Commentary on Genesis 29:15-28

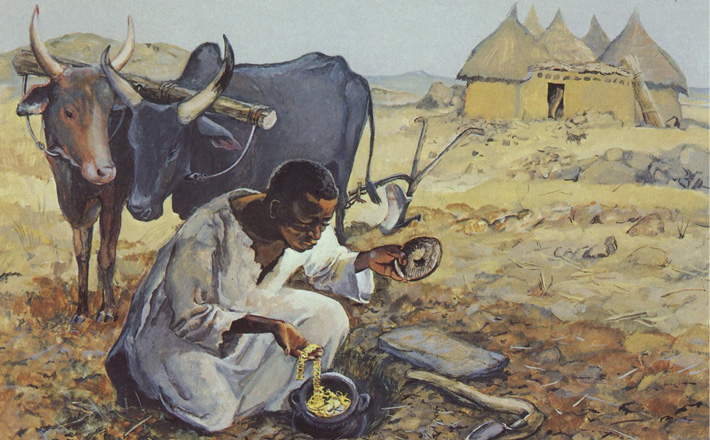

The story of Abraham’s family continues this week with Jacob.

After fooling his father taking his older brother’s birthright, he decided to get out of town and head to the land of his ancestors. During his last night in Canaan, he dreamed of a blessing from God on his offspring (last week’s Alternate 1st Reading in the Revised Common Lectionary). This week, he arrives in “the land of the people of the east,” meets Rachel, and is taken to his uncle, Laban.

The focus text for this week is Jacob’s deal with Laban for the hand of Rachel. However, Laban tricks Jacob and gives him Leah instead. One can ponder how Jacob did not notice his bride was a different woman, but the text does not speculate how Laban pulled off the switch. Nor does it indicate how Leah felt as Jacob is tricked and then makes another deal to work an additional seven years for her younger sister, Rachel. We also do not know what Leah and Rachel thought all of this. The women are completely silent in the narrative.

If we only consider the main characters, Jacob and Laban, one could argue that Jacob gets what he deserves. He cheated his brother out of his birthright and then runs away only to be cheated by his uncle. This family is not living up to the high hopes God ordained in promises given to Abraham. Abraham allowed Sarah to be given to other men twice in his narrative, followed by Rebecca and Jacob’s treachery, and finally Laban in the marriage of Jacob. The Gospel is hard to find here as we learn about this family of promise because of their history.

But when we consider the women, the news gets worse. First as noted above, the women do not speak. They are part of the deal. They are property. They are forced to marry the same man and compete for his favor in the birthing of the children. This in and of itself would be hard enough. But there is another difficult chapter for these women. Genesis 29:17 reads “Leah’s eyes were lovely, and Rachel was graceful and beautiful (NRSV).” The NIV follows the older tradition and states “Leah had weak eyes, but Rachel had a lovely figure and was beautiful.” The Hebrew word describing Leah’s eyes is unclear, and both meanings are possible. The meaning of the sentence is further complicated with choice of the conjunction “but” (NIV; other translations use “and”). This choice of words sets Rachel as a direct contrast to her older sister. The final nail is the choice of “beautiful figure” for Rachel (Hebrew is “beautiful appearance”). As a child, I was told Rachel was beautiful, and Leah was plain or even ugly. The text, of course, does not say this overtly. But poor Leah has been maligned as the lesser sister for centuries (see the Michelangelo statues of the two in the San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome). The message I received as a child was that the beautiful sister was favored and the “ugly” one will only be married if the man is tricked into it. So again, Gospel is hard to find here because God is hard to find. Jacob worships God and he is faithful throughout his life, but God does not show up and fix what this family has broken. Nor does God intercede in sexist views of the two sisters. This story displays both overt sin in the acts of Jacob and Laban and corporate sin in the sexism that not only makes women property but then judges them on their appearance.

It is easy to sit in judgment of Jacob and Laban. We can sit comfortably on a Sunday morning and condemn their actions and their culture and thank God we have evolved. But that would mean we miss the point of the narrative completely. They are not “them.” They are us. We are far from perfect. Families are messy and often broken. We hurt each other intentionally and unintentionally. We act in our own best interest and against the greater good of others. We forget to ask those with less power about decisions that impact their lives. To look on this family is to look straight into human brokenness. To look on the culture is to hold up a mirror to our world that still judges individuals on their appearance and treats women as less than men.

So, is there a Gospel message this week? Yes, it is the same one found in Esther, a book that never mentions God. The Bible tells the story of the family of Abraham and Sarah, warts and all. It is not cleaned up to impress the neighbors or provide unobtainable role models for moral living. They are faithful and sinful. They are blessed by God and cursed by their actions. Their culture is on display in this text, and it has a good dose of corporate sin in its sexism and treatment of those with less power.

Psalm 105:1-11 places this story in the proper perspective. “O give thanks to the Lord, call on his name, make known his deeds among the peoples” (Psalm 105:1); “He is mindful of his covenant forever, the word that he commanded, for a thousand generations, the covenant he made with Abraham, his sworn promise to Isaac, which he confirmed to Jacob as a statute, to Israel as an everlasting covenant” (Psalm 105:8-9). God is praised for God’s faithful and everlasting covenant to the very people in this narrative. Gospel is present because God keeps God’s promises to a sinful humanity. God is faithful when we are busy managing our lives. God is faithful even when God is not overtly part of the narrative. God loves the broken families of the world. God loves so much God will send his son to “the sons of Israel” and by extension, to us.

July 30, 2017