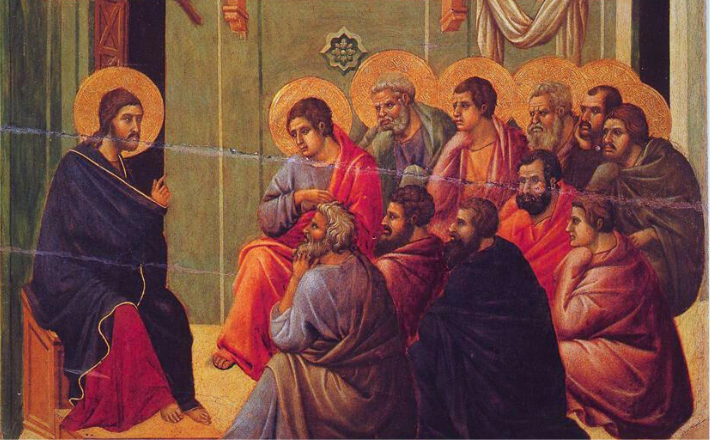

Commentary on Acts 1:15-17, 21-26

Amid all the joy and promise of Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, Judas remained a problem for Jesus’ movement. Though less well-known than Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter Sunday, Spy Wednesday—the day “Satan entered Judas called Iscariot, who was one of the twelve,” driving him to deliver Jesus up to malevolent temple authorities (Luke 22:1‒6)—also haunts Holy Week.

Along with injecting intrigue into the Passion story, the villainous secret agent Judas also engenders dissonance among faithful Christ confessors. It’s unsettling to accept that one of Jesus’ chosen confidants betrays him and facilitates his execution. A crisis of trust erupts. Can I trust you not to turn against Jesus? Can I even completely trust myself? (“Surely, not I [or is it]?” Mark 14:19). Couldn’t God or Jesus or another disciple have seen through Judas and stopped his nefarious scheme?

While the Passion narratives indicate that Jesus knew about Judas’s plot (and let it unfold), it remains uncertain how long he had suspected Judas and what all motivated his treachery: disappointment with Jesus’ nonviolent messianic strategy? cutting his losses as Jesus faces increasing opposition? While Judas accepts payment from the priestly authorities (Luke 22:5‒6; see also Acts 1:18), simple greed seems insufficient to account for his callous betrayal.

So, what to do about the Judas problem? Filling Judas’s vacated place among the 12 apostles is the first item of business taken up by Jesus’ followers after his departure. Amazingly, Peter takes the lead. Recall that Peter himself was no model of loyalty. As surely as Judas betrayed Jesus, Peter repeatedly disavowed all knowledge of Jesus at Jesus’ trial before the high priest (Luke 22:54‒62). Though not in league with Jesus’ adversaries, Peter was, in his own way, a co-agent of Satan with Judas (see 22:31, 34).

Yet their fates could not differ more starkly: Peter gets a second chance, a special appearance from the risen Christ (24:34), and reaffirmation of his leadership position (see also 22:31‒32); Judas dies horribly in disgrace (by bizarre disembowelment, according to Acts 1:18; by suicidal hanging in Matthew 27:5). No rehabilitation, no redemption for Judas—only replacement—supervised by the same Peter who thrice repudiated Jesus. This is yet another facet of the Judas problem the New Testament leaves hanging.

Peter attempts to explain the Judas affair via predestinarian logic, following Jesus’ pronouncement: “For the Son of Man is going as it has been determined, but woe to that one by whom he is betrayed!” (Luke 22:22). Woe be to poor Judas. Very sad indeed, but small comfort to Judas or thoughtful readers seeking a fuller explanation. Peter buttresses the deterministic plan with scriptural prophecy: “The scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Spirit foretold concerning Judas, who became a guide for those who arrested Jesus” (Acts 1:16). Luke believes that scripture “must” be fulfilled by all means “necessary” (see also 22:37; 24:26, 44; Acts 17:2‒3).

Peter stretches the point, however, in claiming that the poet-king David specifically addressed Judas’s case in two hymns: “For it is written in the book of Psalms, ‘Let his house become desolate, and let there be no one to live in it’ [Psalm 69:25]; and ‘Let another take his position of overseer’ [Psalm 109:8]” (Acts 1:16, 20). These are general references Peter cobbles together regarding the plight of anyone who attacks God’s righteous agents. Peter infers their application to Judas and interprets them to fit the present situation.

Thus develops the dynamic (not formulaic) practice of searching, probing, and processing the Jewish Scriptures to understand God’s work in Christ (see Acts 8:30‒35; 17:11), an engaging, rewarding—yet challenging—hermeneutical venture we continue today in all due diligence and humility.

If Peter’s appeal to Scripture provides a less-than-satisfying answer to why Judas betrayed Jesus, it offers sage guidance concerning what should be done to move forward. Judas did what he did (for whatever reasons). He brought terrible harm to Jesus, but it was not terminal. The crucified Jesus lives, and his work must go on through his Spirit-empowered emissaries (1:8). “Let another” veteran disciple “take [Judas’s] position” among the 12 and “become a witness with us to his resurrection” (1:21‒22). The temporarily broken apostolic circle must be quickly restored.

Judas’s loss marks a tragedy for himself as well as for Jesus and his movement. Judas had been “chosen” by Jesus (Luke 6:12‒15) and given a full “share [or lot, klēros] in this ministry” (Acts 1:17). What a grievous waste of opportunity and shirk of responsibility. But “shares” in God’s realm are not exclusive to any individual or group. They are held in communal trust, shareable in the commonwealth of Christ.

Though the 12 may appear to be (and sometimes aspire to be) a ruling oligarchy under Jesus’ Lordship, they are in fact a representative body of God’s whole people configured as 12 tribes of Israel. Thus, replacing the 12th apostle after Judas’s defection signals the restoration of the entire Jerusalem congregation (numbering “about one hundred twenty” [1:16], a multiple of 12) and Israelite realm (see also 1:6).

Peter and John have prominent roles in the early part of Acts, but the other 10 apostles—including Matthias, who fills Judas’s slot (1:26)—are never named beyond the first chapter. The Holy Spirit soon engulfs all believers, regardless of age, gender, and social class (2:1‒4, 17‒21). Outside the 12, Barnabas, Stephen, and Philip the evangelist (not apostle) emerge as key servant-ministers (diakonoi, 4:36‒37; 6:1‒8:40; 11:22‒26).

In due course, unnamed missionaries spread the gospel outside Jerusalem (11:19‒21), Saul/Paul is transformed from arch persecutor to chief proclaimer of Christ, and women like Tabitha, Lydia, Priscilla, and Philip’s four daughters become leaders, teachers, and prophets in local congregations (9:36‒42; 16:13‒15, 40; 18:2‒3, 18, 24‒26; 21:8‒9).

As for replacing Judas, the very process of nomination and selection stresses cooperative involvement by the apostles and assembly—with God! Peter moderates the meeting and guides the congregation to propose two candidates and pray together, “Lord, you know everyone’s heart. Show us which one of these you have chosen”—which God proceeds to do through the casting of lots (like throwing a die, 1:24‒26). An odd mechanism, to be sure, for such a significant election (never used again in the New Testament). But maybe not so strange considering the linguistic link between this “lot” (klēros) revealing Judas’s successor and the “share” (same term) of ministry lost by Judas.

That’s the main point of this incident and main purpose of the risen Christ’s community: restoration by cooperation, common (koinos) good enacted through shared (klēros) service.

May 12, 2024