Commentary on Exodus 12:1-4 [5-10] 11-14

These verses, the institution of the Passover, are the appointed lectionary Old Testament text for Maundy Thursday each year. As such, they are likely seldom the object of focused preaching—getting lost in the other days of the Holy Triduum or playing “backup” to the Lord’s Supper. These verses may also seem an unlikely place from which to mine a sermon; they read more like a segment from Leviticus, with focus on proper preparation, sacrifice, and ritual. And they interrupt the much more compelling plague narrative right at its highest crescendo in the battle between YHWH and Pharaoh, with the announcement of the final plague: the death of the firstborn.

Brevard Childs writes about this text that “God’s redemption is not simply a political liberation from an Egyptian tyrant, but involves the struggle with sin and evil, and the transformation of life.”1 Both avenues are important and vital in considering this formative and foundational story.

Memory in a meal

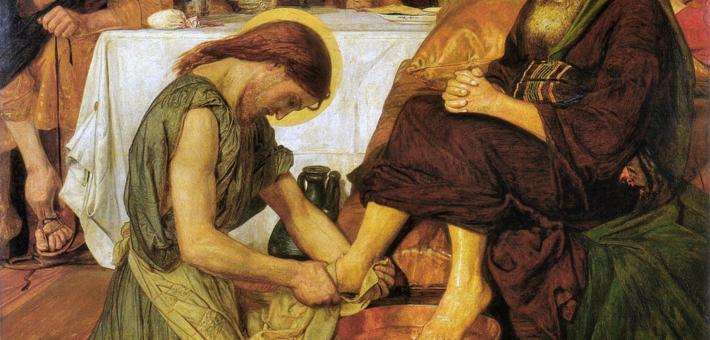

Both Israel’s liberation from bondage in Egypt and Jesus’ journey to the cross begin with a meal—a startlingly simple meal deeply concerned that all could participate. Provision is even made for the poor and for smaller households, which are commanded to join with one’s neighbor and share the sacrifice (verse 12). So, too, at Christ’s table all are welcome.

This odd bit of interjected liturgy concludes with these words: “This day shall be a day of remembrance for you. You shall celebrate it as a festival to the LORD; throughout your generations, you shall observe it as a perpetual ordinance.” Passover, then, is more than mere past event; it is a liturgical moment to be experienced time and again, from generation to generation. It is a participatory event for the worshiping community throughout the ages, remembering and celebrating how God continues to work liberation. Still to this day, in Jewish liturgy of the Passover, they remember and celebrate that “God brought us out of Egypt.”

So, too, is the institution of the Lord’s Supper tied up with memory and the worshiping community’s participation in a past event with enduring promises in the present and implications for the future (Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:23–26).

New beginnings for a new community

The liturgical moment of the Passover marks a decisive new beginning for God’s people. The Lord instructs Moses and Aaron, “This month shall mark for you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year for you” (verse 2). It becomes the event that establishes the cadence by which God’s people will mark time as they recall God’s mighty act of deliverance. Everything will be based on this moment. While the Egyptians marked their calendars by the sun and moon’s appearance, the Israelites mark their calendars with this story. Passover births the people Israel.

Passover also begins to cast its glance toward the future, anticipating the ways God’s salvation will continue to shape Israel-as-slaves into Israel as a holy, liberated community. Again, the instruction to join houses together in acquiring the sacrificial animal begins to knit together a community that can rely on one another. Moreover, the admonition that there are to be no morning leftovers—“You shall let none of it remain until the morning; anything that remains until the morning you shall burn with fire”—anticipates God’s provision of manna and quail in the wilderness, where, likewise, none was to be left until morning and only what one needed was to be gathered (Exodus 16:13–21, especially verse 19). The specifics of the first Passover begin to establish Israel’s absolute reliance on and trust in God.

The ongoing, unsettling work of liberation

The work of Passover is intimately bound up with resisting oppressive empires. For the Israelites, it was the slave-driving empire of Egypt; for the disciples gathered at the Lord’s Supper, it was the cruel Roman Empire, which would soon crucify Jesus.

Just as Passover is not a one-time past occurrence, neither is the work of liberation just a past event, but is always in process, needing to be proclaimed and pursued again and again for each generation.

But there is a deeply unsettling aspect to this celebration of liberation: It comes only, finally, through the death of the firstborn. How can we “celebrate” Passover “as a festival to the LORD” (verse 14) when it is shot through with such barbarity? When Jesus enjoins us, “Love your enemies; do good to those who hate you; bless those who curse you; pray for those who mistreat you” (Luke 6:27–28)?

Maintaining that it is God, and not the Israelites, who carry out this dreadful act does not mitigate its horror. Indeed, rabbinic writings from the third century CE cautioned Israel against celebrating Passover with exuberance at the fate of the Egyptians. A midrash on the drowning of the Egyptian army in the Red Sea sees God chastise the rejoicing angels in heaven, saying, “Are you to sing while my children are destroyed?” And still today, when Jews celebrate the Passover seder, they remove a single drop of wine from their glass as each plague is mentioned, acknowledging that their liberation came at great cost to their oppressors.

This dialectic continues to be incredibly challenging to balance. It is not difficult to identify present-day situations in which the innocent suffer more than any other for the sins and hardened hearts of their leaders. How might we read such a story in light of recent events, including forced migrations that undo the work of liberation, returning others to bondage from which they are trying to escape (or have already escaped)?

Perhaps the most helpful takeaway is to recognize that the command to keep the Passover alive in the memory of the faith community means we are called to continue to enact, to practice Passover (read: liberation) still today, drawing attention to and working to dismantle any and all systems that enslave or oppress. The work of Passover continues to be much-needed today.

Jesus the Passover Lamb

Space precludes a fuller treatment of this topic, though much has been rightly made of the New Testament’s appropriation of the Passover as prefiguring the saving, liberating work of Christ. The final meal Jesus celebrates with his disciples in the upper room is a Passover meal (Matthew 26:17–29; Mark 14:12–25; Luke 22:7–28).

John’s gospel is unique in placing the meal on the day before Passover, even more intentionally making the important theological linkage between Jesus and the Passover sacrifices. Christ then becomes the ultimate paschal sacrifice whose blood sets us free (John 1:29, 36; 1 Corinthians 5:7; 1 Peter 1:18–19; 2:22; Revelation 7:14; 12:11). In the Christian reimagining of Passover, it is God’s firstborn Son who becomes the sacrifice; the suffering of others in the work of liberation becomes God’s own suffering. In Christ, it is God who does not withhold God’s own firstborn.

The menu, then, for the Last Supper of bread and wine (unleavened bread is mentioned in Exodus 13) is similar to that of Passover when Christ is viewed as the sacrificial Lamb. This, too, inaugurates a new community of faith that continues to remember and share in this sacred meal together until the day Christ comes again.

Notes

- Brevard S. Childs, The Book of Exodus: A Critical, Theological Commentary, Old Testament Library (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1974), 213.

April 17, 2025