Transforming the Nativity into a B-movie filled with monsters, magic, and hacked-off limbs might seem like little more than a master class in irreverence.

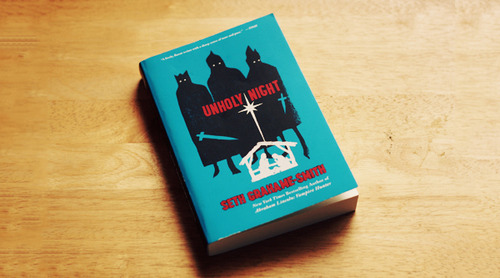

But in Unholy Night, Seth Grahame-Smith (author of Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) re-mythologizes the Nativity in a way that just might have relevance to preachers preparing for Advent and Christmas.

In Unholy Night, Grahame-Smith casts the wise men as three criminals on the run from Roman authorities in general and King Herod, a near-monster deformed by his desire for power, in particular. Leading the roughly hewn trio is Balthazar, better known as the Antioch Ghost, a charismatic most-wanted criminal of the Roman Empire.

The novel begins with a frenetic pace, only to slow momentarily when the three wise men, freshly freed from Herod’s dungeon, discover a terrified couple with a newborn who is the Son of God. When Herod’s troops invade the town, the criminals come (violently) to their aid (ergo the hacked-off limbs). The rest of the book largely chronicles the epic chase scene that ensues, as the family and their protectors flee to Egypt. Grahame-Smith’s introduction of other biblical characters — including a young and ambitious Pontius Pilate — helps drive the plot and keeps the book rooted in a slightly warped biblical narrative. Think the best chase scene ever told.

In an important sense, Grahame-Smith isn’t breaking new ground in this work. He follows a long-standing tradition in the church in imaginatively exploiting the brevity of biblical accounts of the Nativity, playing in those vague places in Matthew’s account that have long inspired (or is it tempted?) the creativity of the Church: Who exactly were the wise men? What happened during the flight to Egypt?

Yes, at times, Grahame-Smith takes great liberty in his telling, but he is reverent and orthodox (if a bit playful) when describing the Holy Family. Surprisingly, this grand and imaginative departure from anything resembling a historical-critical reading of Matthew’s nativity story is at times both deeply respectful of the Christian tradition and rebuffing to those Christians all-too-ready to sanitize the story through critical distance.

The contemporary church has often struggled to comment on the darkness inherent in the Nativity. The violence of the Empire, those systems of oppression that inhabit the corners of this cherished scene are often conspicuously absent from most preachers’ holiday musings. Grahame-Smith’s dark and twisted imagination reminds us Matthew was certainly more concerned about the monstrous proportions of Empire than he was constructing an accurate chronology or effectively communicating the architecture of a first-century stable.

Freed from the preacher’s fear of offending the Christmas-only crowd, Grahame-Smith is free to paint monsters as monsters. In this sense, his revisionist historical fiction tells a truth often lacking from our Christmas proclamation. In his apocalyptic prose, he vividly narrates the monstrous, sadistic darkness that is the backdrop for the light that has come into the world.

(Should this be that surprising from the author who identified Victorian norms as zombie-like, and slavery as vampiric?)

Of course Unholy Night is far from perfect. At times it becomes overly predictable, but what else could you do with a re-fashioning the world’s best-known story into a genre that is predictable by definition? It’s the mash-up that makes it fun, and fun it is. The embedded social commentary (intended or not) is often lost in the vividness of the world Grahame-Smith renders. And the violence is over-the-top — and made this reader bristle, but maybe that bristling is the point.

Whatever else it may be, Unholy Night could be an antidote — equal parts disturbing and healing — for those preachers caught in the malaise of having to think up one more creative Christmas sermon.