Commentary on John 13:1-17, 31b-35

Anyone who has experienced the fraught dynamics of a middle-school lunchroom can intuit the social, political, and even existential importance of these meals—perhaps the very mention of it stirs a bitter memory in your gut.

The middle-school lunchroom is a microcosm of the world, with all of its complexities and hierarchies on display through the dynamic negotiations contained within. Who eats with whom—and who’s excluded? What is gossiped about or discussed, and what is eaten? (Regular meal? A la carte? Free or reduced lunch? Lunch bag? Nothing?) Ultimately, these meals reveal and inscribe which relationships and communities hold the power, and how that power is exercised. Will it be in exclusion and diminishment, or in love and empowerment? God be with the new student forced to navigate these challenges on day one, and with those already at the table!

In not dissimilar ways, communal meals in Greek and Roman antiquity were tools of power that displayed and reinscribed the social, political, and existential values of their time. Roman imperial private banquets were famous affairs, calculated spectacles of extravagant wealth and power and replete with exotic food, luxurious tableware, and impressive entertainment, intended to keep friends close and enemies closer.

Domitian, the imperial “Lord and God” (see also John 20:28) who ruled when the Gospel of John was likely being composed, put a macabre spin on dinner in his infamous “Black Banquet.”1 Cloaking the room and slaves in black and serving black-dyed funerary food, Domitian arranged his guests next to personalized tombstones while they nervously anticipated summons to execution. Though ultimately a prank (the guests left with gifts, including slave boys), the message of absolute imperial power could not have been more serious. Even accounting for slanderous bias in the Roman sources, this meal (along with others) was a damning display of “power dining.”

How different is this meal in the Gospel of John with Jesus, cast in this book as the supreme rival to the “ruler of the world” (12:31). Notably, in John this last supper is not a Passover meal (contra the Synoptics and lectionary pairing with Exodus 12), so a different interpretive lens is needed. First-century audiences would understand the references to Jesus “rising up” (13:4) and to the group “reclining” during the dinner (13:23, 25) as suggesting a Roman-style banquet room (triclinium), a U-shaped table where guests recline on couches. What type of banquet is this, though, and what message (or messages) does it perform?

The banquet is introduced as a power meal (13:3), asserting that God had given all things into Jesus’ hands. The emphasis is not fear, but love: Jesus’ love for his own (13:1), and the commandment for his disciples to love one another in emulation of Jesus (13:34–35). These framing references to love invite us to read all that transpires within the dinner as actions of Jesus’ authority and (countercultural) power performed under the auspices of love.

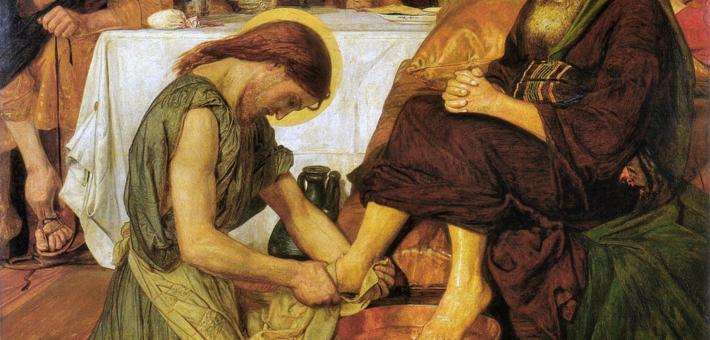

Noticeably absent from the description of the meal are depictions of the room, the identification of the patron, or the sumptuousness of the meal—these are not characteristics of the nature of Jesus’ powerful movement. The only “fashion” mentioned is Jesus’ outer garment, and his girding of himself in a towel in the manner of servants and workers (as seen in clay objects). Simply put, Jesus dresses like a slave, and then acts like one in the singularly emphasized main program of the banquet: Jesus’ washing of the disciples’ feet. This humble act, typically performed by a slave upon the arrival of guests to dinner, is unusually shifted to the middle of the meal in John’s account (13:4–5), the place typically reserved for entertainment or discussion, making it “the main event.”

This action and teaching turn the typical imperial “power meal” on its head, transforming hierarchies of power by depicting Jesus engaged in low-status service to his disciples, despite (or because of) the Father having put all things into Jesus’ power. The exemplary character of this act is explicit: “So if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you” (13:14–15).

In essence, Jesus exemplifies his “Lordship” precisely through this humble act of loving devotion. How notable it is that the hands that hold “all things” are used to wash the feet of the lower-status disciples—even the heel that is lifted against Jesus (13:18). One could scarcely imagine Domitian washing the feet of his dinner guests, highlighting the ways in which Jesus’ movement threatens the nature of Roman imperial values and power.

The lectionary reading culminates with another exhortation to emulation, the commandment (mandatum in Latin, from which “Maundy Thursday” derives) to love one another, just as Jesus has loved them (13:34). The countercultural nature of this love is revealed by the focus on two specific disciples in the passage: Judas and Peter. Together, these two disciples represent various failures of faithfulness, yet by focusing on them, we get a sense of the scandalous, unmerited character of Jesus’ love for “his own” (13:1), which extends even to the fallen and the fearful.

In horrifying knowledge of what is to come (and regarding Judas, without whitewashing the evil nature of his betrayal), Jesus nonetheless washes the feet of both, and exhorts his disciples (then and now) to exercise the same love. The textual variant in 13:2, which places the footwashing after dinner (and hence after Judas’s departure [13:30]), reveals scribal discomfort with this unseemly love—a discomfort likely shared by some in the church today.

Thus, the challenge remains: Are we known today by our love for one another—even for the deniers and betrayers? What would it look like if we, like Jesus, were so rooted in God as our origin and our destiny that we had the freedom and power to direct our love to empower and liberate one another (13:3)? The passage doesn’t note how the other disciples responded to the footwashing and the command to love one another, whether they sought out Judas after he left, or offered a bed to Peter after he denied Jesus; that response is to be written by us. Among those in our lives, whose feet and their stony paths could use some hands-on love and tenderness?

Notes

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 67.9.1–3

April 17, 2025