Commentary on Luke 21:5-19

This is a scene that ought not to have been cut so short.

This is a scene that ought not to have been cut so short. The amputation of the end deforms the scene itself. Read another ten verses, at least. And read a few more on the front end, while you’re at it.

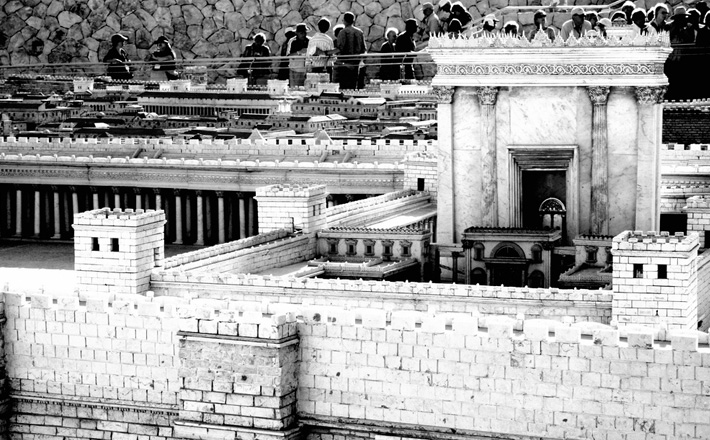

Jesus and his disciples are still in Jerusalem. They are still in the Temple, which is where he has been teaching since the beginning of chapter 20. All of the previous arguments and rhetorical traps have been set in the Temple; these detailed discussions of the most Jewish of issues have been conducted in that most Jewish of places, the Temple, the place where God touched the earth and held it still and safe. Just moments ago the faithful woman, both widowed and impoverished, threw her whole life into the Temple treasury.

And now some of the people with Jesus look up and speak in awe of the beauty of the Temple, the center of the Jewish world. Of course, Luke and Jesus (and every conceivable ancient audience) knew that the beauty of the Temple was a matter fraught with tension and contradiction. The Temple was stunning. The Temple was huge. Paula Fredriksen notes that the outer court could hold 400,000 people, and further notes that, at festival times, it frequently held crowds nearly that large. The Temple was overwhelming, as befits the building that honors the God who alone is God.

And the Temple was beautiful because Herod, that Roman stooge who styled himself as King of the Jews, had spent massive amounts of money making it beautiful. Herod, that vicious and brutal despot known as much for his private slaughter of his family members as for his acts of public largesse, had built up the Temple so that it would rival pagan temples built up by rival rulers. Faithful Jews knew the Temple testified to God’s unique majesty. They also knew that the beautification project was meant to bring glory to Herod, that grandson of converts whom the rabbis refused to acknowledge as Jewish. Nobody that brutal, that barbaric, that pagan, can belong to the family of the faithful.

Jesus’ words, therefore, about the leveling of the Temple, not one stone on another, would have had a double bite. On the one hand, that leveling (even at the hands of Rome) would remove the Herodian blot from the holy city. On the other hand, the Temple was the Temple, and not even Herod’s pagan corruption could change that.

The reason you need to read more verses, and not just stop at verse 19, is that such a truncated text flows from the destruction of a building to geo-political chaos to religious and social rejection (extending even to family-shattering betrayals) to a promise of safety amidst the chaos of martyrdom. And then it stops.

The implication is that the calm individual is the center of the world, that Christian endurance has been the point of Jesus’ whole message.

If you read further, you notice that this sermon, useful and edifying as it is, is swirled back into a larger chaos and that the larger threat is not to Christian endurance but to Jewish survival. Having floated briefly in the eddy of endurance even in the face of intra-family strife, Jesus sweeps that hearer back out into the main stream of this discourse: Jerusalem will be encircled and trampled underfoot by Gentiles, Jews who will flee in terror, and all will see the stability of the universe shaken.

Even in this world-destroying catastrophe, Luke’s Jesus says, God’s faithful people should lift their heads and expect resurrection, redemption, and rescue. It is worth remembering at this point that when Anna saw the infant Jesus in the Temple back at the beginning of the story, she spoke of him to all those who were awaiting the redemption of Jerusalem. Luke’s story requires the audience to imagine all those people whom Anna found as still waiting and expecting a resurrection of faithful hope.

If Jesus’ listeners indeed do lift their heads and look around, they will see, even in the moment of deepest catastrophe, the host of those who have been waiting with them since even before Anna found them and spoke to them. In fact, this chapter ends with that host (in Greek, the laos, a word used in Luke and in the Septuagint to refer to faithful Israel) rising early day after day to listen to Jesus in the Temple.

It is also worth remembering that when Luke’s story was told in this form, the Temple had already been a smoldering ruin, razed to the ground by Roman command, for something like thirty years. The disaster that is forecast has already been seen. This is always the case with proclamations of promise and warning. Any congregation, any group gathered to worship and study will always include people whose worlds have been shattered, whose hopes have been trampled. Some of them might also be old enough to have learned to lift up their heads and look for the promised resurrection even in the midst of the triumph of death. Others will need to be supported while they try just to draw another breath.

This larger scene does not just offer encouragement to heroic endurance. Chapter 21 is a scene that pictures God’s people as always gathering to wait together for resurrection. Sometimes endurance is not enough, not even nearly. When it really matters, only resurrection will do, and in Luke’s story, we wait for resurrection together and in the company of people like old Anna, who has been waiting longer than most of us have been alive.

November 17, 2013