Commentary on Romans 13:8-14

It is perhaps a conventional American aspiration to be debt-free in every way, because it marks autonomy and self-sufficiency.

A measure of self-respect may come from living according to the twin principles, “owe nothing to anyone,” and “no one owes me anything.” The catchy line “don’t believe the world owes you a living,” quipped by American clergyman and humorist Robert Jones Burdette (1844-1914), has become axiomatic.

Pop culture even replicates the idea. A scene in the movie Rocky shows an argument between Rocky Balboa and Paulie, his friend and brother-in-law, in which Rocky says, “Come on, you act like everybody owes you a livin’ … Nobody owes nobody nothin’. You owe yourself.” But the apostle Paul espouses a different idea for the Christian community in Romans 13:8-14. There, he calls believers to live according to the principle that one obligation can never be settled: the debt of love.

Paul unfolds his gospel of grace in chapters 1-11. In light of that gospel, he calls his audience to offer their bodies “as a living sacrifice” (12:1-2). The rest of chapters 12-13 begin to show the practical outworking of sacrificial living. Paul’s audience can begin to see what it means to “be transformed by the renewing of [their] minds” so as to “discern what is the will of God” (12:2).

It means thinking and acting in a way so as not to please oneself but others (verses 3-8), and it means making one’s love for others genuine (verses 9-21). In other words, this sacrifice is not accomplished independently, but in and through community.

Paul addresses the Christian community’s relationship to governing authorities (13:1-7), recalling his appeal, “If it is possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (12:18). Now in 13:8-14, he recapitulates the theme of love for others. This sets the tone for the exhortations of chapters 14-15, in which Paul calls stronger and weaker believers to live together in mutual love (14:14).

The catchword “owe” connects 13:7 to 13:8. Paul shifts from addressing obligations to the governing authorities to addressing obligations to one’s neighbor. His audience is to have no outstanding debts except to love one another. The reason for this debt is, “for the one who loves another has fulfilled (pleroo) the law” (verse 8b).

Paul clearly means the Mosaic law, because he lists four of the Ten Commandments: do not commit adultery, do not murder, do not steal, do not covet. It may seem that he contradicts what he went to great lengths to establish earlier in the letter, that through Christ, believers have died to the law to live anew in the Spirit (7:4-6).

Paradoxically, however, believers have died to the law so that the law may be fulfilled in them. Paul’s audience may recall the last time he appealed to a commandment. In 7:7, he explained how sin took advantage of the commandment, “You shall not covet,” to produce covetousness.

Nevertheless, he says, the law itself is not equated with sin, but is “holy and righteous and good.” Rather, sin is what makes the commandments deadly (7:11). The solution, then, is not to dispose of the law altogether, but to deal with sin.

God sent Jesus to break the relentless hold of sin and death over human beings, “in order that the requirement of the law might be fulfilled (pleroo) in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit” (Romans 8:4; see 13:8b). For those who are in Christ and living by the Spirit, Paul can now say that, “You shall not covet,” with the other community-oriented commands listed, is constitutive of the law of love (13:11-14).

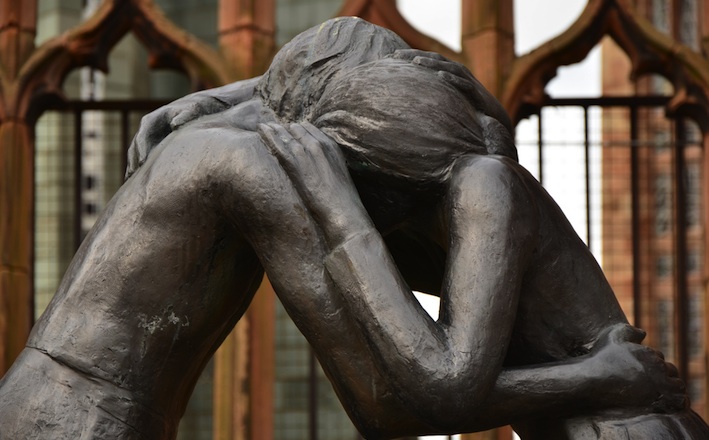

This is what Jesus said: All the law and the prophets hang on two commands, love God and love your neighbor (Matthew 22:34-30; see also John 13:34-35). It is also what Jesus himself did. In light of an instance of failure to love neighbor (chapter 14), Paul presents Christ himself as the example to follow: “Let each of us please his neighbor for his good, to build him up. For Christ did not please himself, but as it is written, ‘The reproaches of those who reproached you fell on me’” (15:2-3). Jesus acted for the sake of others, making his love for others genuine at the cross.

In 13:11-14, Paul shifts the vision of his audience to see the command to love one’s neighbor in light of the future day of salvation (see 8:18-25). He writes of the salvation approaching “us,” highlighting its community orientation. The appeal to awaken from sleep and lay aside the deeds of darkness evokes the appeal not to be conformed to “this world/age” (aion) in 12:1-2.

Paul also writes about this idea elsewhere, explaining that Jesus “gave himself for our sins to deliver us from the present evil age” (aion; Galatians 1:4). Those who are in Christ belong to a new age with new values. Actually, these are old values (“Love your neighbor as yourself,” Leviticus 19:18) that have been vivified by Christ through the Spirit (see also Galatians 5).

Paul uses typical eschatological language, building a contrast between this age and the new age by opposing darkness and light, night and day. Since believers belong to the age of light and day, they are to put on the armor of light (verse 12). This is synonymous with putting on the Lord Jesus Christ (verse 14). In the context, to put on Christ is to imitate him in loving one’s neighbor through self-sacrificial service. The love that believers express is a weapon against the darkness and the flesh as the community moves together towards the day of salvation.

The debt of love can never be settled because we grow up into the salvation that is ours in Christ by loving our neighbor through the work of the Spirit. The working out of our salvation is a community undertaking, making impossible for us to live as free agents.

September 7, 2014