reject it outright. Throughout chapters 18-19, Jesus is “handed over” through a chain of command that implicates a number of characters as responsible for his death. Although Judas Iscariot is widely recognized as the one who “betrayed” Jesus (see John 18:2, 5), the Greek word translated “betray” also describes the actions of the Jewish leaders and Pilate. In John 18:36, Jesus uses this word to describe his being “handed over to the Jews.” Pilate also tells Jesus that the Jews “handed you over to me” (18:35). At the end of the trial, however, it is Pilate who “hands Jesus over” to be crucified (see 19:16). Thus the culpability in Jesus’ death does not rest with Judas alone but is shared through this action of betrayal or handing over.

Yet John is not content to present Jesus as the hapless victim of others’ betrayal. On the cross, it is Jesus who “hands over” his spirit (the New Revised Standard Version translates this as “gave up,” John 19:30). Jesus’ purpose, “to witness to the truth” (18:37), is enacted in this moment as well. In the end, it is Jesus, and not Judas, the Jews, or Pilate, who exerts authority over life and death.

John 18:33–37 begins a long scene in which the Gospel writer unfolds the reality of Jesus’ kingship. It is a kingship that can be difficult to see, for it is manifest in crucifixion rather than in political dominance. Today, Jesus’ kingship can be difficult to see for the same reasons. Preachers may want to use John’s story to make visible how, like the Jewish leaders, our allegiances to earthly powers lead us to deny God’s kingship. We may not even be aware that we have done so.

November 22, 2015