Commentary on Isaiah 52:13—53:12

This “servant song” (with 42:1-7; 49:1-6; 50:4-9) has been the subject of much scholarly debate.

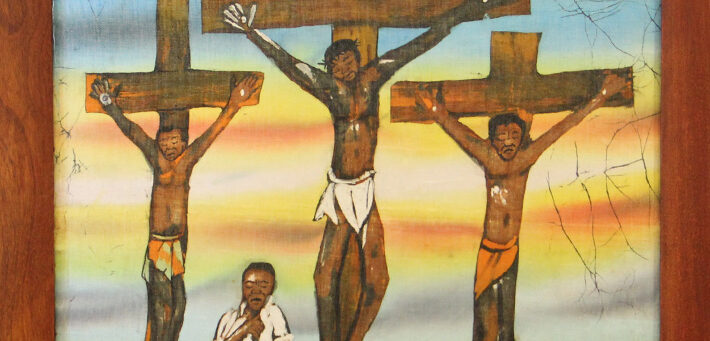

The suffering servant has been linked to Jesus since NT times, though direct references are uncommon (e.g., Matthew 8:17; Acts 8:32-35; I Peter 2:22) and the text refers primarily to past events. One interpretation among Jewish readers (and others) has been corporate (supported by Isaiah 41:8-9; 44:1-2; 48:20; 49:3), having reference to the hardships that Israel as a people (or remnant thereof) have endured and the redemptive effect. The apostle Paul uses these texts to refer to himself and his mission (Galatians 1:15; 2:2; 4:11; Romans 10:16; 15:21; Acts 13:47) and I Peter 2:21-25 commends the servant’s way to the Christian. Christians discern special connections to Jesus Christ, but the servant’s characteristics are open-ended enough to enable links to both individuals and communities that have suffered through the centuries.

The servant stands in the prophetic tradition (Moses, Jeremiah, Ezekiel). Their suffering is viewed in many texts in vocational terms, willingly taken up for the sake of the many, which is recognized by God as effective for new life in the world. In the servant songs, the suffering of the prophet is raised to a new key.

The main body of this text is 53:1-9, a confession by a community (note the “we”), probably Israel, on the suffering of the servant and their role therein. This is set within a framework of two speeches by God that honor the servant: 52:13-15; 53:10-12.

52:13-15 — God promises the ultimate exaltation of “my servant” before nations and kings. He has been cruelly disfigured and others look at him in numbed astonishment. The startled nations will finally see the significance of the servant and what he has done (see 49:7).

53:1-3 — To paraphrase verse 1: who would have believed that the arm (= power) of God would be revealed in such a suffering one? Suffering is God’s chief way of being powerful in the world! The speakers (“we”) concede that his origins are unremarkable, like a plant struggling for survival in an arid land. His appearance is like that of a leper; he suffers rejection by his own community; he is nothing to “write home about” (cf. Israel in Ezekiel 16:1-7). Pain and loneliness are his lot (cf. Job 19:13-19). The range of the suffering at the hands of others is amazing: despised, rejected, sorrowful, sick, assaulted, considered insignificant; verses 4-7 continue: afflicted, wounded, crushed, bruised, chastised, oppressed, unjustly accused.

53:4-9 — The speakers (like Job’s friends) thought he had been punished by God for something he did, when in fact they had caused his suffering. Remarkably, this suffering ends up making atonement for the very sins that produced it. The common Christian interpretation of his suffering as substitutionary is possible, but not likely. Sins “laid on him” (53:6) recall the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:20-22); the goat is not a substitute, but “bears on itself all their iniquities to a barren region.”On Israel’s behalf, the servant is “cut off from the land of the living” (53:8), “bearing their iniquities” (53:11), and “carrying the sin of many” (53:12). Like sheep the people have gone astray, but like the goat of Atonement Day, the lamb/servant bears their sins away into the wilderness, silently (see 42:2)

The “we” ceases at verse 7 and is replaced by a 3rd person account. The servant’s persecution and the false judgments of his work lead to death and the grave. He was sent to establish justice (42:4) and suffers a “perversion of justice” and, with the RSV, “Who gave [him] any regard?” (53:8). Moreover, he is given a dishonorable burial. The “tomb with the rich” may refer to wealth gained at the expense of others.

53:10-12 — The text ends on a note of promise; death does not have the last word. The servant will come to know what God has accomplished through him. The servant takes the sin into himself, “bearing their iniquities,” making many righteous. This is like the role of God in Isaiah 43:24-25, where the word translated “burden” comes from the same root as “servant.” What God does in Isaiah 43:24-25–bearing human sin, which leads to the unilateral declaration of forgiveness–is what the servant does in Isaiah 53. In Isaiah 43:24 God plays the role that the servant here assumes. In some sense, the servant is understood as an enfleshment of God and the effects of the servant’s work are spoken in terms that are normally ascribed to God (note the Spirit placed “upon” the servant in 42:1). But, even more, the servant is the vehicle for divine immanence; in and through the servant’s suffering, God suffers what is necessary to overcome the forces of evil.

What the servant has done is understood to be the will of God (53:10). That is, his sufferings are taken up and given a vocational understanding–suffering on behalf of others (cf. Mother Theresa). The phrase, “take up the cross,” must refer only to the sufferings that could be avoided (not all suffering should be so understood!). The servant’s “offspring” are those who follow his example and carry on his way of being for others in the world (see I Peter 2:21).

One haunting question: Why is suffering given such a prominent place in the divine economy for both OT and NT? Why do God, the suffering servant, and Jesus, the righteous one, suffer so? We may be helped by noting how the passion story draws especially on Psalms of lament (22, 31, 34, 35, 69) to express the plight of the righteous sufferer. These psalms and the servant songs (and other texts with suffering servant themes, such as Job and Jeremiah) show that it is nothing new or unusual for faithful followers of God to suffer. This is the shape of life needed to rid the world of suffering. Jesus stands in a long tradition of righteous ones, whose mission on behalf of life is carried forward in and through suffering. His followers are called to give a suffering shape to their daily lives for the sake of the life of others (I Peter 2:21).

April 22, 2011