Commentary on Luke 19:1-10

The story of Zacchaeus is a natural favorite for preachers and Sunday school teachers alike. When I teach the text, I ask students or congregants if they grew up singing about Zacchaeus. Sure enough, a few folks will begin singing, “Zacchaeus was a wee little man…” And others will join in as the song continues with Jesus’ words: “‘Zacchaeus, come down, for I’m going to your house today!’”

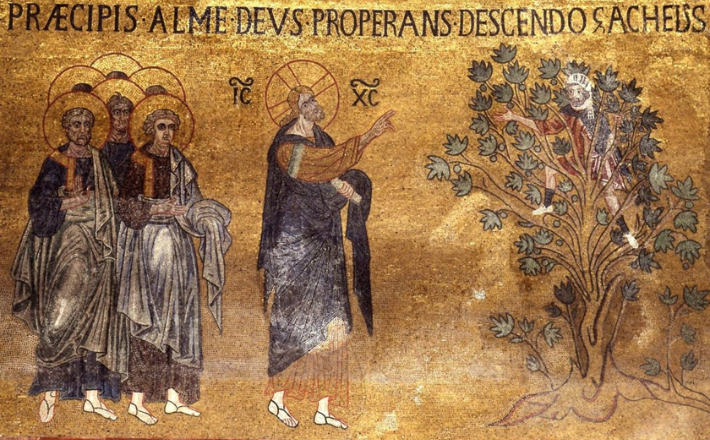

The little narrative details make the story particularly memorable, relatable, retellable: Short Zacchaeus. The sycamore tree he climbed. The surprise of the change of his ways. Here we have a character who enters the narrative as a villain and ends as a new man, a loving neighbor to those he previously mistreated.

Luke’s initial description of Zacchaeus prepares the reader to encounter precisely such a villain in need of conversion. With three initial descriptors, the dynamics of his character are told. First, he is not just a tax collector but a chief tax collector (the Greek here is arkitelõnēs). He is part of the imperial administrative chain that represents the power of Rome to control the livelihoods of the locals of Jericho. Second, he is rich. Luke’s narrative has already cast doubt on the faithfulness of the wealthy. Think, for instance, of Mary’s song prophesying that God “sent the rich away empty” (1:53). Moreover, the assumption nurtured here is that tax collectors only attain wealth by abusing their neighbors.

The last designation is about Zacchaeus’s diminutive stature. According to Mikeal Parsons, ancient ideas about various kinds of embodiment and the way they reflect the value of people would have nurtured in the reader an assumption that a short Zacchaeus was worthy of ridicule and exclusion: “What is the rhetorical effect on the authorial audience? Luke has spared no insulting image to paint Zacchaeus as a pathetic, even despicable character. The image of a traitorous, small-minded, greedy, physically diminutive tax collector is derisive and mocking.”[1]

If such is the image of Zacchaeus as we begin, his transformation is dramatic. At the end, he gives away half of his possessions and pays back those he has wronged. In so changing, he becomes “a son of Abraham” at long last, rather than a slave to empire and greed. He was once lost but has now been found. For preachers, then, this is a story meant to be imitated by all who have strayed far from the path of righteousness. Jesus has called him and us to repentance and the walk of repair.

This powerful narrative, however, contains other, perhaps even more powerful exegetical and homiletical possibilities.

First, as Isaac Soon has recently argued, the grammar of the Greek text leaves some ambiguity as to who exactly is the short person in the narrative.[2] Is the “he” who was “short in stature” Zacchaeus or Jesus? While I think the grammatical and narrative context points to Zacchaeus, Soon entertains the real possibility that Luke imagines a short savior. No matter what conclusion the preacher might reach, Soon’s argument is a vivid reminder that these stories, as familiar as they may seem, still contain exegetical possibilities we do not entertain often enough. Moreover, there is an opportunity to invite congregations to test their assumptions about Jesus, even what he looked like. We can test our assumptions about what it takes for Jesus to deliver us.

Second, as Joel Green has argued in his commentary, Zacchaeus may not be the villain so many have assumed he is.[3] When Zacchaeus speaks in verse 8, he may not be naming his future plans but his regular practice. Green notes that the tenses of the Greek verbs translated “I will give” and “I will pay back” are present-tense verbs. Greek tenses are flexible, so the typical translation is not incorrect, but an alternative translation is quite possible. Zacchaeus may be reporting his regular practice: I give to the poor, and I pay back when I have fallen short of my duties.

Thus, the ending of the story is not about a conversion of an individual but a shift in how he is perceived by his neighbors and the reader alike. He is not the rich chief tax collector we all assumed he was. He, too, is a son of Abraham. Even the tax collector belongs. Even Zacchaeus has a place.

And thus, the “lost” whom Jesus has come to save is not just a Zacchaeus excluded and marginalized because of communal perceptions of his wealth and profession, but a whole community fractured by his absence. That is, it is not just Zacchaeus who is delivered, but his household and the whole of Jericho as well.

So, the homiletical opportunities to help a congregation think broadly about the shape of salvation are rich with this passage. Rather than individualizing God’s deliverance, we can imagine its communal dimensions. Rather than pointing the finger at those “sinners” who do not belong, we might imagine the transformation to which God is calling us, the supposed insiders. Rather than boiling down salvation to a deferred gift of eternal life, we might imagine resurrection as a daily, tangible, communal transformation that can reshape our sense of who belongs, that will teach us anew that God’s grace is always more expansive than we have previously imagined.

Notes

- Mikeal C. Parsons, “‘Short in Stature’: Luke’s Physical Description of Zacchaeus,” NTS 47 (2001): 55.

- Isaac T. Soon, “The Little Messiah: Jesus as τῇ ἡλικίᾳ μικρός in Luke 19:3,” JBL 142 (2023): 151–70.

- See Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, New International Commentary on the New Testament (Eerdmans, 1997), 666–73.

November 2, 2025