Commentary on Daniel 7:9-10, 13-14

The selection of Daniel 7:9-10, 13-14 as a lectionary passage for the Feast of Christ the King reflects nearly two millennia of interpretation that identifies Jesus with the “one like a human being” in Daniel 7.

Jesus himself quotes this passage in Mark’s and Matthew’s gospels, foretelling that his disciples “‘will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Power’ and ‘coming with the clouds of heaven’” (Mark 14:62) and, in Matthew, that “all the tribes of the earth … will see ‘the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven’ with power and great glory” (Matthew 24:30). For Christian audiences, Jesus’s quotation and reinterpretation of Daniel 7:13-14 casts the passage in a Christological light. But to understand the significance of Jesus’s identification with the one like a human being in Daniel seven, it is necessary first to understand the passage in its earlier, Jewish context.

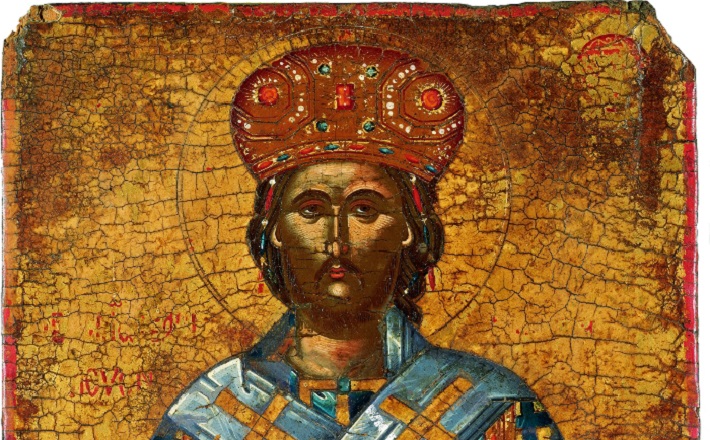

Daniel 7:9-10 and 13-14 shine a spotlight first on the kingship of God, who is portrayed in Daniel’s vision as “an Ancient One,” and second on the eternal kingship that is given to the one like a human being. Kingship and sovereignty are thus central themes in this passage. Heavenly kingship — and a heavenly kingdom — are not divorced from earthly kingship. The book of Daniel thematizes the relationship between earthly and heavenly rule, emphasizing that the sovereign authority of earthly kings depends upon the will of God (e.g., Daniel 2:21, 5:32).

Within the book of Daniel, these verses are part of a longer vision report that takes place toward the beginning of the reign of the fictional King Belshazzar (Daniel 7:1). The chronology provides context for Daniel’s vision. Through most of the book, years are reckoned according to the reigns of earthly kings. This way of reckoning time was common throughout the ancient Near East, and is found also in the biblical books of Kings and Chronicles. For the audience of Daniel, this system of dating calls attention to the historical reality that, after Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of Judah in 587 BCE (Daniel 1:1-2), Judah no longer had its own earthly king. Ruled instead by the Babylonian empire, Judeans were now subject to the whims of kings who neither respected their autonomy as a people nor recognized the power and authority of their God. The stories in Daniel portray the kings of Babylon commanding the worship of idols (chapter 3) and imagining themselves in the place of God (chapters 4, 6).

Readers learn at the conclusion of chapter 5 that the arrogant impiety of King Belshazzar prompts God to bring an end to Belshazzar’s kingship (Daniel 5:26-28). But Judeans still are not free. A new king, Darius the Mede, “receives the kingdom” immediately upon Belshazzar’s death (5:30). This narrative reflects the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus in 539 BCE. At this time, former subjects of the Babylonian Empire, including the Judeans in captivity and at home, became subjects of the Persian Empire.

Daniel’s vision in chapter seven reveals that, in time, yet another empire would follow that of Darius, and the Judean people would continue to suffer under foreign rule. The Macedonian general Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, including Judea, in 333-332 BCE. After his death, his successors fought to establish their own kingdoms. His generals Ptolemy and Seleukus each founded an empire, the Ptolemaic empire with its capital in Alexandria, Egypt, and the Seleukid Empire with its capitals in Seleukia in Mesopotamia and Antioch in Syria. Judeans were subject first to Ptolemaic rule, then to Seleukid rule.

Between the years 167 and 164 BCE, the Seleukid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes persecuted his Judean subjects, profaned the temple in Jerusalem, halted the regular sacrifices to YHWH, and established a Seleukid military garrison in Jerusalem. The biblical books Daniel and 1 and 2 Maccabees (the latter two books are considered part of the Apocrypha by Protestants and deuterocanonical by Catholics) provide our main literary sources for the persecution. They describe a program of state terror, murder, and enslavement and the outlawing of Jewish identity, scriptures, and worship.

Daniel seven received its final form during the persecution of Judean Jews by Antiochus IV Epiphanes. The vision of the one like a human being offered hope to Jews who had been subject to foreign rule for over four centuries and now were victims of state terror and persecution. Even as they saw their houses burned, their loved ones tortured and slaughtered, and their temple profaned by an “abomination that desolates” (Daniel 9:27, 11:31, 12:11), Daniel’s vision allowed them to see something else: the end of empires, the sovereign power of God, and their own future kingdom. The king who persecuted them would soon pass away. His kingdom, portrayed as a monstrous, mutated beast (7:7-8), would perish (7:11), just as the kingdoms before it had done (7:12). In its place God would establish a new and everlasting kingdom that would not pass away (7:14, 18, 27). It would be given not only to the one like a human being, but also “to the people of the holy ones of the Most High” (7:27).

The other kingdoms were characterized by violence, destruction, exploitation, and oppression. The final, eternal kingdom would be oriented toward justice (Daniel 7:10, 22, 26). It has its origin at the very throne of God.

In this week’s Gospel lection, Jesus declares, “my kingdom is not from this world” (John 18:36). It is from heaven. This statement describes its origin, not its scope. Do not imagine Christ’s kingship in abstraction from earthly politics. In the here and now, many still suffer political domination, state terror, and persecution. Others exercise authority and participate willingly in political systems. God gave sovereignty to this Human One in response to the evil perpetrated by empires and the suffering of God’s people. In so doing, God sought to free and empower the oppressed and inaugurate just rule on earth as in heaven.

November 22, 2015