Commentary on Luke 16:19-31

Unique to Luke is the story of the rich man and Lazarus.

It follows last week’s parable about a rich man and Mammon. The entire chapter can be entitled “Rich Men and Lovers of Money,” suggests Alan Culpepper, in order to underscore the thematic unity of the two parables.1 The rich man’s sumptuous feasting (“making merry,” euphrainomenos) also echoes the “eat, drink, and be merry” boast of the man with bigger barns in Luke 12:19.

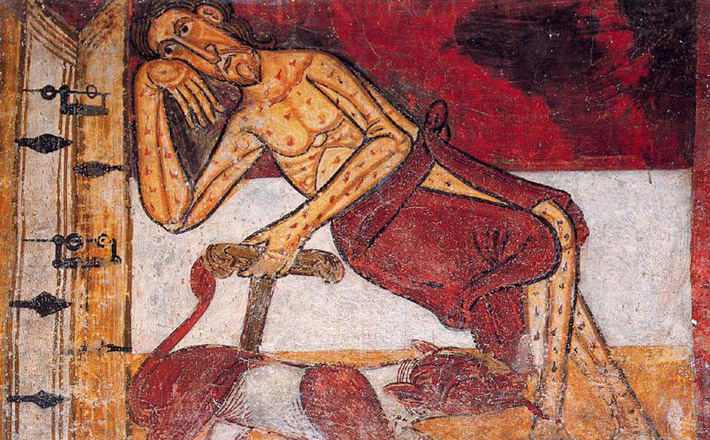

With its vivid journey to the afterlife, and its exaggerated imagery of contrast, this parable fits the form of an apocalypse. An apocalypse serves as a wake-up call, pulling back a curtain to open our eyes to something we urgently need to see before it is too late.

During his life the rich man did not even see the poor man who was at his gate each day. Now, in the afterlife, he sees Lazarus — but too late. The parable portrays a permanent chasm fixed between the rich man and poor Lazarus, with no way to cross over the chasm. The exaggerated apocalyptic contrasts are many: the lavish meals of the rich man’s table in life, contrasting with his unquenchable thirst after death; the deathly poverty of Lazarus, contrasting with his rest in the bosom of Abraham. These contrasts underscore the parable’s function as urgent warning.

Where does Luke intend the audience to see itself in this parable? The image of vindication in Abraham’s bosom is a wonderful one, offering comfort for those in Luke’s audience and those in the world today who are as poor as Lazarus. The image of resting in the bosom of Abraham inspired the African American spiritual “Rock My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham.” But beautiful as this image is, the primary message of this parable is probably not comfort.

In Martin Luther’s day, the parable inspired much speculation about where we go after we die.2 The location of the bosom of Abraham in relationship to heaven, and whether we go there immediately following death, or must wait for the resurrection at the Last Day, were the primary concerns for Luther and his contemporaries — also inspiring Luther’s critique of purgatory. In a 1523 sermon on this parable Luther argued that the bosom of Abraham was not a place, but the Word of God. “Thus were all the fathers before the birth of Christ carried into Abraham’s bosom; that is at death they were established in this saying of God and fell asleep in the same, they were embraced and guarded as in a bosom, and sleep there until the Day of Judgment.”3 In other writings, Luther struggled to clarify the relationship between death as sleep awaiting the Last Day, and the role of Sheol and the bosom of Abraham in the interim time.

But the parable was probably not originally intended as didactic explanation of the afterlife. To understand the meaning, we should turn to the three responses of Abraham denying the rich man’s requests to “send Lazarus” (Luke 16:24, 27). Tenderly but firmly, Abraham refuses each of the rich man’s requests. He even calls the rich man “child,” making clear that being a child of Abraham is no guarantee of salvation. For the rich man, it is too late. Abraham will not send Lazarus to help the rich man after death.

Apocalypses often have a hortatory function. With their exaggerated imagery apocalypses offer a wake-up call, a warning, like the dream sequences of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.4 If this parable is an apocalypse, then Luke is situating the audience not so much in the role of either Lazarus or the rich man, but in the role of the five siblings who are still alive. (The Greek word adelphoi can also be translated “siblings” — it includes sisters as well as brothers.) The five siblings who are still alive have time to open their eyes. They have time to see the poor people at their gates, before the chasm becomes permanent. “Send Lazarus to them, that he might warn them,” cries the rich man on behalf of his brothers and sisters, “so that they do not come to this place of torment.” The terrifyingly vivid apocalyptic journey to Hades awakens a sense of urgency on the part of Luke’s audience.

We are those five siblings of the rich man. We who are still alive have been warned about our urgent situation, the parable makes clear. We have Moses and the prophets; we have the scriptures; we have the manna lessons of God’s economy, about God’s care for the poor and hungry. We even have someone who has risen from the dead. The question is: Will we — the five sisters and brothers — see? Will we heed the warning, before it is too late?

In Luke’s wonderful imagery, Abraham’s bosom awaits to enfold us in loving arms now and after our death.

Notes:

1 Alan Culpepper, “Luke” The New Interpreter’s Bible, vol. 9 (Abingdon, 1995) 315.

2 See James Kroemer, “Doctor Martin, Get up”: Luther’s View of Life After Death,” in Deanna Thompson and Kirsi Stjerna, eds., On the Apocalyptic and Human Agency: Conversations with Augustine of Hippo and Martin Luther (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2014), p. 40. Kroemer chronicles Luther’s gradual rejection of the concept of purgatory in favor of the conviction that souls “sleep” until the Day of Judgment, drawing on Luther’s sermons as well as his commentary on 1 Corinithians.

3 WA 10 III:177-200. Kroemer states that “The translation is from Sermons of Martin Luther IV, ed. John Nicholas Lenker (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1989), 16-38. WA gives June 22, 1522 as the date of the sermon.”

4 See Barbara Rossing, The Rapture Exposed: The Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation p. 85-86 on this parable as an apocalypses.

September 25, 2016