Commentary on John 18:1—19:42

The irony inherent in the name given to this day — Good Friday — is palpable throughout John’s account of Jesus’ Passion.

Though no death of an innocent should be considered “good,” yet through the obedience of the beloved son, even to the point of death, God redeems humanity. While reading the whole of this lengthy passage with appropriate breaks for prayer, song, and meditation may be the best way to “preach” it, I will point those preachers who want to say a little more to what I would describe as the revelatory irony in several passages of John’s narrative.

I Am (He)

John’s Jesus is strikingly different than the one portrayed by his sibling evangelists, and nowhere is this more striking than in the garden. He is not afraid, nor does he pray for relief. This is the mission and destiny for which he has been born and so when Peter seeks to defend him by the sword, Jesus’ question is almost the opposite of the prayer recorded by Mark, Matthew and Luke. In John’s account, Jesus could not imagine saying, “if it be your will, remove this cup from me.” Rather, he boldly asks, “Am I not to drink the cup the Father has given me?” Or, in other words, “Bring it on.”

And they do. It is not just a few guards or temple police that come for Jesus, but an entire Roman cohort of 480 soldiers. And when they answer Jesus’ bold question, “Who are you looking for?” Jesus replies with the Greek form of the divine name, “I Am.” (We supply the “he” to make the sentence function grammatically.) In this declaration, Jesus is revealing an essential element of his identity — that he and the God of Israel are one. Little wonder, then, that at this pronouncement, the whole cohort is thrown to the ground. Though they have come to arrest Jesus with weapons they are powerless in his presence and, indeed and ironically, fall prostrate as if in worship. Jesus, it is clear, gives himself up by his own choice, just as he said we would back in John 10 — “I lay down my life — no one takes it from me — and I will take it up again” (John 10:17-18).

What Is Truth

Pilate is not a neutral figure in John. He asserts his authority over and against both Jesus and the religious authorities who accuse him by assigning Jesus the title “King of the Jews.” Only Caesar, after all, can crown a “king of the Jews,” reminding the religious authorities of who really exercises power in this affair. At the same time, he bends to their will and agrees to have Jesus crucified even as he declares Jesus’ innocence. Pilate is a complicated figure, trapped by forces larger than he can imagine. He sardonically — or is it wistfully? — asks, “What is truth?” in order to avoid the political gambit that has been laid in front of him.

Ironically, he is standing in the presence of truth embodied when he asks this question, and it is only because he lacks the courage to see and acknowledge this truth that he is doomed to ill-fated political machinations as he tries, and fails, to sit the fence. What is truth? That Jesus is, indeed, the king of the Jews and all the world, the one through whom God exercises a rule of “grace upon grace” (1:16) and in this way defeats not just the power of Caesar but of death itself.

Glory

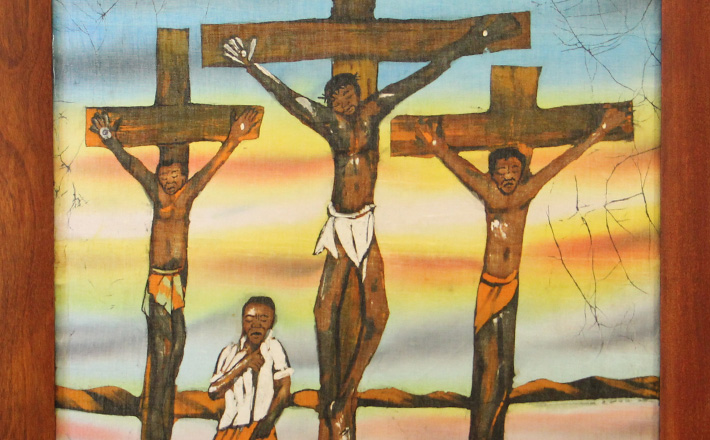

Jesus needs no help carrying his cross in John’s gospel. He knows this is the time where he will “draw all people to himself” (12:32). All that he does is therefore done in order to fulfill Scripture. Throughout John’s passion, the cross is not Jesus’ moment of humiliation, but rather of his glory. He reigns from the cross, issuing, for instance, an executive order that creates the first Christian family by uniting his mother to the disciple he loved. (This is a family born not of blood of the will of the flesh but from God (1:13), the first of a new humanity united in Christ.) Finally, near the end of the scene, when Jesus has fulfilled all that is required, he cries in victory, “It is finished.” Or, to borrow the common parlance, “mission accomplished.”

The great irony of John’s passion is that in Jesus we see God’s strength, majesty, and might revealed amid the pain and humiliation of crucifixion. While there is tremendous value in the more “human” portrayal of Jesus in Mark or the more compassionate Jesus in Luke, John’s depiction of the Passion of our Lord reminds us that, ultimately, Jesus is Lord. Through him God overcomes any and all obstacles — including death — in order to redeem and restore us. When we feel most vulnerable, most broken, most hopeless, it may be that John’s picture of Jesus will remind us of the promise that just as Jesus not simply survived but also conquered through his suffering and death, so also will we prevail, brought to abundant life through the sacrifice and triumph of the Good Shepherd.

A Note on Anti-Jewish Elements in John

When we listen to the passion according to John it is difficult not to wince at some of the references John makes to “the Jews” and to his characterization of Jews more generally. Some explanation of the circumstances of John’s gospel — written from and for a community suffering persecution and expulsion from the synagogue — is probably in order. It must be stressed, however, that what may have been understandable, if also regrettable, polemic in the first-century has had disastrous effects ever since, and Christians must therefore be the first to defend our Jewish brothers and sisters then or now against the charge that they crucified Christ.

For more on this, see Matt Skinner’s article on Working Preacher as well as the sources he cites.

April 22, 2011