Commentary on Romans 13:8-14

This passage, part of the larger section of Romans 12-15, has traditionally been called the ethical outworking of Paul’s presentation of the gospel in Romans 1-11, or the paraenesis section.

Unfortunately, this way of reading this section can be played out in a way that the ethic becomes secondary to, or not intimately of, a piece with the gospel message proper. The interweaving of proclamation and paranaesis — or “indicative” (stating the facts) and “imperative” (exhorting actions in response) — that occur throughout 1 Corinthians and Philippians, as well as the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, suggest that things may be more complicated than this.

Some scholars (myself included), view this section of Romans as part of the purpose of the extended and very contextually sensitive argument of Romans. Remember, Romans as a whole is not the presentation of the gospel, but rather a selective and contextual argument rooted in the good news for the purpose of exhortation to live a life that reflects the reconciliation effected by the incarnate God in Christ.

What does this mean? The proclamation of the good news of Jesus Christ must land somewhere in real space and time. It cannot remain in the theological stratosphere.

This also means that Christians in first-century Rome (and today) must clearly and directly manifest the good news in a way that is contextually relevant, as modeled by Paul throughout this particular letter.

This week’s reading is framed by the guiding exhortation to owe nothing but love in verse 8, and the statement in verse 14 to be clothed in Jesus Christ and to not indulge selfish desires. Immediately we are faced with the very other-centered nature of love defined by the cross.

It is important here to have some understanding of first-century Roman culture. Language of obligation defined the livelihood of Roman citizens in many spheres of life. To the emperor they “owed” honor and allegiance; to their benefactor (if they had one, and many likely did), they owed also money, possessions, honor; slaves owed service and their very lives; wives owed submission, and so on. It is worth inquiring where and how “obligation” culture works in the present day.

When Paul exhorts his audience to “owe” nothing except love, he is in a sense reconfiguring the arrangement of the furniture. To owe nothing except love eliminates the structures inherent in the ethic of the Roman cultural narrative. If obligation was related to position and to upholding status, authority, or certain relational dynamics, Paul’s exhortation to owe nothing except love forces some rethinking.

Importantly, Paul does not say, “In addition to your normal ethic based on our cultural system, love one another.” He says owe nothing. Suddenly the culturally derived conceptions of obligation and what they engender are relativized and even dismissed as irrelevant in light of the obligation of love to one another.

In a sense, then, these verses provide something of a contrast to or perhaps an overriding framework for understanding 13:1-7. While certain cultural or civic obligations cannot be dismissed, ultimately, the transformation of the mind and offering of the body, being clothed with Christ, is to rearrange the mental furniture of those in Christ from what they had known. It is to owe nothing, and live differently than what they’ve known, to adopt a new pattern and ethic.

This is the transformation of the mind Paul writes about in Romans 12:1-2; it is the way they are to give witness to the life that has died to sin and participates in the life of the Spirit as Paul writes in Romans 6-8; it is the life that walks according to the faith of Abraham in Romans 4; it is the life that judges not the brother or sister as Paul writes about in Romans 2.

To owe nothing but love to one another is to own the reality that we all are completely dependent on God’s grace for not only our forgiveness, but for our very existence, and it reframes how we live in relation to one another in our everyday interactions. It reframes it in such a way that other obligations become significantly less reality shaping than they once were.

Importantly, Paul emphasizes that love “fulfills the law” (verse 10). This is crucial in Romans, as the law plays center stage in much of the letter (Romans 2, 7, 10:4). Law introduced not only obligation to performance (“to keep the law”), but law also undergirded obligation culture, creating distinctions while operating on the basis of the distinctions it created.

By placing the fulfillment of the law in the context of reframing ideas of obligation, Paul takes another step in pulling the rug out from how law was used in that time and place. Fulfilling the law is being obligated to love of one another, rather than obligated to performance resulting in drawing lines of distinction between Jew and Gentile, male and female, slave and free, benefactor and beneficiary.

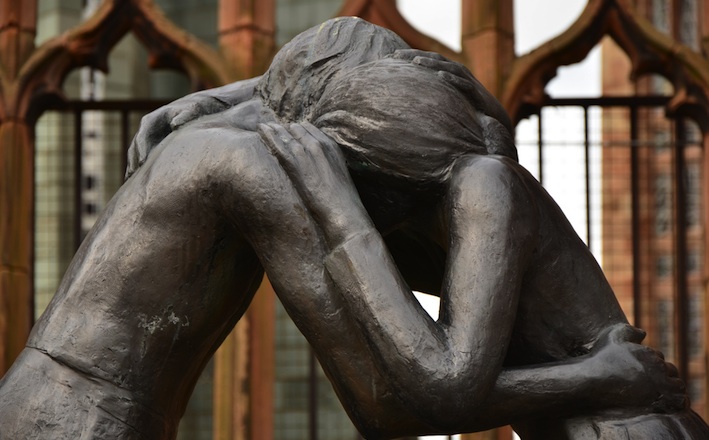

Love of one another, understood through the lens of the cross, means giving up our claims to ourselves and our claims over others, however they might seem “right” and “just” according to our own cultural narratives. This not only recalibrates obligation culture, but it recalibrates how the law — the foundation of obligation culture and the foundation of life — should be understood. “I have been crucified with Christ…”

Paul invites his audience to live in the present the eschatological life made possible through the cross and the work of the Spirit present among them. The exhortation is not unlike that of Jesus in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount, that the church live as “light” — “let your [plural!] light shine thusly: that people would see your good works and give glory to your father in heaven” (Matthew 5:16). This is not the light of our own performance, of our hard work, of our status as good citizens, or even of great church programming. It is the light of Christ as we are together clothed with Christ, as those who have died to our old lives and who are now obligated to others nothing but love.

September 10, 2017