Commentary on Amos 6:1a, 4-7

When we think of the prophet Amos there is a tendency to emphasize the outsider nature of his prophetic calling.

Amos is a shepherd and a horticulturalist (a “herdsman and dresser of sycamore trees,” Amos 7:14), not a member of the prophetic families or guilds of Israel. There is, then, a disconnect, a jarring power and potential in his message delivered to the elite of the Northern kingdom. Abraham Joshua Heschel summarizes this approach beautifully:

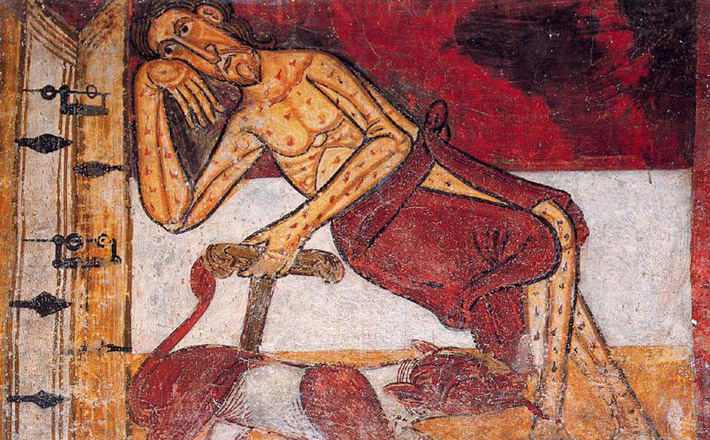

The rich had their summer and winter palaces adorned with costly ivory (3:15), gorgeous couches with damask pillows (3:12), on which they reclined at their sumptuous feasts. They planted vineyards, anointed themselves with previous oils (6:4-5; 5:11)…. At the same time there was no justice in the land (3:10), the poor were afflicted, exploited, even sold into slavery (2:6-8; 5:11), and the judges were corrupt (5:12). In the midst of this atmosphere arose Amos, a shepherd, to exclaim, “Woe to those that are at ease in Zion; and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria.”1

This is certainly a critical aspect of the prophecies of Amos, setting the context of his reported oracles of judgment; this is worth our attention as we preach on this text from Amos 6. And, perhaps, preachers themselves need to take this disconnect, this “outsider-in” tension more seriously than most, as we do tend to be (and often represent) the current insiders, the rich, the judges, the elite. But there is another aspect of the setting of this text, in the literary context of the Amos, that is equally, and perhaps even more telling.

Amos 5 ends with a warning that Israel will be taken “beyond Damascus” into exile (5:27), and this warning is declared by “the Lord, whose name is the God of hosts.” The partial reading for our lectionary of Amos 6 which follows (6:1a, 4-7) ends just before a similar oath is made by God. Amos 6:8 reads,

The Lord God has sworn by himself (says the Lord, the God of hosts):

I abhor the pride of Jacob

and hate his strongholds;

and I will deliver up the city and all that is in it.

This judgment is declared not just upon the unjust, unfair, intolerable religious and social deviances of the Northern Kingdom (centered on the mountain of Samaria, cf. 6:1a), but against Jerusalem itself, the center of the Southern Kingdom, and seat of the Temple. Notice that both before and after the reading from Amos 6, God swears by God’s own name; what is contained within the “bookends” of the divine name (5:27 — “the Lord [Yahweh], whose name is the God [Elohim] of hosts” and 6:8 — The Lord God (Adonay Yahweh) has sworn by himself [says the Lord (Yahweh), the God (Elohim) of hosts]) is the core of Amos’ critique of all the religious and social elite, not just the “backsliding” Northern Kingdom and its idolatry, but the Southern Kingdom as well, with its injustice.

Amos 6:4-7 has its sights set on the disconnect not between the shepherd/sycamore-dresser and the religious insiders, so much as between any and all who claim the Lord and yet live lives that are inconsistent with such a claim. These so-called believers are accused of singing idle songs, of drinking wine from bowls, and of anointing themselves with the finest oils (6:6-7). In and of themselves these things (singing, anointing, even drinking) are not the problem. In fact, in other places the term used here for improvisation on musical instruments is entirely positive, the reflection of a God-given ability (indeed Deuteronomy 31:1-11 highlights the gifts given, the “skill to all the skillful” that God imparts for the good of worship and the people).

The problem is not skillful song-singing, or celebration, or honoring those who may very well deserve to be honored; rather, it is that these practices are carried on even while the Titanic is sinking (see Amos 6:6b), and the people simply don’t care.

In a sense, Amos 6 is critiquing the social equivalent of the religious inconsistencies that he has criticized earlier (see Amos 5:21-24). The questions he might well be asking are questions such as, “How can we feast when there are those who have nothing to eat?” Or, “How can we anoint ourselves when the least among us have no honor?” Or, “How can we celebrate as the worlds of so many others are falling apart around them?” The answer should be obvious, Amos argues, but the peoples’ actions belie this. As Amos goes on to ask (rhetorically), “Do horses run on rocks? Does one plow the sea with oxen?” (6:12a). Such behavior, God declares through the prophet, is senseless, and this is exactly what the people are doing: “turning justice into poison, and the fruit of righteousness into wormwood” (6:12b).

In our own time we are, it seems to me, rich in targets for our sighting of Amos 6. We might point our homiletical fingers at the rich (the 1 percent), or at political figures or activist groups who betray themselves, or even at denominational institutions that sometimes fall prey to their humanness and fail to live up to our expectations and their own statements. But perhaps, in our own contexts as we seek to live out the calling to which God has called us, we ought first to invite those who hear us preach and teach this week to apply this text first to ourselves. Where do we live too much at ease, where do we miss the opportunity to meet the needs of a ruined or ruining “Joseph,” how might we live into right relationship with our neighbor and our world in the name of the God who has sworn to us by a Son?

1 Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Prophets (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2010), 27-28.

September 29, 2013