Commentary on Philippians 2:5-11

Every year, the Sunday that begins Holy Week gives us this reading from Paul: “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus … ”

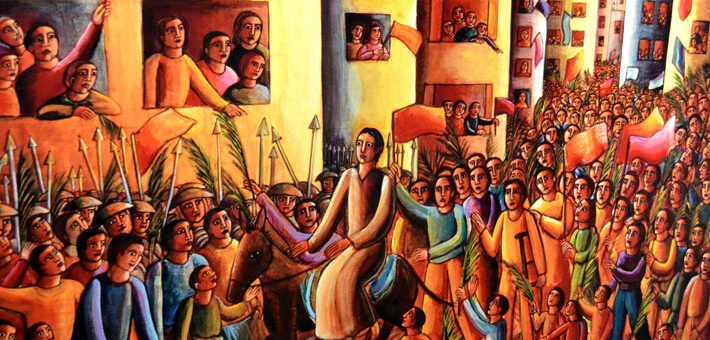

The brilliance and wisdom of Philippians 2:5-11 becomes especially poignant when the worship honors both the pageantry of the palm waving (Hurrah for Jesus!) and the darkness of the passion (Oh, sacred head … ) celebrated together on one day, for the admonition to live in the mind of Christ Jesus entails both adulation and sorrow. Entering into Holy Week — whose end will be both a tortured death and an awe-filled rising up out of the grave — with the words of this letter, opens the way for the people who have come to reckon with this mystery to know themselves as Christ-bearers: “Let the same mind be in you … ” How can we possibly imagine such a thing?

It is significant for answering that question to notice that every year of the Revised Common Lectionary (A, B, and C), we also hear from Isaiah the cries of the servant who is assaulted and aided: “I gave my back to those who struck me … The Lord God helps me … ” This image of the suffering servant beloved of YHWH is set next Paul’s meditation on Jesus’ suffering as an exhortation to the church of Philippi to welcome that humility for themselves. The readings culminate this year in the crucifixion story from the Gospel of Mark. We hear in that story, in yet more words about opposing realities: the laudatory cries of joy and the crowd shouting to “Crucify him!” We are given the opportunity to ponder these jarring truths.

This pondering, Paul reminds us, must take place in the context of our own present time, in our own lives, which, if we are attentive, show us that Jesus’ disciples and people of faith engaged in praise and scorn of him then, and that we persist, still today, in tolerating injustices all over the world. Jesus knew the sorrow of being intensely misunderstood — hailed while on his way to being killed. This is the lot of many people today — and also many animals, oceans, and plants.

This text is a judgment on two unbalanced expressions of the way of Christ: triumphalism (exultation over success — emphasizing the victory of resurrection) and excessive humility (emphasizing sin to the point of affected sentiment, obsequious self-abasement). The image of Christ is not simply one or the other. The image is not only an example of goodness to be imitated (Christ the judge), nor is it simply an image of taking charge as ruler (Christ the victor). The image does not give us either a pitiable loser or Superman. The image is both portraits because the story is true: the one sent to be our savior became empty in order to be given the highest name.

The question for us as individuals and as the church is this: How are we to live in Christ Jesus? As Fred Craddock puts it, the church is defined as “the in Christ Jesus mind.”1 The church is oriented by this admonition in several ways. First, it is the second person of the Trinity who stands in the center of our proclamation: “at the name of Jesus every knee should bend … ” We can gauge our bending and confession — our worship — on this basis. Is Jesus at the center? Or does another allegiance, even our difficulty in believing, play a larger role in what we do and say on Sunday?

Second, the verb for “was” in Philippians 2:5 isn’t really there in the Greek, making it unclear which verb to assume: “Let the same mind be in you that [was] [you have] in Christ Jesus … ” We may be exhorted to look back at Christ Jesus’ mind or we may possess the mind of Christ Jesus by virtue of our baptism. Another possibility is that we assume both translations would be accurate? The mind, the orientation, the way of being that was in Christ Jesus, is now in the body of Christ, the church. This is a startling assertion, and it compels us to measure up or at least interrogate our priorities. Churches and judicatories continually urge congregations to be “in mission,” to reach out, to advocate and care for the voiceless and powerless. If we do this outreach as persons who are manipulating the political realities of our age, is that the same manner of outreach that is meant to having the mind that was in Christ? This is what I mean by measuring. It is a plumb line, a yard stick, a means for holding a vision that can guide us as does the Good Shepherd’s rod and staff of Psalm 23. It is a measure, even, that can comfort us.

Finally, we are challenged by the humility of the one who emptied himself not to “lord it” over others even in the admonition from Paul that this highly exalted name deserves every tongue to confess it. As Christian history has repeatedly and shamefully shown, such honor easily turns into coercion and violence. We have enough of that in our world. The cry of this letter is for a unity among all people: “every knee should bend … ” But it is not the job of believers to fixate on making people of other faiths come over to “our side.” Rather, it is the highly exalted one who will, by God’s power, become known and welcomed. When the church takes God’s place, disaster follows.

Our world is not crying out for more intolerance but for greater mercy and loving kindness. We require a re-hearing of what has sounded like a charge to the church so that we hear in it the promise that in God’s time, in God’s reign (which is already here in our midst), there will be (and is!) unity of purpose and vision.

Notes:

1 Fred B. Craddock, Philippians (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1985), 43.

March 29, 2015