Commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:23-26

This text is probably among the most familiar passages from the Pauline letters

Not only is it reflected in the Eucharistic liturgy, these verses are also included in the lectionary for Maundy Thursday every year. However, the lectionary’s focus on these few verses, excised from their context within 1 Corinthians, means that we don’t hear Paul’s point about how this supper should shape the life and character of the church. For a more full and fresh hearing of this text, the preacher may need to expand the narrow limits of the pericope to include all of 11:17-34.

It isn’t as though the pericope, as it stands, offers meager material. There is plenty here to ponder and proclaim. One good place to begin is with the wording of verse 23. How should we understand and translate, both in Bibles and in liturgy, the verb (paradideto) that describes what happened to Jesus on that night?1 The story we get when we translate the verb as “betrayed,” as in most English Bible translations and most versions of the liturgy, is that this night is primarily about human treachery.

The story being told would shift significantly if we understood this word according to its less sinister meaning, “handed over” (as New American Bible, and as Paul used the same verb earlier in verse 23). Though the Gospels use this verb to describe Judas’ action, Paul never does so. Paul does, however, speak about how God “handed over” Jesus for our trespasses (Romans 4:25 & 8:32), and how Jesus “handed over” himself for us (Galatians 2:20).

If all we hear in verse 23 is “betrayed,” then we have removed God from the story and handed it over to the machinations of human sin precisely where Paul intends to proclaim God’s redeeming grace. The church, all the way back to Paul and the tradition he received, has declared that this is not only a story of human betrayal, but is the story of God’s “new covenant” (25).

To hear only the story of Judas in the paradideto of verse 23 would allow no room for the gracious “for you” of verse 24. The cross is centrally an event of God’s love and mercy, and Paul’s attention is focused on God’s action rather than on human betrayal. It was on that night, as one ancient version of the Eucharistic liturgy says, that Jesus was “handed over to a death he freely accepted.”

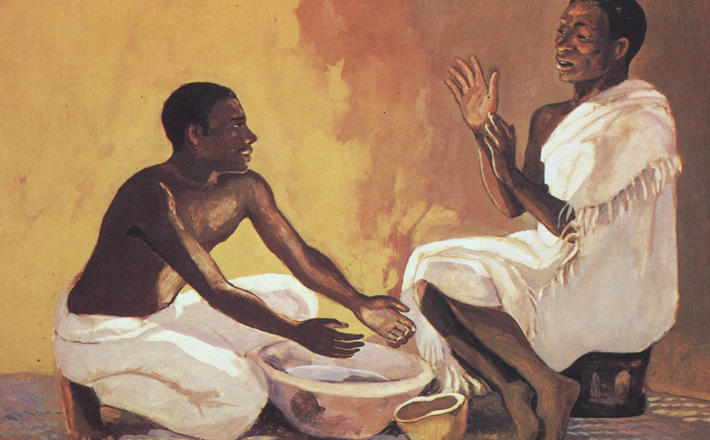

Since in the Supper we share in the body and blood of this Lord (10:16), Paul insists that the life of the church will be shaped accordingly. We will find, by God’s grace, that for the sake of the world we too are called to be handed over in service, in pursuit of justice, and in costly love for our enemies. We will find that the church too is called and sent in order to be poured out rather than to acquire, that we are sent to be broken for the sake of others rather than kept somewhere safe and unbothered. We will find that we too are called to stop “humiliating those who have nothing” (22) and to stand with them, or to sit and eat with them.

We become what we receive and consume: the body of Christ for the sake of the world. The story of the Supper is the story of God’s grace at work, beyond any human betrayal. It is God’s love “handing over” Jesus on the cross, and then into our hands and our mouths, and then through us into the world.

A second phrase that merits attention is Jesus’ own description of what the church does as “in remembrance” (24-25). Denominations have divided over the meaning of that phrase, and there is mystery here that we will not resolve in a short essay or in a sermon. However, one might remember that in the biblical tradition such remembering is never simply an act of mental recollection.

Rather, remembering means to have life and actions reshaped. When God remembered Noah in the ark or Israel in exile, the result was mercy and salvation. To “remember” God in Old Testament language is to repent and obey. For Paul to “remember the poor” in Jerusalem (Galatians 2:10) was not only to recall that they exist; rather, they became a life-changing concern. That this meal is done “for the remembrance” of Jesus is not just so we don’t forget the past. We not only meet our brothers and sisters at the meal; we also meet Christ (10:16), and our lives are given new focus by that reality.

It is that difference which the Corinthian church was denying every time they gathered together (11:17, 18, 20, 33, 34), because they focused on their own advancement even at the Supper (20-22). Though the self-promotional use of meals would have been socially expected, Paul says that it is a contradiction of the Supper and its Lord.

Paul’s solution to this distorted ecclesial life is not only to proclaim to them once again the narrative of the Supper, but also to call the Corinthian church to discernment. They are to “discern the body” (29). Paul makes his meaning clearer in verse 31 where he uses the same word: we are to “discern ourselves” (not, as NRSV, “judge ourselves”).

Paul’s concern is not (or at least not primarily) about the proper understanding of the sacramental presence of Jesus in the bread and wine, but about the recognition of the body of Christ in our brothers and sisters. To properly discern the body at the table means that we cannot come while leaving others uninvited and unwelcomed, or without mourning their absence. We cannot leave the table and be content to leave anyone hungry. To discern the body in the Supper will send us into the world with new eyes and new hearts, to encounter Christ there.

Notes:

1 See Brian Peterson, “What Happened on ‘The Night’? Judas, God, and the Importance of Liturgical Ambiguity.” Pro Ecclesia 20 (2011): 363-383.

April 17, 2014