Commentary on 2 Samuel 23:1-7

Growing up in a rural, black Baptist Church, one of the songs I heard often was a spiritual, “Little David, Play on Your Harp.” That is the song that came to mind as I began to think about these purported “last words” of the idealized king David, son of Jesse. I think of this song because in the King James Version and the New American Standard translation of this pericope, one of the throne names David (or the editor of 2 Samuel) assigns to himself is “Sweet Psalmist of Israel” (23:1), translated in the NRSV as “The Favorite of the Strong One of Israel.” The range of meanings in the Hebrew can allow for the “Favorite of the Strong One” and for “The Sweet Psalmist.”

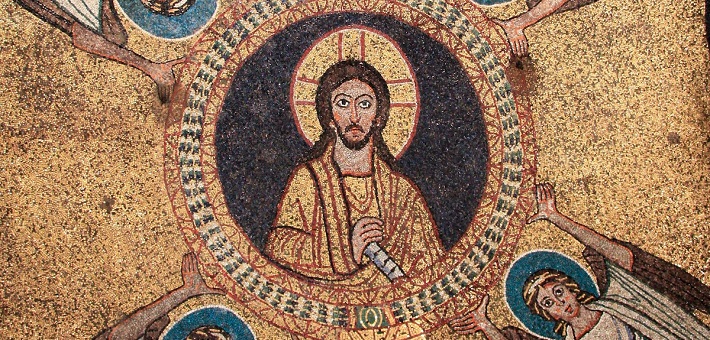

Part of why I have decided that the throne name that David chose is the Singer/Psalmist is because he is credited with the bulk of the psalms by most scholars, and it is through the psalms that we are made privy to David’s worship and worries, his praise, complaints and laments. Such a throne name would be in line with the expected anointed one. Because David is the prototype or the exemplar of the anointed one to come, in other words, the deliverer for ancient Israel, we see the other throne names in this first verse, “The One God Exalted” and “The Anointed of the God of Jacob,” connecting David at the end of his life to the beginning of ancient Israel’s history. The throne names are important as the biblical texts testify that God makes an everlasting covenant with the house of David (2 Samuel 7; see also 1 Kings 13:2; 2 Chronicles 21:7; Psalm 122:5; Zechariah 12:8).

Let’s assume that David is reminiscing and singing about what the spirit of God has spoken to and through him (verse 2). He makes the claim that he has ruled justly and in the fear of God. The description is of a ruler, beloved by God and people, for who wouldn’t love a just king? An astute scripture reader would have to remember that David’s reign and personal life has its blemishes. But, as a former hospice chaplain, I know that when people come to the end of life, their memories often soften to “clean up” the messiness of their lives.

I have no need to disabuse David or the people of this elevated view of his reign, one David describes as “like the sun rising on a cloudless day.” But I think the preacher has to be aware of the distance between our cleaned-up version of our actions and the lives we actually live. Another way of saying it is that we are all editors of our regrets in the end and hope that the good we did outweigh the sins that haunt us. Perhaps this last song affords David an opportunity to look back and reclaim the covenant God made with his house (though as Ralph Klein pointed out when he wrote on this passage, these “last words” are among ten “last words” recorded for David).

Since this text is for Christ the King Sunday, I know that those who added it to the lectionary are reading David as the once and future king, the ancestor of Jesus who is the ultimate anointed one of God. As Christians we are invited to read the text through that lens. This song points to a righteous ruler, which gives preachers an opportunity to think about what it would mean to reflect on governments, here and elsewhere and what just leadership would be in our times, one that reflects God’s desires. “Justly” is always to point toward material justice, what it means for people to eat, be free of violence, have what they need to survive, regardless of whether they are among the mighty or not. We see this reality reflected in the prayer for the king in Psalm 72.

This text is not in a vacuum as the rest of this chapter describes the warriors who worked for and with David. Ruling in the ancient world was always a bloody proposition. We must be careful not to make one-to-one correlations between the text and our times but look for the very human emotions that carry across the years. David’s song is a prelude to securing his kingdom for his house, even as he sings of an enduring covenant God has established.

There is no dissonance in the text between David’s behaviors and David’s question, “Will he not cause to prosper all my help and my desire?” (verse 5). What David’s question points us to is the reality that no human rules well without God’s help. History doesn’t make David look good, even as a ruler. Perhaps that’s the work of the Deuteronomist editors who were disappointed with Israel’s and Judah’s kings, believing them to have abandoned the King of Heaven. Perhaps they were disappointed with the kinds of deals that such rulers believed they needed to strike in order to have rest from war, a claim David makes in 2 Samuel 7.

Reading and reflecting on this pericope might lead preachers to think about how dishonest it is to act as if compromises don’t sometimes pull us away from God’s desire, but that compromises are necessary if nations are going to live in even a tenable peace. What must that mean as we go into Advent remembering the first coming of the Christ, anticipating a coming that will gather up our ragged history and bring into focus God’s shalom?

As the “favorite of God,” David looms large in the history of ancient Israel and throughout Jewish and Christian history. But thinking of David allows us to imagine a different world and even a different anointed one. That ability to imagine a different Christ is part of how this text leans us into Advent. As we prepare to sing of that first and future coming, we are reminded that David points to a desire for his progeny and is not the ultimate representative of God’s justice. But even as we note that truth, we have to hold ourselves accountable to our own softening of our sins, to our need for help, and to our longings.

The last verses here (verse 6-7) are typical to a psalm, where the ones “not like David,” in other words, “the godless,” are relegated to destruction because they do not desire the Holy One of Israel; they are thorns for a fire, like the chaff that the wind drives away (Psalm 1:4). In the Psalms (and though this text is in 2 Samuel, it is a psalm), what happens to the ungodly is in contradiction of the godly. David’s song here is making a distinction we see throughout the biblical texts between the godly and the ungodly. As preachers take up this text, we are invited not simply to distance ourselves from the ungodly, to name call, but to build a community where a just environment brings the ungodly in, rather than delight in their destruction. But we must confess that we have a propensity toward destruction, or, as this text suggests, that godlessness leads to destruction.

As the preacher struggles with this text and what it could mean this last Sunday before Advent, I would hope she would grapple with the fact that life has nuance to it, that nothing is as clear cut as David sings here. I’ve already mentioned that David’s remembrance of his reign leaves out the rough edges. But coming off All Saint’s Day and this last feast day of ordinary time, we are invited to God’s vision of the coming and present Immanuel, a reality that does not require a revised history.

November 21, 2021