Commentary on John 8:31-36

What is truth? This question, posed by Pilate in his discussions with Jesus before having him crucified (John 18:38), is no less relevant today than when the Gospel of John was written. Around the world, we find populations divided into separate media-crafted realities, from the last election in the United States to the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Christians are equally divided, marshaling scripture to advance Christian nationalism from Washington, DC, to Moscow, with religious transpositions in Tel Aviv, Gaza, and a divided Jerusalem.

This week’s passage, touching on truth and freedom, is as politically and religiously fraught as modern debates today, and the passage as a whole has all the vitriol of a social media flame war, culminating in an attempt to kill Jesus. Literary context shapes the meaning of this lectionary passage, and this section concludes a series of teachings, debates, and conflicts in John 7:1–8:59 involving Jesus’ brothers, the Pharisees, chief priests, temple police, crowds, and “Judeans” (Ioudaioi). (Since all groups involved here are Jews, yet representing distinct and opposing postures/positions, Ioudaioi is best translated here as “Judeans,” rather than “Jews” as found in the New Revised Standard Version and New International Version.)

In terms of sacred time, this debate (see also 7:2) happens during the Festival of Booths, or Sukkot (see also Leviticus 23), commemorating the ancient Hebrews’ liminal period of sojourning in the desert after liberation from Egypt but before the conquest of the promised land—an ancient theme especially relevant during this period of Roman occupation, giving the debates over whether Jesus is the anointed king (Messiah) or the prophet who will liberate them from Rome a charged urgency (see also 6:15; 7:40–44). In terms of setting, these debates take place in the sacred space of the temple (John 7:14, 28; 8:20, 59), the epicenter of social, political, economic (8:20), and religious power in ancient Judea.

Historical context also shapes the meaning of our passage. Most scholars believe that John was composed sometime between 70 and 135 CE, the dates marking the first and last wars between Judea and Rome. Living in the rubble (literal, social, political, and theological) of the destruction of Herod’s temple in 70 CE and hurtling toward the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of Jews that resulted from the end of the Bar Kochba revolt in 135 CE, John’s Gospel finds itself enmeshed in the turbulence and tumult of the interwar period. For orientation and guidance, it returns to the story of Jesus in Judea to chart the way forward, tailoring its narrative to speak to the issues of its time.

In the memories of John’s readers, Sukkot was frequently a time of violence,1 ranging from the uprisings associated with the Hasmonean takeover of the high priesthood,2 to Herod’s murder of the high priest,3 to the beginnings of the first war with Rome,4 among other events. One can imagine memories of this violence being as fresh in the minds of John’s readers as 9/11 and October 7 are for many readers today. Thus, sacred time, space, and recent history align here to invest these debates with supreme existential importance. The key issue of “What is our character as the people of God?” saturates this passage.

Here, the immediate interlocutors are “the Judeans who believed in [Jesus]” (8:31), a characterization that is both surprising and confusing. Attention to the social dynamics in John 7:1–8:59 is crucial to identifying Jesus’ interlocutors in this passage, especially vis-à-vis the other Jewish groups mentioned and their differing postures toward Roman rule. While these Judeans seem united with Jesus in their opposition both to Roman hegemony (“we have never been slaves to anyone”; 8:33) and to Rome’s chief priestly collaborators (who affirm, “We have no king but the emperor”; 19:15), the debate that follows reveals sharp differences both in what they stand for and in how they think true freedom is to be achieved.

Jesus here stages an epistemic intervention, a disruption of constructions of reality that are wedded to social domination and militaristic violence. Implicit in Jesus’ claim that “you will know the truth, and the truth will make you free” (8:32) is an interrogation of the imperial “truth” that the gods have given Rome to rule the heavens and the earth,5 the revolutionary “truth” that liberation from the perceived slavery of Roman rule requires armed violence (for example, the Judeans clamor for the insurrectionist Barabbas; 18:40), and the deeper shared “truths” about the nature of power and the deceptions of redemptive violence.

In response, these Judeans prioritize their ethnic allegiance (“We are descendants of Abraham”) as the basis of their freedom (8:33; see also 8:39). Jesus affirms their shared ethnic identity (“I know that you are descendents of Abraham”; 8:37), but points to their embrace of violence as the enslaving sin that distinguishes his path of freedom from theirs (“Yet you look for an opportunity to kill me, because there is no place in you for my word”; 8:36–37])—a violence that has its origins in murderous evil itself (8:44) and stands contrary to Jesus’ way of life (8:51).

In this debate over the character of the God of Abraham, Jesus stands firm in what he has heard in the presence of the Father and exhorts these Judean followers to do likewise (8:38), but to no avail, as the pericope ends with an attempt to stone Jesus—the prescribed punishment for one perceived as blaspheming the Lord’s name (Leviticus 24:16), which Jesus invoked in 8:58.

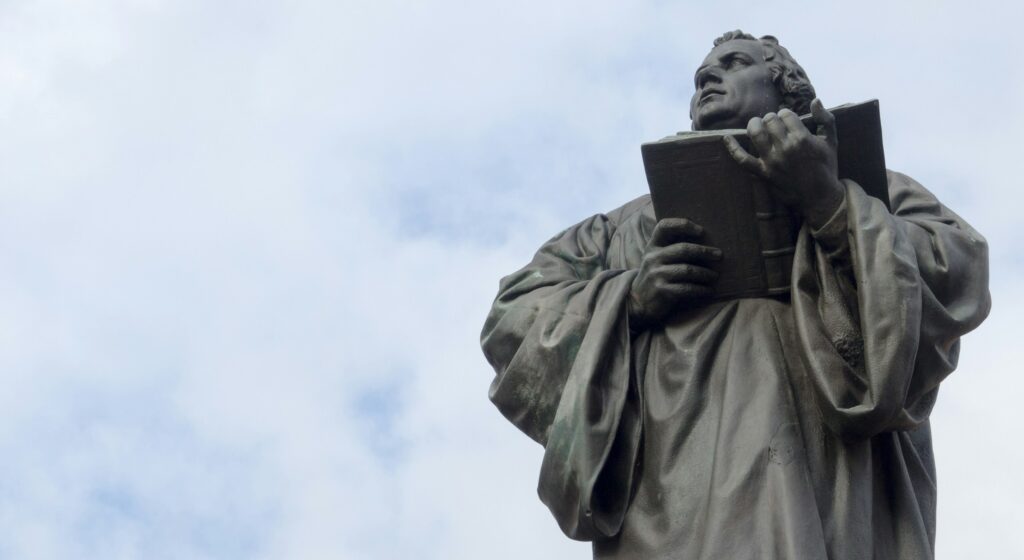

This text and conflicted debate is an apt selection for Reformation Sunday, as it speaks directly and forcefully to the need for ongoing reformation—indeed, transformation—of the peoples of God and descendants of Abraham. The ongoing (ab)use of this pericope to justify Christian violence against Jews, from Martin Luther’s “On the Jews and Their Lies” to the murderer in the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh (October 27, 2018), points to the pressing urgency today of Jesus’ prophetic, nonviolent resistance and his sharp critique of the slavery to violence and ethno-religious nationalism, even when biblically based. Will we finally find a place in us for his word (8:37)?

Notes

- See G. J. Goldberg, “The Festival of Sukkot in the Works of Josephus,” https://josephus.org/Sukkot.htm.

- Josephus, Antiquities 13.2.3 46; 13.13.5 372.

- Antiquities 15.3.3 50.

- War 2.19.1 515.

- Virgil, Aeneid 1.258–296.

October 26, 2025