Commentary on Luke 16:19-31

An enormous and growing wealth gap separates a few—both individuals and nations—from the many who live in poverty. Sound familiar? First-century life within the Roman Empire was much like the reality we know, in this regard. The Gospel of Luke assumes and addresses this reality.

Luke 16 follows the most enigmatic of Jesus’ parables, that of the dishonest (or shrewd) manager (in verses 1–13), with one of the most memorable and difficult, the parable featuring Lazarus and a rich man (verses 19–31). It is challenging, not because its meaning is hard to grasp, but precisely because its message is crystal clear.

Immediately preceding the parable that concludes the chapter, Luke presents a set of loosely related sayings about wealth, entrance into the realm of God, and the continuing validity of the law and the prophets (verses 14–18). The motif of wealth and the claim of law and prophets prepare readers for the story that follows.

Scene one: Life-threatening poverty alongside conspicuous wealth

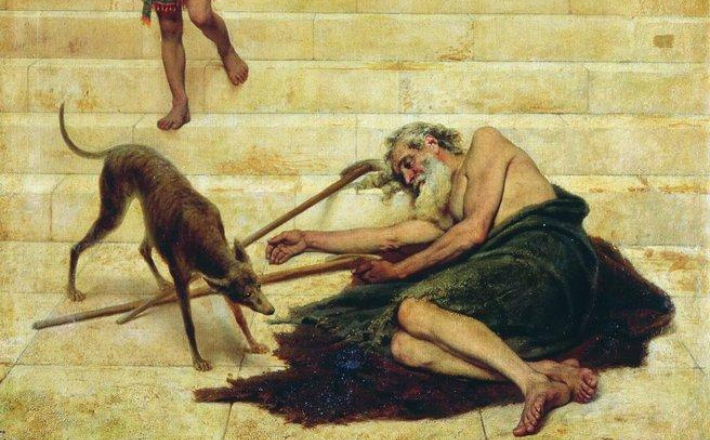

Verses 19–21 paint the starkest contrast between the lives of two men who exist in the closest proximity. We first meet a man who displays his enormous wealth in clothing (expensive purple garments and the finest linen) and lavish daily banquets. Then we see, deposited at the gate right outside his home, a destitute man whose physical health is compromised—he is desperately hungry and “covered with sores” (verse 20, New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition; this might also be translated “wounds”). Dogs lick the man’s sores or wounds, perhaps compounding his suffering, although this may be an image of comfort, if the notion that a dog’s saliva has curative effects is in play.

While the rich man is unnamed, this man receives a name: Lazarus, a form of the name Eliezer. As this is the only named human character in a parable of Jesus in the Gospels, apart from Abraham in this story, the symbolic meaning of his name is especially meaningful. As the story unfolds, God—and only God—is his help.

Scene two: Trading places—you can’t take it with you

The men and their experience of life could not be more different, but the story takes a dramatic turn in verse 22. Death intrudes, and while Lazarus is carried by angels to be with Abraham, the rich man receives the honor of burial—presumably a dignity denied his impoverished counterpart. From Hades, the place for the dead that is now his home, he spots Lazarus “far away” right next to Abraham, and an extended dialogue ensues between the wealthy man and “Father Abraham.” Family language is prominent in the scene, connecting the patriarch and his “child.” Claiming to be a descendant of Abraham, however, is no guarantee of a place within God’s realm, as John the Baptizer made clear earlier in the narrative (Luke 3:7–8). For Abraham’s family, too, it matters how one lives!

The dialogue reveals that the rich man knows well who Lazarus is. He calls out Lazarus’s name as he begs Abraham for mercy: Dispatch him to bring comfort and relieve my pain “in these flames” (16:24, New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition). No help is forthcoming, however; there is now an unbridgeable chasm between two men who once were separated only by a gate.

Abraham explains the principle that is at work, a radical reversal of circumstance that is reminiscent of Jesus’ earlier declaration of blessing and woe: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled. Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh. … But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry. Woe to you who are laughing now, for you will mourn and weep” (6:20–21, 24–25).

Does Lazarus enter into bliss simply because he had been poor? Does the rich man now suffer simply because he had prospered? The parable intimates that the blessing of the one who suffered poverty is a matter of sheer grace, apart from anything he does. (In fact, the story gives him no agency at all. Persons today who experience poverty do have agency, can and do make many decisions—though the range of possible actions is so often extremely limited due to circumstances beyond their control.) Yet for the rich man, it is not wealth alone that causes his demise, but his failure to act generously toward the man he encountered outside his home every day. With wealth comes great responsibility.

Epilogue: What about the rest of my family—and what about us?

So there is no hope for the rich man, but the story doesn’t end there. Is there hope for the man’s five wealthy brothers? Family language continues as the dialogue pivots back to this world and this life (verses 27–31). No, Lazarus can’t be sent back to the living (like Marley’s ghost to Ebenezer Scrooge in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol) to issue a warning. If these brothers know the law and the prophets, they already know what God expects of them. Not even resurrection from the dead will work a miracle of repentance, a premonition in Luke’s narrative of things yet to come in the Acts of the Apostles.

It is too late for the rich man, and there appears to be no hope for the rest of his family. But what about us? In this fictional narrative, Jesus invites listeners to examine their own life choices and actions in light of the reality that we have limited time in which to live well. We will have only so many opportunities to do the right thing. It is not too late for us: Not too late to pay attention to the needs around us. Not too late to share what we have to help others flourish. Not too late to challenge business practices and economic systems that allow a few to enjoy massive wealth while others experience unrelieved, crushing poverty. The work of this parable isn’t finished until we answer the question: How will we respond?

September 28, 2025