Commentary on John 13:1-17, 31b-35

This is not only a story about what Jesus knew (that “his hour had come”), it is also—and, perhaps, more importantly—about Jesus’ love (13:1). Did Jesus’ knowledge or his love drive his action? Wasn’t it both? Despite the presence (and action) of “love,” the first part of the lectionary passage is framed by “knowledge” (see 13:1 and 13:7).

The fourth Gospel not only opens with the Passover in the air, it also opens with Jesus’ knowledge of his forthcoming death (13:1). In addition to knowing that “his hour had come,” Jesus also knows that he will return to his “Father” (13:1, 3) and that God had “given all things” to him (13:3). Juxtaposed with the description of Jesus—as a person of knowledge and love—stands Judas whom the devil has influenced (13:2). Just as Judas was prominent in the earlier “foot-washing” scene (12:1-8), so his upcoming betrayal lingers in the background of this scene.

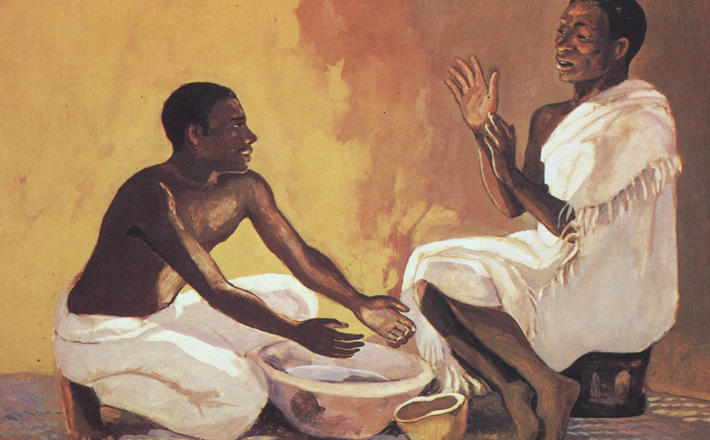

Jesus’ knowledge was not shared by others—including Peter (13:7)—but his self-awareness allowed him to commit to the subservient gesture of washing the feet of his disciples. This scene may serve as a narrative example of the Philippians 2 hymn that Paul preserved (Philippians 2:6-7): “who, though he was in the form of God … emptied himself, taking the form of a slave … ” Striking is how the fourth Gospel emphasizes Jesus’ “knowledge” about himself as a precursor to what he was about to do—perform the act of an enslaved person (13:5).

Indeed, the enslaved commonly performed the service of washing feet whenever guests arrived at their masters’ homes. Since their own “master” (kurios) was initiating this practice, Christ-followers should repeat Jesus’ “slave” performance of foot-washing since “slaves are not greater than their master” (13:16). How representative this practice was in the early church is unclear, since there is little evidence for the practice elsewhere in the early Christian (New Testament) documents. Those “slaves” who perform this servile activity on behalf of others would be considered “friends” because “the slave,” on the other hand, “does not know what the master is doing” (John 15:15).

The interruption of religious practices within the community—as Peter does in this scene—is often a time to think more deeply about the symbolic practices of the community. On the one hand, it is easy to blame the interrupter, but sometimes the disruption originates from a deep inquisitive spirit, a longing desire to know more, a practical wisdom to assist the faithful, a desire to be relevant, and a longing for something more contemporary. So, we should not be so harsh on Peter. As the Gospel of John depicts, Peter apparently raised his concern from an attentive acknowledgment of his social position. He knew that the activity Jesus performed, the enslaved generally performed. Furthermore, if nothing else, he knew that he should perform this act on Jesus not the other way around. Nonetheless, he apparently misunderstood the moment. The reality in which he found himself was one in which Jesus—knowingly and lovingly—acted to express that love for his close followers. And, Peter did not quite have all of the necessary information to make his case.

On the other hand, once Peter determines how much he has misunderstood, he moves to the other extreme—“wash my whole body, Lord!” He wanted to make the symbolic practice something it was not meant to be. He wanted to use this practice for another function, another objective, another way of being in the world, making another kind of statement. That is, he wanted to make a public (even political!) claim with this symbolic practice. He didn’t want the practice withheld; he wanted Jesus to put a more significant, public mark upon him that Jesus had not intended to do. Sometimes the rituals of the church—When should baptism occur? Who can receive the Eucharist?—are used for other purposes, that is, to exclude and isolate rather than to include and invite into community. Jesus’ response is simple but direct: “You do not know now what I am doing, but later you will understand” (13:7).

As a side-note, the fourth Gospel did not portray Peter as the “ideal” disciple; rather, the “beloved” one is depicted in that way (13:23-24; 21:20-22), even though Peter drives the narrative, the storyline, which allows the audience to hear their questions in his voice. Also, key information from John 13 is excluded from the lectionary selection, Peter’s further misunderstanding about the meaning of the symbolic washing (13:8-11), Jesus’s insistence that the practice (of foot-washing?) continue (13:12-17), and, finally, a description of Satan’s “entrance” into the betrayer’s heart (13:18-30).

Perhaps, most crucial—as we return to 13:31 in the lectionary selection—is information for understanding the meaning of “glorification” of the “Son of Man,” especially since the death (=glorification) is still forthcoming in John. In the missing section, once Judas receives the bread, Satan “entered into him” (13:27) in order to initiate the betrayal, which will lead to Jesus’ death—and, in the parlance of the fourth Gospel, the Son of Man’s glorification (in other words, death and ascension to his original position next to God—12:16, 23, 28; 17:1, 4, 24).

The larger lectionary selection not only relays what Jesus knew, but also emphasizes Jesus’ love (13:1 and 13:35). Jesus’ knowledge clearly drives his action, but he expects love to drive the action of his followers: “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (13:35). Within the confines of chapter 13, the experience of love is expressed most prominently in the practice of washing the feet of others (13:14-15).

It is not only about what Christ-followers know, but what Christ-followers love. Or, to put it another way, it is not about what you do with the knowledge you have, but what you do with the love you have. If nothing else, Jesus’ symbolic practice ought to remind Christ-followers to link the sacred traditions of the church to love and vice versa. The sacred practices—such as physically washing another person’s feet—is not only humbling but also intimate, restorative, and symbolic of our expression of love for others within the community, and, perhaps, moving beyond the fourth Gospel, this practice could symbolize love for those outside the community.

April 14, 2022