Commentary on Ephesians 2:11-22

Circumcision, uncircumcision, and blood. These words all seem very abstract and not part of our cultural fabric.

The blood of Jesus is an important theological concept; but the phrase weirds people out. Talking about circumcision does not immediately imply something about one’s status as part of the people of God. People think hospital and current debates about whether it’s child abuse. The words don’t connect with the vast seas of non-seminary grads (and sometimes even for seminary grads) as we often assume it will. People are either confused by such churchy words, or they fit the words into oversimplified categories of Christian theology. If we are to communicate this passage effectively, we need to get past the words.

Ephesians 2:11-22 in Context

Rhetorically, Ephesians 2 lays very important groundwork for the rest of the letter. It’s helpful to see the argument in terms of concentric circles. The outer circle in 2:1-10 communicates God’s cosmic transformation of humanity from being dead in sin to alive in Christ. The inner circle in 2:11-22 begins with a “therefore” (dio), suggesting that everything said issues from 2:1-10. Here Paul1 focuses on the reconciliation of Jew and Gentile, which falls within God’s bigger move of reconciling humanity from sin and death to life. This social, on-the-ground-relational transformation cannot be divorced from the greater cosmic move of transferring humanity from the house of the old aeon to the new house under the lordship of Jesus Christ. God’s reconciliation does not stop with me and my own sinfulness; it aims to resurrect humanity from the palpable widespread systemic brokenness of a world caught under sin and death.

Uncircumcision and Circumcision

Verses 11-12 focus on Gentiles who had been excluded and separated. They are the “uncircumcision.” It is not that Gentiles were “not saved” — not on the train to heaven but rather on the highway to hell. The writer describes their situation as “apart from Christ, separated from the commonwealth of Israel, and foreigners to the covenants of the promise, not having hope and godless in the world.”

These verses provide opportunity to go in two directions. First, they provide a doorway to reorient the idea of God’s salvation. Being saved is not just “getting a ticket out of hell,” or positively put, assurance of heaven. It is a movement from one sphere of life to another. These verses remind us: salvation involves more than forgiveness of the individual sinful self; it is the integration into God’s work of redemption and reconciliation, which is strongly implied in the following verses (see also 2 Corinthians 5).

From the perspective of the author, humanity outside of God’s reconciliation exists as hopeless wanderers. It’s not that humanity apart from God has no identity or home. Humanity apart from God’s mission would not see themselves this way. But human identity outside of God’s working of redemption is about as lasting as the fog in the San Francisco bay. Sure, it’s thick and dense and a force to be reckoned with; but it will pass, revealing it was only a mist with no substance. It’s not that God has called humanity from nothingness; God has called humanity from the illusion that our stubborn insistence that we and our manufactured ways can actually bring into actualization our full identity as those made in the image of God.

Second, and related, these verses provide an opportunity to reorient hearers in our congregations to the importance of God’s historic people Israel and their story in the Old Testament — the “circumcision.” God’s salvation cannot properly be understood apart from the overarching trajectory of the unfolding mission of God through the people of Israel. And this is more than just finding the moral of the story in the various stories of Old Testament characters. It’s common to see Israel as incomplete apart from Christ, to minimize their place, seeing them as a “waiting room people,” to ask “what’s the moral of the story of David and Goliath?” Israel’s story is more significant than this. Scripture’s witness sets Israel as witnesses to God’s creational intentions in the world, an alternative people who witness to the promises of God to restore, and the ones through whom God would accomplish this. In spite of their humanity and struggles with God, their story remains the central witness to God and God’s ways, as well as to God’s faithfulness to not only redeem humanity, but to do so through the people Israel.

The Two Have Become One

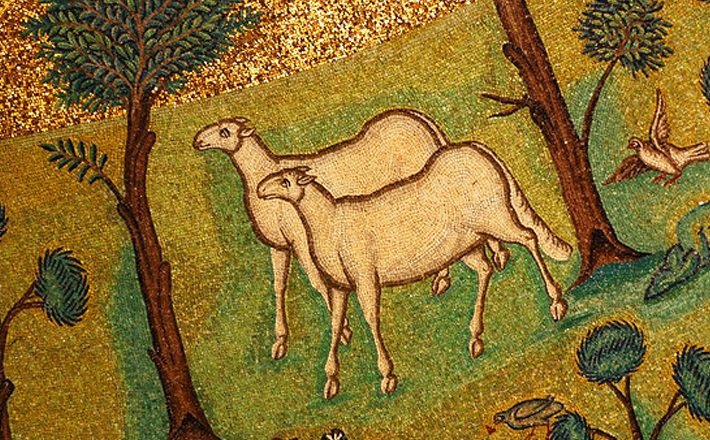

The circumcision and the uncircumcision are two separate groups within humanity according to our author. One group was considered outsiders, the other insiders with regard to covenant with God (and it was not only that Jews saw Gentiles as outsiders; from the perspective of Gentile life and religiosity, Jews were equally ignorant of God as defined by their history and tradition). This separation between the two groups was not limited to theological disposition — to “belief”; it played out in very real ways in terms of human social relations. While it would be incorrect to say these groups of people had no interaction, it is important to understand that they did not sit at the same table together; they were not interested in sharing life. They were opposed.

This passage trumpets the good news that God has brought uncircumcision and circumcision together. One radical element of this message is that God’s unification of the two groups does not mean “uniformity.” One group does not fall under the power of the more dominant group. Rather, Paul says that God in Christ has made one humanity of the two. Gentiles do not become Jews; Jews do not become Gentiles. Rather, both Jews and Gentiles become united in Christ as Jew and Gentile. The uncircumcision are welcomed into the story of God played out through the people of the circumcision, to play their own part in the continuing story of redemption.

The point is that God’s reconciliation and transformation of humanity finds expression in a unity marked by welcoming and hospitality. Consider areas of divisiveness within the church, or even within culture. We even in the church should not presume that those outsiders need to become like us. The church should be a light that paves the way by welcoming both Jew and Gentile and uniting them into God’s mission in Christ (consider “conservative” and “liberal” [as useless as these phrases are, they remain very much in the vernacular of most churchgoers]; homosexual and heterosexual — not simply the people so identified, but even those who hold positions on both sides; American and Muslim; the list goes on).

Blood

This reconciliation comes through the blood of Christ. Behind this statement lies the upside-down idea that such uniting of humanity was won not through the blood of conquest and victory, but through (in the eyes of the world still enslaved to the spirit of the air) the blood of defeat. Where the unity sought in the Roman world came through conquest and uniformity to Rome’s ways, the victory of God comes so differently that it is unrecognizable to the world. “The powers’ triumph over Christ was their own defeat.”2 It’s not that Christ defeated them, it’s that in their defeat of Christ, they show themselves still remaining under the ways that lead to death and have always led to death since Genesis 4. Through death to the ways that lead to death — in blood — God in Christ has brought an end to those ways and raised up a people who die with Christ to witness to reconciliation and unity in Christ.

Notes:

1 I am unpersuaded by arguments against Pauline authorship of Ephesians.

2 Timothy Gombis, The Drama of Ephesians: Participating in the Triumph of God (Downers Grove: IVP Academic) 88.

July 19, 2015