Commentary on Mark 14:1—15:47

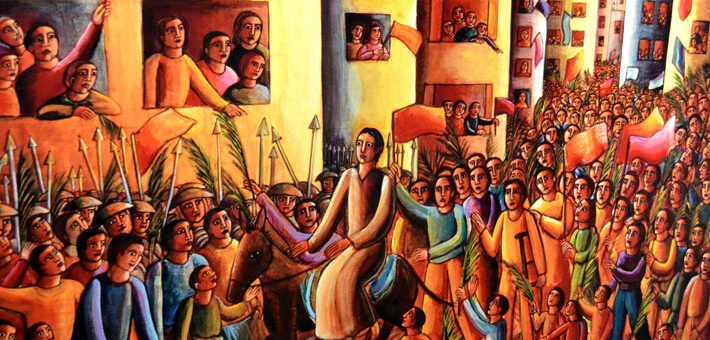

On the Sunday before Easter, the lectionary supplies readings for a liturgy of the palms, and readings for a liturgy of the passion.

In contexts where many do not participate in the liturgies of Holy Week, especially Good Friday, it is advisable to include the passion reading with its depiction of the crucifixion. This extended reading includes many important and rich episodes that are deserving of homiletical treatment. In this brief commentary, the focus will be on Mark’s testimony concerning the cause and meaning of Jesus’ death.

Mark does not supply a thorough and intellectually satisfying account of how the death of Jesus saves. Unlike some later interpreters, this gospel is not overly concerned with working out the technical details of how the death of Jesus figures in a divine transaction calculated to fix what is wrong with us. Furthermore, when reflection on the efficacy of the death of Jesus grows too abstract, strays too far from the particular stories that form the gospel witness, bad theology happens. Overly simplistic talk about God demanding the suffering of an innocent is dangerous talk for Christian communities that should be focused on breaking the patterns of abuse and oppression that devour the most vulnerable in our midst.

But a close reading of these chapters (and the broader biblical witness) does not support simplistic transactional understandings of the crucifixion as divinely sanctioned redemptive violence. A sermon that invites its hearers to imagine along with this story can help the community think and feel in a more nuanced way about the causes and meanings of the death of Jesus. This narrative invites the cooperative imagination into a space in which a subtle and realistic interplay of diverse causalities can be explored.

Why did Jesus die, according to Mark? Because of the failings of his closest followers. Judas betrayed him (Mark 14:10-11, 18, 43-45). His inner circle of disciples were too weak to keep awake and wait with him (Mark 14:32-42). Peter, despite his promises and protestations, denied him in his moment of trial (Mark 14:66-72). Mark even gives us the vivid image of an unknown young follower fleeing naked into the night from the scene of the arrest — his cowardice exposed for all to see (Mark 14:51-52). It is true that Jesus died because he was betrayed, deserted, and denied by his followers.

But that is not the whole story. Jesus died also because of the machinations of his enemies, both religious and secular. His ever-escalating conflict with the powerful reaches its endgame in these chapters. The chief priests and scribes look for an opportunity to kill him, and maneuver so as to avoid repercussions from the sympathetic crowd (Mark 14:1-2). His arrest under cover of darkness leads to a sham trial in the high priest’s courtyard (Mark 14:59). In the morning, an audience with Pilate proves that empire is more interested in keeping the Pax Romana than pursuing justice (Mark 15:15). It is true that Jesus died because his message and his way of being provoked powerful enemies.

But that is not the whole story. He died also because of his own self-giving love. On one level, a gospel account that begins with a breathless piling up of stories about the remarkable agency of its protagonist — with healings, feedings, exorcisms, and authoritative teachings unfolding “immediately” one upon another — concludes in a very different way. In these chapters, he is depicted as a passive victim placed under arrest, mocked, beaten and impaled. Yet, in the final analysis, Mark is clear that Jesus’ life was not taken from him, but given by him. This is shown in ways subtle (Mark 15:5, his choice of silence is a source of amazement), symbolic (Mark 14:22-25, his offering of bread and wine signifies his offering of his own body and blood to his followers), and explicit (Mark 10:45, in which he speaks of “giving his life”). It is true that Jesus died because he chose to give his life for others.

But even that is not the whole story. For it is the testimony of this witness that behind, and beneath, and through these many causes, there was also the inscrutable and deeply troubling will of God. We read it in the grammatically elusive dei (“must”) of the first passion prediction (Mark 8:31). We see its trace in the rending of the temple curtain at the moment of death (Mark 15:38). And most of all we overhear it in the tortured Gethsemane conversation between the reluctant but trusting Son, and the One he dared to call “Abba” (Mark 14:35-36). In that grief-stricken garden scene, especially, we confront the crucial claim that Jesus submitted his own will to God’s, breaking down in that moment our carefully constructed distinction between the cause which is his self-giving love, and the cause which is God’s mysterious will.

Mark’s passion story is less an argument to be understood, and more a theological poem to ponder. Held within its thrall, we are reminded again that those who claim to follow Jesus are capable of betrayal; we are educated about the paranoid violence of empire; we are warned about the dangers of self-interest among the professionally religious. But most of all we are fascinated by a particular man who, when push comes to shove, refuses to withdraw the high-stakes wager which is his whole self completely surrendered to that new way of being he called the Kingdom of God. Hoping against hope, he risks it all. If such risk is met by abandonment (Mark 15:34), then all is lost; but if by vindication (Mark 15:39), then all is gained. The passion narrative is not a doctrine to be dissected, but a drama to be experienced and explored again and again by those who would dare conform their own lives to the courageous, winsome, and faithful identity it discloses.

March 29, 2015