This is one of those weeks when preachers find a text pretty easy to interpret but the sermon hard to deliver.

Ah, but it’s never easy to interpret a text, right? Especially parables. Those things rarely sit still. What’s even more troublesome: we churchpeople have long legacies of domesticating parables for our own comfort. Working Preachers, your job description this week includes counteracting histories of bad interpretation.

Think of all the sappy moralistic solutions that people concoct to protect themselves from the parables and their subversive ways of declaring the strange theo-logic of God’s good news. Those solutions try to keep these stories from utterly messing with our self-protective instincts and economic interests. The Good Samaritan becomes about being nice to needy people. The Mustard Seed becomes a paean to patient passivity. This week’s Rich Fool becomes a cute reminder that you never see U-Haul trailers behind hearses.

Push back, Working Preachers. Demand more. The tragic tale of the Rich Fool isn’t a reminder that we might die sooner than we hoped or that we might find ourselves wishing that we had spent more time at the kids’ basketball games and less at the office (although those are useful lessons from time to time). The parable digs deeper, toward the heart. It tells about money’s ability to impoverish your soul and rewire your values. The way the parable is explicitly framed (in Luke 12:15) makes it warn against greed, acquisitiveness, and egoistic preoccupation with one’s own security. It offers an explanation for why otherwise ordinary or hard-working people might end up existing in their own self-absorbed universes, constructing lives in which they don’t have to give a damn about anybody else, especially people they can’t see. Or don’t want to see.

What exactly does the parable explain? That greed is idolatry.

The man in the parable has chosen to live in a world of one.1 Speaking to himself about the pleasures he can enjoy, his words reveal that no one else matters to him. He is the epitome of a “me first” ideology and hoarded advantages. In addition, the man who prompts the parable in the first place, who petitions Jesus for help in getting part of the family inheritance, appears to be asking a respected spiritual leader to validate his own desire for wealth.

Greed shows its true identity as idolatry when Jesus says over and over again in Luke that we must beware of what money can do to us (see Luke 12:33-34; 16:13; note also Colossians 3:5, in this week’s second reading). Greed compels us to banish anyone who looks like they might threaten “what’s ours.” Likewise, idolatry constructs worldviews in which self-interest is the cardinal virtue. Idolatry lies, whispering that cupidity won’t erode my capacity for community. Idolatry makes fools of us all when it convinces us to create religious justifications for our arrogance and hardheartedness.

Contemporary examples of souls and values deformed by greed are not difficult to find.

Next comes the hard part: the sermon.

A sermon that will be faithful to a passage like this requires your courage, nuance, and forethought, working preachers. Courage, because we desperately need preachers who will call out idolatry. Nuance, because this parable is ready to speak to a range of audiences in 2019. Forethought, because contending with our idolatrous relationships to wealth and privilege requires ongoing attention.

Courageous preaching doesn’t apologize for what the Bible says but calls a congregation to a deeper engagement with the word of God. Courageous preaching doesn’t need to be acerbic preaching. Just tell the truth. Admit why the passage is challenging to you, too. Most important: remember that some people will experience what you say as liberating, even if it feels like you’re telling them what they don’t want to hear. After all, to identify and then reject idolatrous greed is to discover the possibility of being “rich toward God,” something Jesus discusses in more detail after the parable concludes (in next week’s gospel reading).

Nuance will help prevent you from veering into caricatures, such as labeling all wealthy people as reprobate or describing all profit-earning ventures as inherently exploitative. Sermons full of generalized accusations might rally the base, but they don’t change lives. Remember that greed corrupts the poor as easily as it does the rich (although the consequences are more confined). Remember that very spiritual people cling to idols, too. Remember that the passage applies not only to individuals, as if a sermon’s sole scope should be to identify exactly who in the room qualifies as “rich” and who does not. Consider in what ways your society or community is like the parable’s rich man. What do Jesus’ teachings mean when the populations of ten nations possess 79 percent of the world’s total wealth even though they constitute only 29 percent of the world’s total population? Use nuance, not to pass off Jesus’ warnings onto someone else or to indict a faceless “system,” but to extend his message into all the places it needs to go.

Forethought helps prevent the sermon from vanishing as soon as you exit the pulpit. How will your preaching invite people into asking “What should we do?” in response? How will you revisit the topic next Sunday, or farther down the road when additional Lukan texts will revisit questions of wealth, possessions, discipleship, and corrosive self-interest? Sermons about difficult topics should never be “one and done” events.

Care for yourself this week. Talk with colleagues. Keep time free in your calendar — both this week and especially during the days after the sermon when people might want to talk. Reflect on the idols from which Christ has delivered you and those to which you still cling. Follow the words of Colossians and “set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians 3:2-3).

Most of all, remember that God is rich and generous toward you and toward all those to whom you have been called to bring hard but good news.

Matt

Notes:

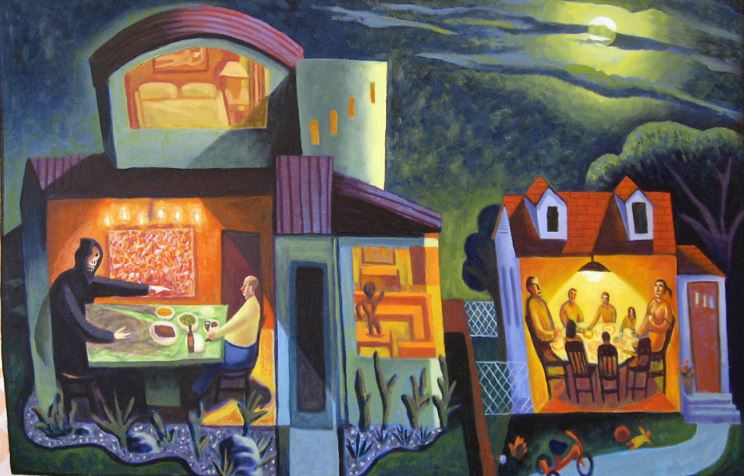

- I love how James B. Janknegt interprets the parable in his painting “Rich Fool.” The rich man dines and dies alone in a large house, which is furnished with a literally heartless piece of sculpture, while a family of eight enjoys one another’s company around a table in a more modest dwelling nearby.