Commentary on Exodus 12:1-4 [5-10] 11-14

On Maundy Thursday, we come to the Exodus account of the Passover.

An initial reading of the instructions for Passover in Exodus 12 displays several terms familiar to Christian communities of faith: lamb, blood, Passover, firstborn, judgments, etc.

Because of the gift of our New Testament, all of these words are wonderfully replete with theological meaning. But I ask you, Working Preacher, as you study this text, to set aside the lens of Pauline Christology. Instead, I invite you to examine the text from the perspective of a typical household in ancient Israel.

Long after the exodus event, these Passover instructions continued to circulate to many generations in ancient Israel. The Passover quickly became a sacred text to the Israelites. A public reading of “Torah” compels both Josiah (2 Kings 22:8) and Ezra (Nehemiah 8:2-3) to lead their communities in new and bold ways.

Undoubtedly, the specific instructions for Passover were a crucial component of Israelite life. Just like our Christmas and Easter traditions, every Israelite would have a collection of memories of their experienced Passover traditions, occurring on the tenth day of the first month of the Hebrew year.

God commanded the Israelites to take a one year-old lamb without blemish. I suspect the lamb without blemish would have been identifiable as Passover-suitable from its birth. If this was the case, then the remembrance of the Passover festival was not restricted to the tenth of the first month, but rather hints that the Passover infiltrated the seemingly mundane life of raising the lamb.

For the entire year leading to the Passover, every feeding and every aspect of care allowed the family member the opportunity to remember that this lamb may be preserved for the Passover. In many ways, the Passover was to be remembered throughout the year, merely culminating in the Passover celebration.

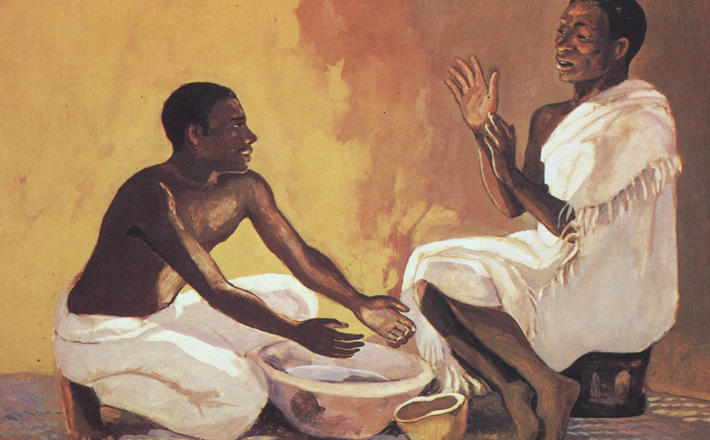

The condition in verse four is powerful, “If a household is too small for a whole lamb, it shall join its closest neighbor in obtaining one.” This simple accommodation widens the worshipping community to those who have economic hardship. The act of sharing the lamb with smaller families (such as a family of one?) enacts the cycle receiving and dispensing of grace to share in their remembrance. I wonder on the implicit morality demonstrated to the young children of Israel, as they saw households joined in this celebration.

The meal is unique. In partaking of the lamb, no leftovers are allowed. The instructions give an urgency to the meal, eating while ready to go. Of course, most parents know that children often cannot be convinced of any necessary urgency in meals. I wonder how the children would respond to such commands, as well as the accompanying explanation of the patriarchs or matriarchs of the household recounting the frenetic activity of the families during the Exodus narrative.

Verse twelve declares that the punishment of God on the nation of Egypt, an incredibly rich, powerful, and long lasting dynasty, would be swift thereby revealing the judgment of God. But verse thirteen states that the blood of the lamb will save the household. According to Torah, blood is life and consequently blood is redemptive of life (Leviticus 17:11-14). The agrarian-minded Israelites readily understood blood as the very core component of the living.

Interestingly, Exodus 12:13 gives us the theological detail, “The blood is a sign for you,” referring to the people of Israel. The blood is not for God to identify the houses, for God already knows the divine promise for protection and its application. But by using the blood as a sign, the people can know and see this reminder that God will deliver his promise.

Now, look at the passage again, this time with the understanding of the theology of the New Testament. Remember, the earliest Christian community was a Jewish community. They were a people steeped in tradition and ritual, and they understood the gravity of the Passover, as presented here as well as in Leviticus 23. By the providence of the genetics, the lamb was likely identified from birth as a Passover lamb, nourished and raised for the special day of remembrance for a community. The lamb was to be shared across normal economic lines, thus bringing the nourishment of the meal and the protective powers of the blood to identify and protect a unified community.

And this activity was to be carried out every year, from the tenth day of the first month in order that all generations may share in the joy of the Lord, the forgiveness of sins, and miraculous deliverance from the blood of the lamb. In this sense, the Passover was not a singular event in the course of a year, but the culmination of a year’s worth of continual activity in raising this lamb and remembering the deliverance of God during a people’s time of need. For the New Testament community, this Jewish Passover provides the theological foundation for understanding the Lord’s Supper; for by the blood of the lamb, we are delivered from Egypt.

Soli Deo gloria.

April 17, 2014