Commentary on Psalm 119:129-136

There is an ancient and venerable teaching in the church on the word of God.

It has three forms. The first in importance (though not in time) is the word of God enfleshed. Protestants tend to forget this, thinking first of the word of God in the Bible. But that is the second and derivative form of the word of God. Ours is a biblical faith, but it is only insofar as the bible bears witness to the word in Mary’s womb. Third, and this is most staggering of all, the word of God is the word of the preacher.

Now sit under the weight of that for a moment. We may think we just dashed off a Saturday night special, caught between too much to do and not enough creativity. We’re keenly aware of the folks who just barely got there that morning who wonder why they did, of those staying as far away as possible, and those whom God adores but who would never come near the door of the church. It may feel limp or even dead as it leaves our lips. But that’s the very word of God — the same word fleshed in Jesus and attested in scripture. It always looks and feels foolish. Actually it’s the hinge of history and the heart of the world.

Psalm 119 luxuriates in the word, the decrees, the ordinances, and the law of God. It is not a psalm of half measures or cool reserve. The psalmist longs for God like a ferociously thirsty dog pants for water — slobber everywhere, heavy breathing, sucking the bowl dry (verse 131). The psalmist laments other people’s sins, and of course also her own (verse 136). Sin is not an occasion for blame or shame or gossip, but for tears. They are, as the Orthodox Church has long taught, like a second baptism, a cleansing — there’s a reason you feel better after a good cry. The psalmist asks for God’s face to shine on her the way Aaron asks for God’s face to shine on those whom he blesses in the famous passage Numbers 6:22-27. The shining face of God is what calls all things from non-existence to existence, from selfish sin to abundant and self-giving life.

The powerful images keep rolling over us readers and pray-ers. As a preaching professor I teach students to choose one image and let it carry the freight of the sermon. Wise teachers like Paul Scott Wilson have shown that the human ears can only hear one image at a time.1 Pile them up and they become a train wreck. But scripture doesn’t get the memo. They rain down in quick succession. “Unfold” your word God — when we teach, God is actually unpacking treasures, laying them out for display, delighting in the onlookers’ oohs and aahs (verse 130). “Turn” to us the psalmist asks (verse 132), in perhaps her boldest request. The desire is for God’s full presence, the very light of God’s face.

God had made clear to Moses that none of us could see God’s face. Moses seeing God’s backside makes his face shine so brightly the people demand a cover — don’t irradiate us God, we can’t stand the full voltage of your presence.2 And yet the psalmist here asks for full blast dosage. The Sinai covenant, in one way, isn’t forefronted in Psalm 119. In another way, it is implicitly present throughout this section, verses 129-136. The details of the Torah are not spelled out in this massive psalm — which had ink enough to spare if it wanted to go into the details of the law. Rather the law is delighted in.

This is the God whose women celebrated a triumph at the side of the Sea (Exodus 15), the God who liberates from slavery (verses 133-134). Too much of our faith seems dutiful, joyless, desiccated and anemic. Psalm 119 shows us a faith that is about delight, with blood and water pumping through to overflowing, full of saliva and tears, shining faces and redeemed slaves.

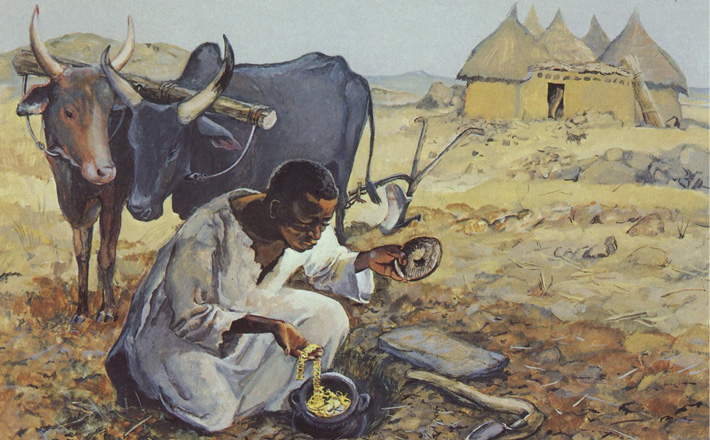

The psalm portion concludes with several mentions of slavery. We know who God is — the one who sets people free. This is not about long past history — activists have shown that tens of millions of people live in slavery in our world today, bound by an economic system that prizes low prices above all and petty tyrants who physically restrain and economically shackle. It often looks like slaveholders have nothing to fear. If there is no God, that is. God, Robert Jenson says, is whoever raised Israel from Egypt and Jesus from the dead. You know the presence of this God by broken shackles and rolled away stones. And you know this God’s servants by the wrists and ankles formerly rubbed raw suddenly liberated.

Jon Levenson is one of our finest Hebrew Bible scholars. He wrote an essay on the Exodus some decades ago that quibbled with liberation theology, which was then in an early ascent.3 Exodus is often drawn upon as the key image of liberation. He pointed out that the Lord liberates Israel from slavery to Pharaoh not in order to make them free, masterless, self-governing. No, God liberates Israel to make them slaves…to Yahweh. We have to serve somebody, as Bob Dylan once crooned. The Lord who asks us to serve and will not make us do so against our will has a yoke that is easy and a burden that is light. Jesus learned such language from places like Psalm 119, which describes the law in similar terms. Sure, it’s a burden, it’s not convenient, it’s not what we would have designed if we were God.

But it is the lightest yoke there is.

Notes:

1. The Four Pages of a Sermon: A Guide to Biblical Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon, 1999).

2. For real — look it up, Exodus 33:18-34:9.

3. Jon Levenson The Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament, and Historical Criticism: Jews and Christians in Biblical Studies (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1993).

July 30, 2017