Commentary on 2 Corinthians 3:12—4:2

What is Paul up to in 2 Corinthians 3, one of the most challenging portions of all his letters?

Christian interpreters have for the most part ignored its difficulty by turning it into a rant against the presumed legalism and ceremonialism of Jews. Since the time of Eusebius (c. 260-341 CE) the two covenants work like this: the old covenant was a matter of local, specific, and temporally limited laws for the Jewish people, but the new covenant is universally applicable law. The thing to notice in this approach is that both covenants are considered to be law. The new law is better than the old, it is argued, because it can be applied to all people and in all times. Jesus, who advocates the law of love, is a better lawgiver than Moses. Now all of this is quite convenient for Eusebius, the architect of Christianity as the religion of empire after the conversion of Constantine (312). Empire needs universals as it erases the singularity, difference, and strangeness of each and every other. 2 Corinthians 3, twisted in Eusebius’ hands, fits this bill. We live with and repeat his misappropriation of this text to this day.

Yet perhaps there is a way to resist Eusebius. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335 – c. 395) had a wild idea about eternal progress and found biblical support for it in the phrase from “from glory into glory” in 2 Corinthians 3:18. Maybe this is a thread we can pull on to unravel the anti-Judaism later interpreters drew from the letter. By “progress” Gregory did not mean moral improvement. Rather, he took seriously the implication for spiritual life when God is regarded as truly infinite. Not very, very big, but beyond calculation. And not just beyond human calculation but any possible calculation. If God is infinite then our approach to God is, Gregory reasoned, experienced as a perpetual deferral of seeing or having God. Unlike Augustine (354-430), who sought God in order to rest in God, Gregory wrote about an unceasing, insatiable desire for God without rest and without end.

I am not unaware of how unsatisfying Gregory’s idea of perpetual deferral is for those of us whose Christianity rests in the Augustinian tradition. Siding with Gregory we would miss our beatific vision of God. Many of us have been quite looking forward to that. But Paul was not a Christian and not an Augustinian. In 2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2 there are other motifs of deferral in addition to “from glory into glory” and our chances of making sense in a non-Eusebius way of this text increases when we pay attention to them. One of them, I believe, is the motif of “face.” (See 2 Corinthians 1:11 2:10; 3:7,13,18; 4:6). Moses places a veil over his in 2 Corinthians 3:13. The veil comes off it in 3:16, which should be translated just as Paul quotes it from Exodus 34:34: “when he [Moses] turned to the Lord, the veil is taken away.” In 2 Corinthians 3:18 Paul has every face in his readership unveiled. If I can show that there is something infinite about the human (and divine) face, something that entails perpetual deferral, then the “new covenant” has a chance of being something other (and quite other) than the universal law of love.

Imagine a friend seated across the table. Her arched eyebrow, curled lip, darting eyes, and thousands of other movements on the page-like surface of her skin invite you to look upon her inner self. Her face seems to be put to use by her personality to give nonverbal expression to her thoughts and feelings. As a face reader you come to know your friend better by carefully observing all of the signs written on her face. Theoretically, then, if you gaze on her face forever you would know her perfectly.

Yet, there is something wrong about this version of face reading. Faces are indeed portals of the soul — and then again they aren’t. Why not? For one thing, as you gaze at your friend she gazes back at you, and in response to what you have read on her face your face changes, which she notices and changes her face, and so it goes with no end in sight. Now consider this also: when your eyes look into hers you see in her pupils your own reflection. So, now you have two faces to read instead of one, hers and yours, and since she now sees herself in your pupils her reading list has doubled. And so it goes ad infinitum. You friendship has become a hall of mirrors. Gazing at your friend across the table has resulted in more mystery not less, more desire to know her but the growing realization that you never will. Is this what 2 Corinthians 3:16 tells us Moses discovered? The more you look the more uncertain you become about who you are and who she is, about what she wants from you and what you must do to respond. Looking upon a face promises an unending search in which meaning, presence, and immediacy will always, as long as you gaze face to face, be deferred. In such a posture your non-satisfaction is guaranteed. That is the new covenant, always new.

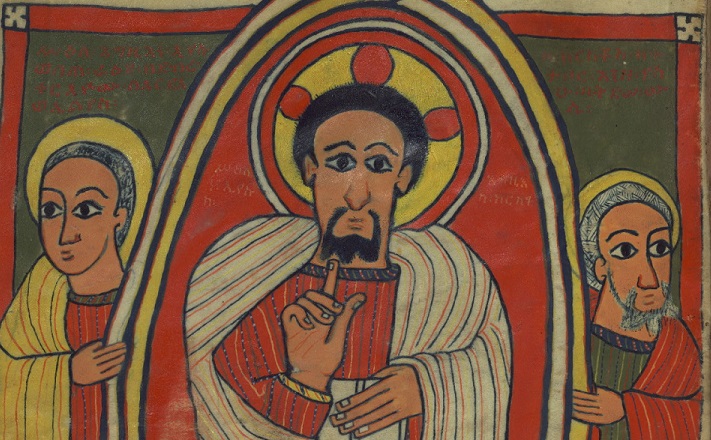

The new covenant is not another, better law. “New” and “law” really can’t be in the same sentence. If the new shows up deferral is laid to rest and it won’t take long for the new to become old. But “new” and “deferral” love each other greatly. In 2 Corinthians 3:18 Paul pictures the church as a community of faces gazing at one another lost in a hall of mirrors in a dizzying transfiguration into the image of Jesus, the Christ, the one who is to come, always deferred. From glory into glory …

February 7, 2016