Commentary on Luke 23:33-43

This is a martyr story.

It is important to know that. It might be a good idea to read six or eight other martyr stories, just to see what you should expect. Martyr stories are very serious about delivering what you should expect.

Martyrs die unjustly, and the storyteller makes sure you know that. The murderers of martyrs are clumsy, regretful (sometimes), and brutish, and the storytellers take great pains to demonstrate that, as well. Martyrs surprise their murderers, usually by speaking calmly and rationally and by refusing to scream in animal pain when they are tortured to death.

Martyrs never die before they speak words worth remembering, and that is true whether the martyr regrets having only one life to give for his country (Nathan Hale in the American rebellion against Britain) or insists, having lived an entire life devoted to the Sanctification of the Divine Name, he will not now abandon it (Eleazar in the Jewish rebellion against Antiochus IV Epiphanes, just before his tongue was cut out). Martyrs are calm.

And for that reason, the stories about martyrs are dangerous. I have watched as people approach death, tortured by disease. They can tell that the people waiting with them love martyr stories, and they know as well as anyone what is expected of them. Early on, they begin to practice saying things that will be worth remembering after they have died. This is a good practice, I think. Families sit with each other and remember together the dignity and honor and composure to which they have been trained as members of a strong family.

As the disease progresses and the pain becomes worse, you can see them struggle with it, partly because the pain is an unwelcome invader they are trying to fight off, partly because they find their strength decreasing just at the moment they need it all to fight the pain. They can tell that the people waiting with them would appreciate it if they could manage their last moments with a deep calm. If you have watched people in this sort of a struggle, you may well have seen how hard they work to make their death good for the people who are waiting with them. Sometimes it even works. And then, of course, there are the other times.

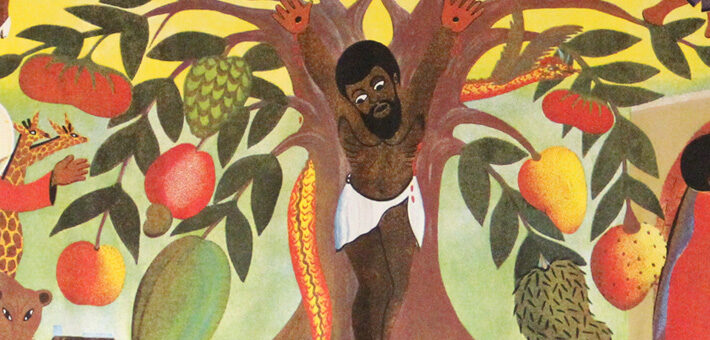

Luke tells a story of excruciating pain (the word comes from realistic memories of actual crucifixions), and he tells it with an enforced calm that makes of Jesus a Jewish martyr killed by Rome and its hired collaborators. Even as I recognize the dangers of imposing martyr-like calm on the chaos of torture, I still love Luke’s story. Though every one of us dies alone, Luke makes it clear that the Jewish family stays with Jesus all the way through. On the way to the torture site, the daughters of Jerusalem mourn for Jesus, claiming him as their brother, their son, as the grandson who reminded them of the hopes of their youth. “If this is what Rome does with wet wood,” says Jesus to his sister/grand/mothers, “shudder to think of the fire they will start when the wood is dry.” Luke’s audience saw that blaze when Rome set fire to the Temple in 70 CE.

When the torturers arrive at their chosen spot, horrifyingly named “Cranium,” the storyteller makes sure we notice the Jewish host (in Greek, laos, the word for faithful Israel) stands watching. Here, Luke uses the word theoreon, watching, for the activity of the host. The word implies they know exactly what they are looking at. They look and they understand: Rome is doing what Rome does, and Jews are doing what Jews do in response: they gather, they bear witness, now and in every century.

Everywhere you look in Luke’s gospel, Jesus finds himself surrounded by faithful, courageous Jews. At the Jordan when John is baptizing, even the tax collectors reveal themselves to be looking for God’s Kingdom and longing for Roman departure. Later in the story, Zacchaeus makes it clear that those tax collectors at the river were not alone in being faithful, and Luke’s Jesus calls him a “son of Abraham” in response.

And now on the hill of crucifixion, Jesus finds another faithful Jew, one who is crucified with him. To be sure, the other two victims are bandits, not messiahs, and to be sure, one of them taunts him with the same words used by Roman soldiers and hired collaborators: Messiah, King of the Jews. The other victim, however, knows that Jesus is a king and has a kingdom. These are things that, in Luke’s story, only faithful, expectant Jews know.

If the Romans are paying attention, they should commence worrying at this point. Crucifixion was torture intended to teach a political lesson: Rome can crush the humanity out of you. Remember that. But this crucifixion scene is loaded with Jews who cannot be crushed. This is trouble for oppressors. Rome should worry. The centurion who observes the death seems to have figured this out.

As the narrative camera pulls back, we discover Jesus is surrounded by mourners, followers, family, women and others who have also followed him, and observant Jews even from those among the Jewish Council. Everywhere Jesus turns there are people of faith. Years ago the comic, Woody Allen, said that eighty percent of life is showing up. Luke’s storyteller appears to know that. No matter what happens to the messiah, the King of the Jews, the Jewish family shows up.

Maybe this is what Luke means to suggest when he talks about expecting the Kingdom of God. Of course Luke (and Luke’s Jesus) expect the aeon of resurrection and restitution, but until that ultimate event actually takes place, it’s crucial that the people of the kingdom show up. They can show up to help, to repent, to wait, and to watch. They can show up to argue, to learn, to support, or to challenge. Sometimes they can only show up to beat their breasts and mourn. But they show up.

Perhaps when they show up, they pray the prayer Jesus taught them in Luke 11:

Father, hallowed be your name.

Your kingdom come.

Give us each day our daily bread.

And forgive us our sins,

for we ourselves forgive everyone indebted to us.

And do not bring us to the time of trial.

That seems a good prayer to pray while waiting with the King of the Jews.

November 24, 2013