Commentary on Luke 16:19-31

As much as we would like to spiritualize the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus, it is very difficult to explain away its central message, especially given what Luke has to say about money and possessions elsewhere in his Gospel.

The fates of these two individuals after death are very much tied to their experiences of wealth and poverty in this life.

The rich man has no name, although he’s been given various names in later history such as Dives, which means “rich” in Latin. By contrast, Lazarus is the only name given to anyone in Jesus’ parables; it means El-azar, “God has helped.” (There appears to be no connection between this Lazarus and the resuscitated man in John 11:1-44.)

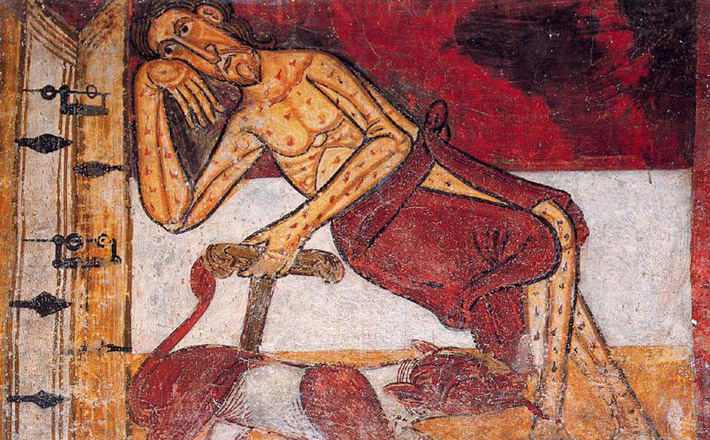

The story begins with a drastic reversal that happens after these two men die (16:19-23). In his lifetime, the rich man ostentatiously displayed his wealth with beautiful clothes and lavish feasts. Conversely, Lazarus was covered with sores, was hungry, and had only dogs to lick his sores. After his death, Lazarus is carried away to an honored place beside Abraham, God’s friend and the father of Israel (3:8; 13:28-29). By contrast, the rich man finds himself in Hades, a place of torment and eternal punishment (10:15).

A conversation ensues between the rich man and Abraham (16:24-26). The rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus to ease his pain in Hades, but Abraham responds that this cannot be done. Their fortunes have shifted. In their lifetimes, Lazarus suffered bad things and he experienced good things, but now Lazarus is comforted and he is in agony. A “great chasm” now exists between the two, which cannot be crossed.

The rich man then begs Abraham to send Lazarus to warn his five brothers about Hades (16:27-41). Abraham replies that they already have Moses and the prophets to warn them. This response is congruent with Luke’s emphasis on the continuity between Jesus’ teaching and that of Moses and the prophets (see 24:26-28; 44-48; see also 16:16-17). When Lazarus maintains that his brothers will change their ways if someone comes to them from the dead, Abraham replies if they have not listened to Moses and the prophets, they definitely will not be convinced by someone being raised from the dead, an allusion perhaps to Jesus’ resurrection (9:22; Acts 1:22).

The story centers on the reversal of fortunes that takes place after Lazarus and the rich man die. It links agony or comfort after death with how we treat the less fortunate around us, much like Matthew links eternal life and punishment with how we treat the hungry and thirsty, strangers, the naked, the sick, and those in prison (25:31-46). This reversal after death is ultimate. An unbridgeable chasm exists between Lazarus at Abraham’s side and the rich man in Hades.

Luke, in particular, stresses the way the status of the rich and the poor is reversed in the kingdom of God. When Jesus is conceived in Mary’s womb, she exults that the hungry have been filled and the rich sent away empty (1:46-55; cf. 1 Samuel 2:1-10). In the Sermon on the Plain, Jesus tells the poor that God favors them and that the kingdom of God belongs to them, but he warns the rich of what is to come since they have already received their consolation in this life (6:20-25).

Luke makes clear that the poor are a focus of Jesus’ ministry. In his inaugural sermon, Jesus declares that he has been anointed by the Spirit of the Lord “to bring good news to the poor” (4:18; see also 7:22). Jesus admonishes his followers not just to invite to their parties the friends and neighbors who can repay them, but to extend their invitations to “the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind” (14:13). This is echoed when Jesus describes the kingdom of God as a wedding banquet where the invitation has been extended to “the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind” (14:21).

Yet if the poor have good news preached to them, then the rich receive a somewhat different message. The rich young ruler who asks Jesus how he can inherit eternal life is told that he is to sell all he has and distribute the money to the poor. When this makes him sad (because of his wealth) Jesus comments that the rich tend to have more difficulty entering the kingdom of God (18:18-30). Like the rich fool, the wealthy store their treasure in ever larger barns they cannot take with them after they die (12:8-21). They may store up “treasures for themselves,” but they are not “rich toward God” (12:21).

But being “rich toward God” — and having “treasure in heaven”– is not just about piety. It is also about selling possessions and distributing wealth to the poor (12:33; 18:22). After he encounters Jesus, Zaccheus gives half of his possessions to the poor and repays anyone he has defrauded four times as much (19:1-10). As the church emerges in Acts, new converts would “sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need” (2:45; 4:32-34).

The story of the rich man and Lazarus might be difficult for many North Americans, whose lifestyle stands in sharp contrast with a majority of people in the world who live on much less. Like so much else that Luke says about money and possessions, it stands as a stinging indictment not only of the great confidence we place in financial security, but also of the drastic inequities between rich and poor we allow to perpetuate.

In this story, God’s eternal judgment has everything to do with how we use wealth in this life and whether we attend to those less fortunate in our midst. Our temptation is to explain away a story like this and to remove its blatant depiction of how God will ultimately vindicate the cause of the poor. But the message has been clearly stated. Like the rich man’s five brothers, we have been given all the warning we need.

September 29, 2013