Commentary on Exodus 12:1-14

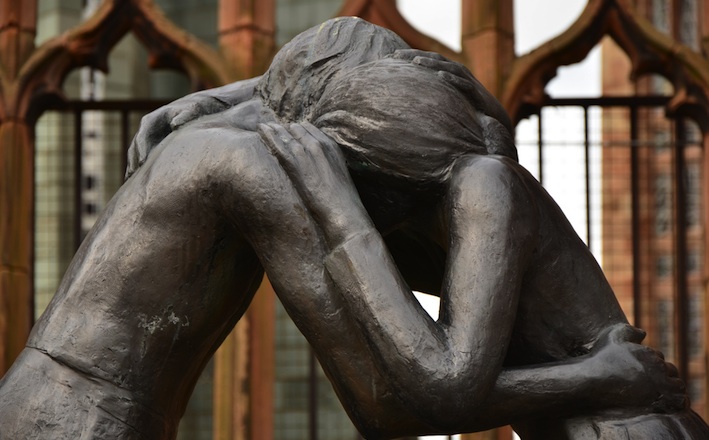

Wherever you live right now, it is probably Egypt in some way or another.

In other words, there is a better land, a better world that could be established were you not stuck in Egypt. But the only way to get to that better land — by no means simply relegated to the geographic location of the soles of our feet — is by joining together and marching toward it.1 The Exodus event speaks deeply to the relocation and reformation of our souls as being part and parcel to the work of bringing God’s Kingdom revolution into the here and now.

This is what the Exodus teaches every generation of its readers. This is why Exodus imagery and imagination has played a crucial role in revolutions, from the Christ revolution to the civil rights revolutions in the United States and beyond.

Over the next couple of weeks in the lectionary, preachers can explore the importance of the Exodus narrative for Israel, as well as for the early church. And of course preachers may want to explore implications of this theological event for those awaiting revolution and liberation in our world today.

A Festival Established

This week’s passage is not the actual Passover event itself, though it has been alluded to in Exodus 11. The event will then come to pass following the establishment of the annual commemoration, or “perpetual ordinance” (Exodus 12:14) in verses 28 and following. After the event, we get even more guidelines surrounding the establishment of the Passover festival. Why all the liturgical doctrine? The voice of a liturgical theologian drives the telling of this event and so establishes the need to retell the paradigmatic story of God’s successful confrontation with a particular tyranny at a particular time, for in all particular times we will always come face to face with novel forms of tyranny.2

The Exodus event itself is the centering narrative of the Hebrew Bible.3 Perhaps we could even say it is akin to the Cross/Resurrection event in the New Testament. To call Yahweh “Deliverer” is to make a confession.4 It is to trust that the One who delivered Israel from oppression and tyranny will do so again. You see this central event throughout the psalms as well as in the theology of the prophets. Jesus of course leans into this core event in the Gospels. The theological good news out of this event is that whenever God’s people cry out under the burden of oppression, liberation will come about.

One last thing about this festival: note that it is established without need of a priest or ordained official religious leader. Rather, it is established as a family celebration, rooted in the home. How might it serve us to think of revolution starting this way?

The Process of Revolution

Although the Passover is the first victory over the tyrant, Pharaoh, it is by no means the final victory. The Exodus narrative leads us to the wilderness which leads us to Sinai and the establishment of covenant with God that will then lead to a good and proper rooting of the people in Canaan, land of milk and honey. Generations come and go in this period of revolution. Moses, the leader of the revolution, will not live to see the construction in Canaan take place. Revolution takes time.

One can see a process of revolution take shape in the book and its three primary locations:5

- Egypt: the place of oppression and struggle for liberation

- Wilderness: the place of perils, counterrevolutions stirring up in the still maturing people who are liberated but not yet consolidated

- Canaan: the place where construction of a new society can now occur

But of course, the story of Israel — of God’s people seeking to live and do right by God in creation — does not end there. We are forgetful creatures. Hence the need for a perpetual ordinance. In Christian tradition, that perpetual ordinance is communion. As one scholar put it, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. And if the oppression is repeated, so must the liberation be.”6

Jesus, our Passover Lamb

Some traditions of the Christian church emphasize the parallel between this Passover event and the meaning of Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross during Passover festivities years later. Just as the blood of the unblemished lambs, spread on the door posts and lintels of Israel’s homes, allowed for the first born to be spared the tenth and final plague, so too does the blood of Christ shed on the cross help those who believe in him to pass through the plague of sin and into eternal covenant life with God.

What is the theological connection for those who do not ascribe to atonement theologies? Perhaps the good news of the cross in this framework is the revelation of a God who desires covenant not just with Israel but with all of humankind. Perhaps it is the good news of a God who does not only hear and respond to the cries of one tribe without concern for the cries of another.

Preaching Against the Text

Related then to the good news just mentioned, some preachers may feel the need to preach against this text. Do we affirm that God chooses to harden the hearts of some people (Pharaoh, Exodus 7:3; 10:1; 11:9), resulting in the ordained slaughter of those who had no say in the matter (the first born of Egypt)? In a globalized world, how might we imagine a congregant or neighbor of Egyptian descent overhearing this text? These are the theological landmines that are hidden in this very important text.

Notes:

1. Michael Walzer. Exodus and Revolution. (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1985), 149.

2. Walter Brueggemann. An Introduction to the Old Testament: The Canon and Christian Imagination (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), 54.

3. George V. Pixley. On Exodus: A Liberation Perspective. (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1987), xiii.

4. Gerhard von Rad. Old Testament Theology Volume 1 (New York: Harper & Row, publishers, 1962), 176.

5, Pixley, 81.

6. Walzer, 115.

September 10, 2017