Commentary on Hebrews 10:16-25

The book of Hebrews is often seen, not without reason, as one of the New Testament’s most difficult texts.

Students who have mastered much of New Testament Greek run aground on its rocky stylistic shoals. Its imagery may seem illogical — how can Jesus be both sacrifice and High Priest? And many Christian preachers find it hard to proclaim the messages of Hebrews without lapsing into supercessionism. Why, on Good Friday of all days, should we even attempt to make sense of what Hebrews has to say? Yet today’s lectionary text reflects on the central theme of the day in ways that help us think differently about the meaning of Christ’s sacrificial death.

While most commentators see a major section break between verses 18 and 19 (signaled by the “therefore” at the beginning of verse 19), the lectionary passage includes verses 16 through 18, thereby incorporating the quotation of Jeremiah 31 that is cited more fully in Hebrews 8:10-12. The theme of the “new covenant” was popular with early Christians who understood their scriptures to be fulfilled in the coming of Christ. Here, as often, the emphasis is on the interior nature of the covenant, laws placed in the hearts of believers and written on their minds. Omitting the middle section of the quotation brings the first and last pieces into a neat parallel: when God has written the law in believers’ minds, that they might remember it forever, then God will no longer remember their lawless and sinful deeds.

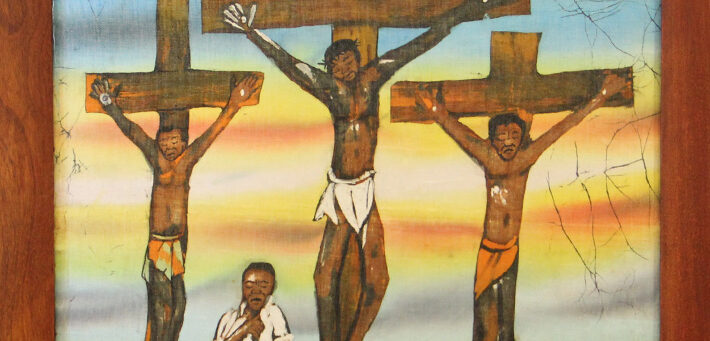

The previous section of Hebrews has developed a detailed argument based on the notion of Christ as the true and eternally effective sacrifice, and this is the image to which this passage returns. Those of us unaccustomed to sacrifice as a part of worship practice may be somewhat put off by references to Jesus’ “blood” and “flesh” as effecting access to God. Yet it is self-evident to the author of Hebrews, steeped in the sacrificial tradition of the Hebrew Bible, that any act that makes divine forgiveness of sin possible must necessarily entail the shedding of blood. As the previous section of Hebrews argues, Jesus’ shed blood means that no further cultic sacrificial practices are necessary. The blood sacrifice of Christ is perfect and permanently effective.

What is likely to prove more interesting to us about this passage is what the author claims Jesus’ sacrifice means to us. The Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) tradition of the high priest entering the holiest part of the sanctuary only once a year, and only after the most careful preparation, makes the “confidence” with which believers enter into the “sanctuary” an almost comic bravado. Who would dare do such a thing–except that the Christ event has changed everything?! This “confidence” also suggests boldness even in the face of opposition, a sense likely not lost on the first readers, who lived under the threat of persecution for their faith.

Most readers familiar with the Synoptic Gospels will likely read the reference to the “opened curtain” and “his flesh” as an allusion to the tradition of the Temple curtain being torn at Jesus’ death (cf. Matthew 27:51). Yet scholars suggest that this particular tradition may not have been known to the author of Hebrews. Rather, the reference to Jesus’ “flesh” in opening the curtain may emphasize that Christ did not provide believers access to God by some heavenly journey or spiritual act, but by the obedience that brought his physical body to its painful and humiliating death (as Philippians 2:8 says, “even death on a cross”). In the situation of persecution which the first readers of Hebrews faced, their discipleship might come to entail the same sort of physical suffering. For us, the reminder is that neither Jesus’ obedience nor ours is something that involves just our spiritual being. Our entire selves — physical, mental, spiritual, emotional–are involved in our Christian existence.

In certain ways, then, this text is a variation on the Christ-hymn of Philippians 2, transposed, as it were, into a different key. In contrast to the likely Gnostic beliefs of the writer’s opponents, who would have insisted that Christ’s spiritual being transcended his earthly, material body, the author insists that it is through Christ’s body — his broken flesh, his shed blood–that believers have access to the “new and living way” (verse 20). His sacrifice makes possible his exaltation to the “high priest[hood] over the house of God” (verse 21) and our participation in the house of God.

Christ’s sacrifice enables believers to have a “true heart” (cf. Isaiah 38:3) and to practice the virtues of faith, hope, and love, mentioned in verses 22, 23, and 24 successively. There is no reason to suppose that these virtues, mentioned in this order, are an allusion to Paul’s discussion of love in 1 Corinthians 13, although it is entirely possible that both stem from a very early Christian liturgical use of the triad. In any case, Hebrews understands these three to be intimately intertwined. Faith, the author will say in chapter 11, entails hope; love is the outward working of both.

Although the book of Hebrews rarely speaks in positive terms either of the physical body or of religious ritual, both come in for commendation in this passage. Just as Christ reaches his exaltation through his physical sacrifice, we approach God in our physical bodies, “washed” in the ritual of baptism. Moreover, while we do not engage in the ineffective ritual of repeated sacrifice, we are not therefore free to “do our own thing” religiously, to make our faith practice whatever we want it to be. Rather, the regular practice of corporate worship remains important, not only to engage in ritual but also to “encourag[e] one another” (verse 25). Hebrews is not particularly concerned with details of the Parousia, although the fact that God will one day bring about the End is an important part of the Christian confession. More important is the real, physical faith community, the locus of the faith, hope, and love that are products of the Christian life, made available to us through Jesus’ sacrifice.

April 22, 2011