Commentary on Luke 10:25-37

In the Lukan context, the parable of the Good Samaritan is prompted by a dialogue between Jesus and a lawyer.

“A certain lawyer stood up to test him, saying, ‘Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?’” (Luke 10:25). This question is repeated verbatim near the end of the travel narrative on the lips of the rich ruler (18:18). Here Jesus responds with his own questions. “He said to him, ‘What has been written in the Law? How do you read it?’” (10:26). The lawyer takes the bait by quoting from the Law (Deuteronomy 6:5; Leviticus 19:18) as Jesus had directed him: “He responded and said, ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind; and (love) your neighbor as yourself’” (10:27). The response is in the form of a rhetorical exemplum, that is, the citation as authoritative of something done or said in the past.1 Jesus affirms his answer, noting that observing these commandments will lead to the life the lawyer seeks: “Then he said to him, ‘You have answered correctly. Do this and you will live’” (10:28). But now the lawyer has a question of his own: But he, since he wanted to justify himself, said to Jesus, ‘Who is my neighbor?’” (10:29). Questions of the “who” and “how” of justification will recur later in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9-14). Jesus responds to the question, not with another question, but with the story of the Good Samaritan (10:30-35).

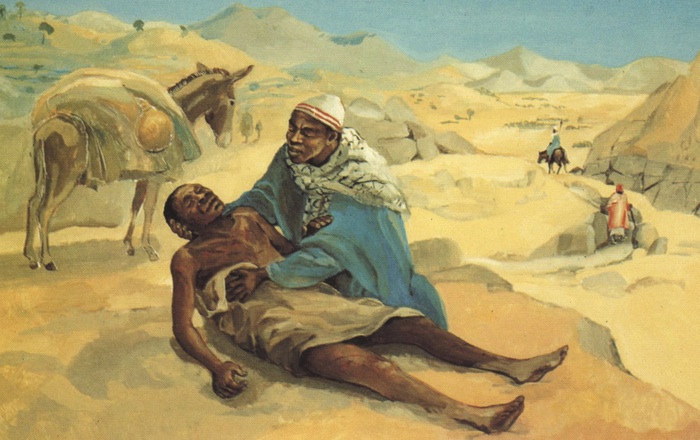

The meaning of the parable in a larger Greco-Roman context is illuminated by relating the Samaritan’s act of compassion with the virtue of philanthropy as practiced in the ancient world and as it would have been understood by an ancient audience. Of course, that such virtuous philanthropy is exhibited by a Samaritan and not the pious Jewish layperson would have come as a surprise to the lawyer listening to the story in Luke (and no doubt to Jesus’ Jewish audience).

What more can be said regarding the parable within its Lukan framework? Despite the fact that modern scholarship has been generally negative toward a Christological reading2, it is worth revisiting the argument. The term esplagnisthe (“he had compassion”) occurs three times in all of Luke; in the other two instances, only God’s agent, Jesus (Luke 7:13) and a figure for God, the father of the Prodigal (Luke 15:20) show compassion. In other words, “showing compassion” in the Lukan narrative is a divine prerogative and a divine action.3 Here is our first clue in the text of Luke itself that the Good Samaritan, when he shows compassion on the man in the ditch, is functioning figuratively as God’s agent.

This interpretation gains momentum when one considers the Lukan frame within which the parable is set. At the conclusion of the parable, Jesus asks, “Which of these three seems to you to have been a neighbor of the one who fell into (the hands of) the robbers?” (Luke 10:36). The lawyer responds by saying, “The one who had mercy on him” (10:37). This comment is usually understood to show the lawyer’s reluctance to even utter the word, “Samaritan.”4 Without denying this claim, the response also has the effect of creating an interpretive gloss on the Samaritan’s action. The Samaritan’s act of compassion is construed by the lawyer as the dynamic equivalent of “showing mercy.” This interpretation is evidently accepted by Jesus and the narrator, since neither corrects nor contradicts the lawyer. This interpretation would seem crucial for getting at Luke’s understanding of the Samaritan’s action, and through that action to the Samaritan’s “identity.” As with “compassion,” virtually every instance of “mercy” in Luke is associated with acts of God or God’s agent, Jesus (Luke 1:47-50, 54, 72, 78; 17:13; 18:38-39; the only exception is when Father Abraham refuses to show the rich man “mercy” [16:24], an exception which ultimately proves the rule that in Luke’s Gospel only God and Jesus show mercy). Within the immediate context of Luke’s Gospel, the Good Samaritan, who “shows compassion” and “does mercy,” functions as a “Christ” figure who ultimately acts as God’s agent.5

The story ends with Jesus admonishing the lawyer: “Go and do likewise yourself!” (10:37), causing many interpreters to label the parable as an “example story.” Certainly this is an important aspect of the parable within its Lukan context, but to label the Parable of the Good Samaritan an “example story,” as though the story were itself devoid of a Christological or theological referent, is to miss a significant point of the parable. The parable, in its narrative context, does not primarily focus on the perspective of the man in the ditch (contrary to popular interpretation). Rather, Jesus’ admonition to the lawyer demands that the primary perspective be that of the Good Samaritan, whose example the lawyer is admonished to follow. The example is here enlivened by the fact that the example of the Good Samaritan’s compassion and mercy is, as the text of Luke affirms, the example of none other than God and God’s agent, Jesus. Thus, we have in its literary context a call by Jesus to imitate the compassionate Samaritan and in so doing to imitate the compassion of Jesus himself. Ethical admonition is grounded in a Christological basis.

For the Lukan Jesus to depict himself as a “compassionate Samaritan” has profound implications. In the immediate context of Luke 9-10, it is to identify with the group upon whom James and John had just offered to call down consuming fire from heaven (Luke 9:51-56), an act certainly understandable to those familiar with Jewish/Samaritan hostilities. Such scandalous identification is not unknown to Luke’s Jesus; rather, it fits in with the generally acknowledged pattern of reversal in Luke’s Gospel, where the world is turned upside down. Furthermore, the radical claims of the parable of the Good Samaritan are not avoided when one excludes Jesus as the referent of the parable, since Jesus calls the lawyer to “act like a Samaritan.” Why should Jesus, a Jew, expect something of a Jewish lawyer that he himself is not prepared to expect of himself? It is in the very offense of the image of the Samaritan as a Christ figure that the parable has its evocative power in its fullest sense.

Material adapted from Luke. Paideia Commentary Series. Eds. Mikeal C. Parsons, Charles H. Talbert, and Bruce. Longenecker. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic (a division of Baker Publishing Group), 2015. Used by permission.

Notes:

1 compare with Rhetorica ad Herennium 4.49.

2 Evans 1990, 178, states flatly: “The Samaritan is not Jesus!”

3 Menken 1988, 111.

4 on the animosity between Jews and Samaritans, see Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 9.29; m. Qiddusin 4.3; John 4:8-9; Luke 9:54.

5 compare with Origen, Homilias in Lucam 34.9.

July 10, 2016