When folks complain to me about how violent the Old Testament is, I first like to remind them that a centerpiece of the New Testament—the crucifixion—is heinously violent. After that, I send them to the book of Acts. Acts is full of accounts of imprisonments, beatings, riots, stonings, and executions. People—especially Paul—are constantly being dragged around, sometimes left for dead.

Perhaps what makes the violence in Acts harder to notice is the matter-of-fact manner in which it is recounted. No one expects anything different from the Roman Empire; for the apostles, the violence of the empire was part of their everyday lives.

We still live in a world where violence is so frequent that it risks becoming banal, expected, unremarkable. That’s why I think the book of Acts presents for you, Working Preacher, an opportunity to startle your listeners out of their expectations, to show them a different way, a way of promise rather than cold calculation.

In today’s first lesson, Acts 16:16-34, it’s the jailer who longs for, and receives, an alternative vision of life in this world.

As our story opens Paul and Silas are being trailed around Philippi by a girl who cries out over and over, “These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation.” The girl herself is enslaved by people who are exploiting her for money, and when their money-making scheme is foiled by Paul and Silas, the enslavers lean on their status within the Roman Empire to sweep the apostles up into Rome’s criminal justice system.

The enslavers cloak their greed in a kind of pious civil religion; they hide their avarice behind accusations that Paul and Silas are agitators, outsiders, others—”These men are disturbing our city,” they say, “they are Jews.” Look at them, look at how they are not like us, look at what a threat they are to us. As Will Willimon writes of this passage, “If the nationalism and the anti-Semitism fail to work, we will throw in an appeal for old-time religion saying, ‘They advocate customs not lawful for us to practice.’ Nation, race, tradition—all stepping into line behind the dollar.”1

The girl’s enslavers—Paul and Silas’ accusers—have defined their own lives, and the lives of all those around them, according to their economic value. They see the imperial system, which thrives on violence, as a tool for their own advancement. They have a particular vision of life here on earth, one that we continue to see all around us even today—a way of life that leads with cynicism, distrust, and a sense that the system of exploitation that orders the world is inescapable. It’s in this world that the jailer comes onto the scene—just doing his job, another cog in the wheel of the empire.

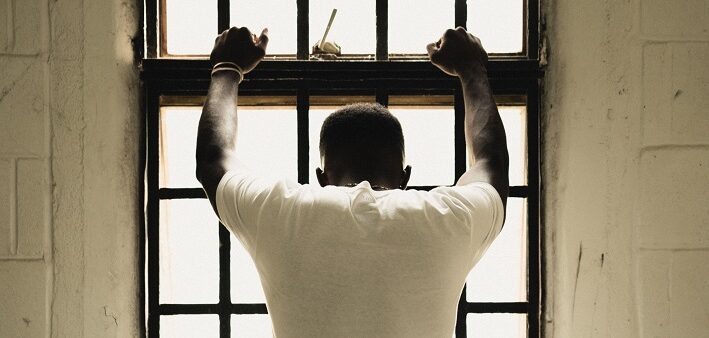

The jailer has received explicit orders from the magistrates to keep Paul and Silas securely, and so he has shackled them—naked and bloodied—in the innermost part of the prison. When, like something straight out of Hollywood, an earthquake breaks the chains of every prisoner there, the jailer senses doom, not from the prisoners themselves, but from his bosses in the imperial system. The jailer is doing a job for which failure means death. It will be the end of his worth in the eyes of the empire, and thus, he figures, will be the end of his life.

But then come Paul and Silas, who say, we do not play by the rules of this world. You are worth more than your work. You are a person who has value outside of your job, outside of any acknowledgment the imperial economic system gives to you. “Do not harm yourself; we are all here.” How extraordinary. By the rules of the empire, it’s every man for himself. But for Paul and Silas, it’s “we are all here.” We’re in this together. We see you, jailer, not as another cog in the wheels of Rome, but as a child of God, a person with value not because of anything you do, but just because you are.

The jailer is flabbergasted by this turn of events. The earthquake may have shaken the jail, but Paul and Silas’ compassion has shaken him. He is trembling, the text says, as he asks the apostles, “What must I do to be saved?” While this question, and Paul’s response, have been at the center of Christian theological discussions about salvation for centuries upon centuries, in the flow of the narrative, the jailer’s question is more immediate—what can I do to get out of this alive?

“Believe on the Lord Jesus, and you and your household will be saved.” “Saved”? Really? It seems to me belief in God’s saving work is what brings the danger to followers of Jesus in the book of Acts. And yet, for all of its dangers, the story of Paul and Silas shows us how life as a follower of Jesus is full of freedom and hope, unlike the life the world offers. We see this transformation in the jailer, who seeks to be saved from a world where his worth is defined by his job, where his value is determined by his utility for the empire, where the norm is to chase after money and power with little regard for human life. The jailer sees that Paul and Silas’ faith has brought them imprisonment and violence, but it has also released them from a cruel calculus that defines their value by what they can accomplish. In their great risk is also great promise.

What holds for the jailer and the apostles and the people in the pews also holds for you, Working Preacher. The life of a pastor is a called one, to be sure, but it is not the source of your worth in the world. Neither are your membership statistics or your stewardship totals or the views of your streaming worship service. You are beloved. Show the world what it means to live a life of promise, a life where “we are all here.”2

Cameron

Notes

- Will Willimon, Acts (Interpretation; Atlanta: John Knox, 1988), 139.

- This essay is adapted from a sermon the author delivered at Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, Minneapolis, on May 8, 2022.