Commentary on Isaiah 52:13—53:12

The church always reads this marvelous text on Good Friday. 1

Few Old Testament passages have provided preachers with as much theological and imagistic grist for the homiletical mill as this fourth and final poem in the so-called Servant Songs of Second Isaiah (42:1-4; 49:1-6; 50:4-9; 52:13–53:12).

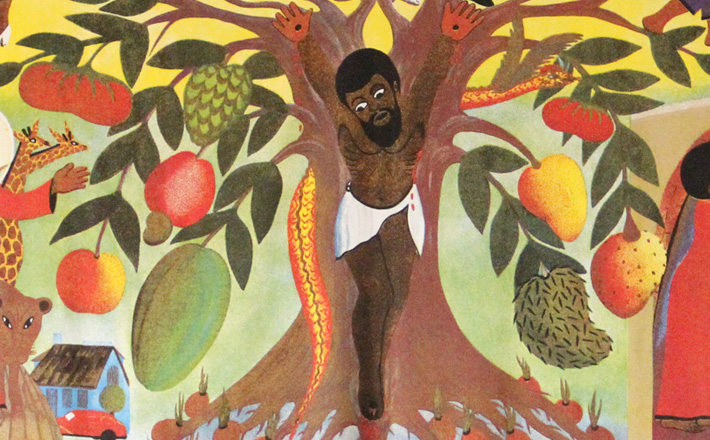

Nevertheless, the passage remains remarkably unyielding with regard to exegetical explanations of who, what, when, and where, not to mention why. Some believe the servant to be a collective figure, usually Israel, whose suffering and dislocation in the exile prove to be redemptive for “the nations.” Others prefer to identify various individuals (Moses, Cyrus, or Second Isaiah, himself, are the top contenders these days) as the servant. The church has naturally seen the suffering, death, and even the resurrection of Jesus Christ poignantly depicted here.

There are problems, however, with all of these attempts to identify the servant. The proponents of an individual identification need to wrestle with the statement that “he shall see his offspring and prolong his days” (53:10), especially in light of the text’s announcement of the servant’s death when it reports “he was cut off from the land of the living,” (53:8). Those identifying the servant with Christ can deal with the death by appeal to the resurrection, but what then of “his offspring”? DaVinci Code, anyone?

The question of the servant’s identity has been debated for centuries without consensus and this will likely continue. Structural observations, however, have contributed greatly to our understanding of the passage, regardless of the servant’s identity. The poem naturally falls into two sections: God’s affirmation of “my servant” opens (A, 52:13-15) and closes (A’, 53:11b-12) the poem framing a “report” (53:1 RSV) of the servant’s mission in the form of a confession (53:1-11a) offered by those for whom the servant suffered, as follows:

A God affirms “my servant” (52:13-15)

B Introduction to the report (53:1)

C Description of the servant’s suffering (53:2-3)

X Reason for the servant’s suffering (53:4-6)

C’ Description of the servant’s suffering (53:7-9)

B’ Conclusion of the report (53:10-11a)

A’ God affirms “my servant” (53:11b-12)

The report itself (53:1-11a) displays a concentric construction. The report opens with wonder as the ones for whom the servant suffered can’t believe what they have heard (B, 53:1). The unbelievable news they have heard is, of course, what we as readers find out in the report’s conclusion (B’, 53:10-11a), namely that “it was the will of the LORD to crush him.” Who’d a thunk it? Or, as our text puts it, “to whom has the arm of the LORD been revealed?”

Their bifurcated description of the servant’s suffering betrays their earlier conviction that this poor loser, disfigured, abused, despised, and rejected was of “no account” (C, 53:2-3). What is worse, he accepted his fate without as much as a peep of protest, “he did not open his mouth.” What a wimp (C’, 53:7-9)!

But in the heart of the passage (X, 53:4-6) these unbelieving, incredulous confessors finally get it. They figure out that while suffering had previously been variously explained as the inevitable consequence of disobedience (e.g. Deuteronomy 28:15) or as a test of faithfulness (e.g. Job 1-2), here suffering, borne willingly, silently, innocently, vicariously, by another in conjunction with the will of God, was depicted as redemptive for others. The ones who had mocked, abused, humiliated, and finally killed the servant are now the ones who confess that he has borne their sin. Their amazement is beautifully presented in the repentant resonance of the Hebrew particles hu (he, him) and nu (we, our) that reverberates throughout this central paragraph:

“He has borne our griefs”

“yet we accounted him struck down by God”

“He was wounded for our transgressions”

If such is the meaning of the report found in 53:1-11a, what then is the function of the divine address that frames the report? When Arthur Hiller, the director of Love Story (the Oscar winning 1970 film, not Erich Segal’s book, upon which the film is based) begins with the final scene in which Oliver mourns the death of his beloved Jennifer, “What can you say about a twenty-five year old girl who died? That she was beautiful and brilliant. That she loved Mozart and Bach. The Beatles. And me,” he dictates how we are to experience his film. We know that she is not going to make it; she is going to die no matter how tragic their pain, how poignant their love. If you miss the first five minutes of the film (potty stops, popcorn purchases, and parsimonious parking places head the list in my family!) you will not see the same film … you will “just know” she’s going to get better and that true love will win out in the end. But that is not the film the director wants you to see.

In a similar way, Second Isaiah frames his depiction of the Gospel in action with the divine speech that lets us, his readers, unlike those for whom the servant suffered, know in advance what is to come. This is the way God has chosen to redeem us. Is it any wonder the church, looking back through the lens of the cross, has found in this heart wrenching poem, a crystal clear portrayal of the events of God’s Good Friday?

Notes:

1 This commentary was first published on the site on April 2, 2010.

April 3, 2015