Commentary on Matthew 5:1-12

When Jesus ascends a mountain and begins to address the crowds (verses 1-2), the reader is expected to make the connection to another teacher (Moses), and another mountain (Sinai).

And soon enough, Jesus will complete that picture by offering instruction in righteousness — the Sermon on the Mount will have plenty to say about what we, as kingdom people, should and should not do.

But that’s not how his famous sermon begins. It begins with a list, but not with a list of “thou shalts” and “thou shalt nots.” Too often, the preacher tries to make the Beatitudes into law. “Be merciful,” the preacher exhorts, “and you will receive mercy.” That may be true at times, but it is not what Jesus is saying here.

The list we find here is in the indicative mood, not the imperative. It is description, not prescription. Jesus is not insisting that we become people who starve to see justice done (verse 6) — I suppose you either do or you don’t. What he is saying is that such people are blessed of God. God looks upon such people with favor. God’s eye is on them; they will be happy in the end. This, says Jesus, is the way things are.

But if the Beatitudes are a description of reality, what world do they describe? Certainly not our own. “Blessed are the meek” (verse 5), says Jesus, but in our world the meek don’t get the land, they get left holding the worthless beads. “Blessed are the merciful” (verse 7), says Jesus, but in our world mourning may be tolerated for a while, but soon we will ask you to pull yourself together and move on. “Blessed are the pure in heart” (verse 8), says Jesus, but in our world such people are dismissed as hopelessly naïve.

“Blessed are the peacemakers” (verse 9) says Jesus, but in our world those who pursue peace risk having their patriotism called into question. To which of these blessings do our national leaders refer when they insist that “God Bless[es] America!” To none of these, for our national creed is one of optimism (not mourning), confidence (not poverty of spirit), and abundance (not hunger or thirst of any kind), and it is in service of such things that we invoke and assume the blessing of God. And so we live by those other beatitudes:

Blessed are the well-educated, for they will get the good jobs.

Blessed are the well-connected, for their aspirations will not go unnoticed.

Blessed are you when you know what you want, and go after it with everything you’ve got, for God helps those who help themselves.

If we are honest, we must admit that the world Jesus asserts as fact, is not the world we have made for ourselves.

And so, for now at least, we do not yet see all these things, “but we do see Jesus” (Hebrews 2:9). Jesus not only declares, but embodies this new world. An old poem promises that a day is coming when every knee will bow and every tongue confess that a crucified man is Lord (Philippians 2:10-11). Everyone will see at last that the one hung upon a tree in shame, the one who in poverty of spirit was forsaken by everyone — even by God in the end, it seemed — the last of the last, is first, is Lord of all. Every tongue will admit that the man of sorrows, the mourner, is comforted at last in the power of resurrection.

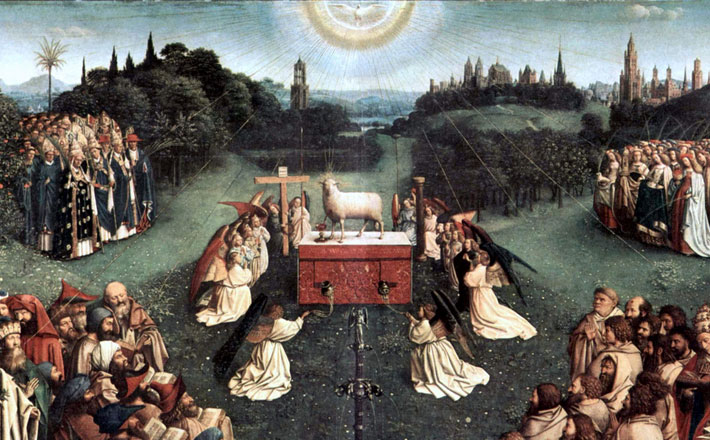

Every tongue will confess that the meek lamb who did not open his mouth before the slaughterers has been granted the earth and everything in it (Matthew 28:18). Every tongue will confess that the one who longed for justice has lived to see justice; that the one who practiced purity of heart is standing in the presence of God; that the great peacemaker is now called the Son of God. On that day every tongue will confess that the one who was persecuted for the sake of righteousness (verse 10) is indeed Blessed of God.

Until that day, the Beatitudes stand as a daring act of protest against the current order. Jesus cannot very well insist that we be poor in spirit, but he can show us how to look upon such people with new eyes, and so gain entrance to a new world. On All Saints Day, the Beatitudes testify that it matters deeply whom we call “saint.”

The Kingdom Jesus proclaimed and embodied is precisely a new way of seeing, a new way of naming, and so a new way of being. The current regime sweeps aside those Jesus declares blessed of God, but we are invited to look again and discern a new reality that is coming into being. When we learn to recognize such people as blessed — to call them saints — we pledge our allegiance to that new world even as we participate in its realization.

November 2, 2014