Commentary on John 9:1-41

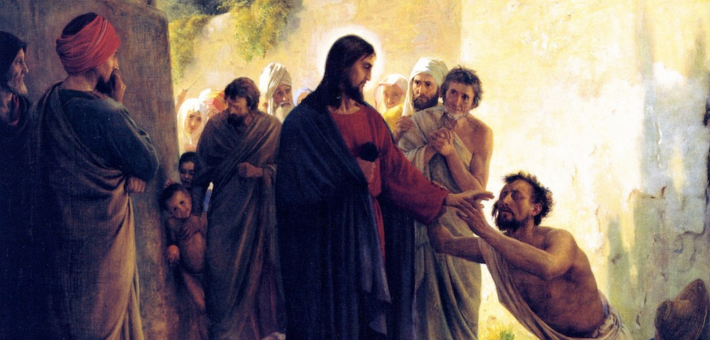

“Never since the world began has it been heard that anyone opened the eyes of a person born blind” (John 9:32).

Mixed reactions

This is a story about a healing, the Sabbath, and the interrogation it launches in the first century. The nature of the interrogation is to determine the identity of Jesus.

The length of the chapter entails numerous conversations with an unnamed man who has been healed. The Gospel account records many different reactions to the man’s condition. Initially, the disciples wish to instigate a theological debate using the man’s disability as an object lesson (9:2–5). Following the healing, the neighbors debate the man’s identity (9:8–12). Then, after an initial conversation with the healed man, the religious leaders offer their (mixed) theological assessments of the healer (9:13–17). Eventually, the man’s parents are summoned and acknowledge the man’s identity and testify to the origins of his visual impairment but fail to stake any claim on the nature of the healing (9:18–23). During a second interrogation of the man, the Pharisees fail to accept his testimony (9:24–34).

Within the fourth Gospel, the Pharisees are depicted as monitors of Jewish society, determining what is allowable in public life (see also 11:45–48). Today’s lectionary reading is indicative of this kind of scrutiny. Historically, the fourth Gospel overstates their influence. Public baptizing activity troubles them—whether from John the Baptist (1:24) or Jesus’s group (4:1). Sabbath activities are also part of their concern (9:13–16; see also 5:9–18).

By chapter 7, hearing of Jesus’s positive impact on some crowds, the Pharisees seek to arrest him (7:32). They remain antagonistic when their “temple police” fail to do so, implying that none of the leaders have been convinced (7:45–48). Even so, their concerns—shared with the chief priests—extend beyond jealousy: “If we let him go on like this … the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation” (11:48).

Their logic is evident: Jesus’s healings inspire the crowd’s trust, which, in turn, could draw Roman attention and trigger violence against Israel’s people and sacred spaces. If this is the case, the Pharisees’ concerns seem understandable. Authoritarian powers often shape local religious debates about proper public expressions of faith. By the end of chapter 11, the Pharisees have authorized a full search to arrest Jesus (11:57).

In our lectionary reading, the final scene of chapter 9 depicts a conversation between Jesus and the healed man. Although this is a second encounter between the two (see also 9:6–7), this time the unnamed man speaks, acknowledges Jesus’s divine identity, and “worships” him (9:35–38).

When Jesus restores a man’s sight in our lectionary text, the Pharisees briefly divide (9:16) but soon reunite in opposition: “Surely, we are not blind, are we?” (9:40). In the following chapter, the Jewish leadership (= “the Jews”) will divide again over the identity of Jesus, with an allusion back to the healing of chapter 9 from a segment more favorable toward Jesus: “These are not the words of one who has a demon. Can a demon open the eyes of the blind?” (10:21).

The complex causes of suffering

This is also a story that tackles the nature and origins of illness. The view in contemporary circles that personal suffering is directly associated with the (wrong) actions of individuals has a long religious tradition. Some ancient folk—including some of Jesus’s disciples—believed suffering was linked to unholy actions (“sin”). At times, Jesus seems to share this cultural, theological assumption. For example, in an earlier episode, when he found a man he had recently healed in the temple, he told him, “Do not sin any more, so that nothing worse happens to you” (5:14). Links between “sin” and “sickness” may also be implied elsewhere in the Gospel accounts (see Mark 2:1–12; Luke 13:10–17).

In today’s lectionary reading, however, Jesus problematizes that kind of theological thinking, offering a more complex analysis: “Neither this man nor his parents sinned.” Indeed, illnesses and infirmities may be due to other causes. Some may be due to natural causes; others, as in John 9, may be due to the possibility of divine intervention. And these interventions into our world may upset the religious constraints we—similar to the Pharisees of Jesus’s day (for example, Sabbath)—have put in place to hinder our ability to witness God’s faithful actions.

The healed man worships Jesus

Distinct from any other character within the narrative, this man whose sight was healed “worships” Jesus during his lifetime (9:38). The Greek word for the act of worship (proskuneō) could also be translated “to kneel (out of respect)” or “to prostrate oneself on the ground.” Yet, the reverence of worship in this scene makes sense, following the man’s public acknowledgment of Jesus’s status as “Lord.”

Earlier in the fourth Gospel, Jesus engages the unnamed Samaritan woman in a healthy, extensive conversation about “worship” (see 4:20–26). She labels Jesus a prophet (4:19), affirms her own belief in a coming Messiah (4:25), and even witnesses about this encounter to her fellow countrymen and -women (4:28–29), but never explicitly worships Jesus. That action is reserved for the healed man of chapter 9. Although several translations will utilize different English words for the Greek verb, “to worship” Jesus is a dominant theme of the Gospel of Matthew (see also 2:11; 8:2; 9:18; 14:33; 15:25; 20:20; 28:9; 28:17), but rare elsewhere among the canonical Gospels.

Implications for preaching

So what? What are the implications of this passage for preachers?

Reading this account during Lent reminds us of the human condition and the inability to discern divine intervention among us. Lent is an ecclesial opportunity to refocus the human lens and recognize all the ways God has acted among us, faithfully drawing us to God’s self. Sin, suffering, and healing can be reframed through the intervening presence of Jesus.

The passage directly distinguishes between spiritual needs and physical ailments individuals may have in our homes and in our communities. Our good God is not the author of these ailments but intervenes to sustain our broken, human bodies to draw us closer to God and to one another. Even those among us whose physical conditions may be failing are able to be the presence of God’s Spirit toward others in need.

May it be so!

March 15, 2026