Commentary on Amos 6:1a, 4-7

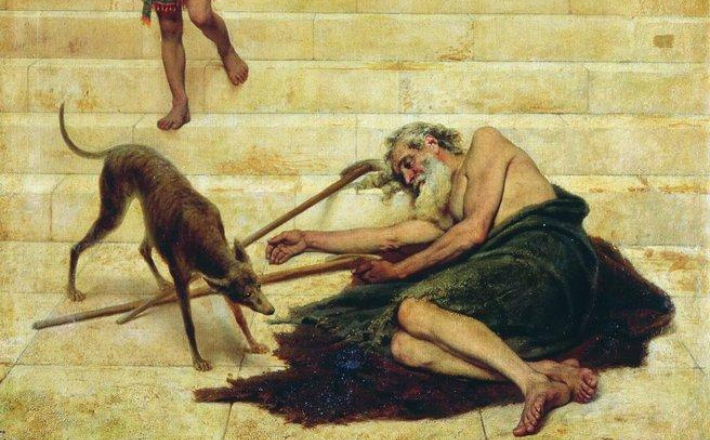

In Amos 6, one is confronted with a picture of utter opulence. At the pinnacle of luxury, people are reclining on ivory beds. They eat meat every day, the most succulent lamb and calf, while the rest of the population only consumes meat during festivals. They enjoy leisurely meals accompanied by dinner music, trying their hand at songwriting like David, while others are working. They are drinking wine from bowls, not goblets. And they beautify themselves with the best cosmetics available.

This picture of wealth and self-indulgence at their worst sounds all too familiar these days in what has been described in certain areas as a new Gilded Age. Social media and reality TV sell luxury goods and designer brands enjoyed by the few but coveted by the many. All the while, the gap between rich and poor has been growing more pronounced.

In this week’s lectionary text, the Southern prophet Amos, an incidental prophet called by God while going about his daily business tending sycamore trees and his flock of sheep, offers a strong rebuke of both his fellow countrymen and -women as well as their Northern cousins regarding the profound self-absorption that is a side effect of utter opulence:

Woe to those who are at ease in Zion

and for those who feel secure on Mount Samaria. (verse 1)

According to Amos, affluence and self-indulgence make one oblivious to the needs of anyone but the self and the self’s inner circle. Amos laments that because of their opulent and comfortable lives, they “are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph” (verse 6). Elsewhere in Isaiah 5:8–13, this lack of empathy and inability to see the plight of the poor is attributed to drunkenness—perhaps also implied in light of the reference in Amos 6:6 to bowls of wine!

The strong indictment in verses 4–6 is followed by harsh judgment in verse 7. In one of its first occurrences, the term “exile” is used in an ominous prediction of what is to come or, if stemming from a later time, as an explanation for what already has occurred. The judgment continues in the next pericope, which speaks of great suffering and hardship that will come over the land since they “have turned justice into poison and the fruit of righteousness into wormwood” (Amos 6:12). Wormwood, as also in Amos 5:7, is an exceedingly bitter herb used to describe the great bitterness caused by Israel’s lack of justice. (Also, see Amos 5:7 and Isaiah 5:20 to describe the behavior of calling evil good and good evil.)

It is important to note that Amos is written in a particular time and place. The book of Amos sets the words of Amos that he saw concerning Israel “in the days of King Uzziah of Judah and in the days of King Jeroboam son of Joash of Israel, two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1). There is thus something very specific about the litany of social justice infractions referenced in Amos 6 (see also Amos 4:1, 5:10–12, 8:4–7).

But there is also something profoundly universal about Amos’s diatribe against the super-rich who live in utter opulence, taking their privilege and self-indulgent lives for granted. Amos reveals that these riches are not just incidental and, as was also evident in last week’s lectionary reading (Amos 8:4–7), come at the cost of those who are already vulnerable to begin with.

An online search for who, most recently, has been drawn to this book steeped in the pursuit of justice and righteousness, is telling: Results show many scholars from the Developing World concerned about the state of their people in impoverished countries where the rich are getting richer and the poor poorer—for example, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Myanmar, and parts of Latin America. These countries feel in tangible ways the effects of neoliberal capitalism, imperialism, and globalization, with all the unfair labor practices and extraction of resources by the Global North, as well as the corruption and self-enrichment of leaders within their countries.

Amos offers an interesting case of being both an outsider and an insider. On the one hand, he is very much a Southerner from a small town in rural Tekoa, traveling north to deliver his message of judgment to the citizens of Samaria, the capital of the Northern Kingdom, which has been the beneficiary of a period of peace and prosperity. But Amos is not merely at odds with the urban elite of his northern neighbors; he also finds himself an outsider attacking the Jerusalem establishment and elite, who are similarly guilty of forcing subsistence farmers to produce surplus wealth for the benefit of the ruling class.

Amos could also be read against the backdrop of the imperial regimes of Assyria, Babylon, and Persia, which all traveled to distant lands to get their hands on precious goods to build their respective empires. There are some interesting parallels between the economic practices of the royal palaces that engaged in the economics of extracting resources from their subjects in both Samaria and Jerusalem, and this succession of empires that funded their numerous building projects and administrative bureaucracies by means of incessant plunder of neighboring lands.

Finally, Amos can also be viewed as an insider. After all, he is a landowner with a flock and income-generating fruit trees, so he also speaks from a position of privilege. Regardless, called by God to proclaim a different view of the world, Amos dares to speak to multiple audiences—in his context and in centuries to come—about the dangers of thinking privilege and riches are God-given rights. Rather, the message is that ivory beds and luxury goods, such as are on display in Amos 6, are fleeting, bringing to mind the wisdom of Matthew 6:19–21:

Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal, but store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

September 28, 2025